An Intimate Portrait of Mr. W. H.

"The Love that dare not speak its name" in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep, spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art like those of Shakespeare and Michelangelo, and those two letters of mine, such as they are. It is in this century misunderstood, so much misunderstood that it may be described as the "Love that dare not speak its name," and on account of it I am placed where I am now. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an elder and a younger man, when the elder man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so the world does not understand. The world mocks at it and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it.” - Oscar Wilde

After Buck Mulligan’s raucous entrance in “Scylla and Charybdis”, Ulysses’ ninth episode, Stephen Dedalus struggles to regain composure and continue on with his theory of Hamlet. In the midst of this disorder, Mr. Best chimes in to share one of his favorite Shakespeare-inspired texts:

“—The most brilliant of all is that story of Wilde’s, Mr Best said, lifting his brilliant notebook. That Portrait of Mr W. H. where he proves that the sonnets were written by a Willie Hughes, a man all hues.”

“The Portrait of Mr. W.H.” is a short story by Oscar Wilde that lays out a theory about Shakespeare so shocking that it drives two men to their deaths.

Shakespeare theories are not to be trifled with, Stephen take heed.

Like Stephen Dedalus, Wilde’s character, Cyril Graham, leans into the idea that the Bard’s personal life substantially influenced his work. And like Stephen’s theory, Cyril’s theory is not without academic precedent. Willie Hughes is an answer to a longstanding Shakespearean mystery - the identity of the Fair Youth to whom some of Shakespeare’s sonnets are addressed. Shakespeare wrote a boatload of sonnets, but he kept their characters anonymous. It’s assumed Shakespeare himself is their narrator, though not everyone agrees even on this basic fact. Batches of the sonnets are addressed to a mysterious Dark Lady and others to a Fair Youth. Both these groupings of sonnets take on an amorous tone, but the details about the players, their identities, and how sexy they got with Shakespeare must be filled in by the reader. Because there is such a dearth of information about Shakespeare as a man, there are huge gaps in our knowledge about the origin of the sonnets. Despite what is asserted in “Scylla and Charybdis,” the sonnets are actually Shakespeare’s most personal work. As such, some scholars debate whether Shakespeare ever wanted them published at all, or if they were printed without permission by their publisher, Thomas Thorpe. Because of this abundance of mysteries, scholars and enthusiasts alike have concocted several centuries’ worth of fan theories about who they ship with Shakespeare.

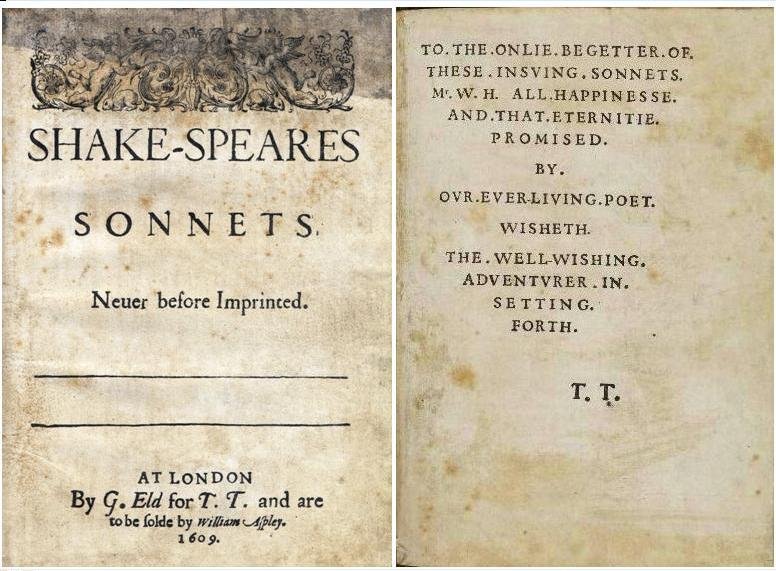

“Mr. W.H.” focuses on a possible identity for the Fair Youth. The theory at the heart of Wilde’s story originated in the 18th century with a scholar called Thomas Tyrwhitt, who found a clue in the dedication of the folio of sonnets published in 1609, which reads in part:

“TO THE ONLIE BEGETTER OF THESE INSUING SONNETS MR. W. H.”

How tantalizing. Could Mr. W.H. be the Fair Youth? William Herbert, the 3rd Earl of Pembroke, is a historical favorite for the role of Fair Youth, and his initials are W.H., so he’s an obvious candidate. Lyster mentions him as such in one passage in “Scylla and Charybdis”:

“Oddly enough he too draws for us an unhappy relation with the dark lady of the sonnets. The favoured rival is William Herbert, earl of Pembroke.”

Another possibility is that W.H. stands for “William Himself,” meaning Shakespeare had nothing to declare but his genius, apparently. Stephen calls this theory to mind in silent response to Best’s admiration of Wilde’s story:

“Or Hughie Wills? Mr William Himself. W. H.: who am I?”

Tyrwhitt proposes a different idea entirely, though. He noticed the following line in Sonnet 20:

“A man in hew all Hews in his controwling”

Shakespeare wove name puns, including puns on his own name Will, into other sonnets and set them off with italics like in this line, so Tyrwhitt speculated this must be a pun, too. “Hews” could be the common surname “Hughes,” so in combination with those other “Will” puns, perhaps Mr. W. H. was a Mr. William Hughes, a man of all hues as Mr. Best says.

Tyrwhitt’s theory didn’t exactly set the world on fire in its day, but it was endorsed by scholar Edmond Malone, which seems to have been enough to keep it in the mix, so much so that sonnet scholar H.E. Rollins complained in the 1940’s that Malone’s endorsement “created a spook harder to drive away than the ghost of Hamlet’s father.” As a result, this 18th century zombie theory winds up in a short story by Wilde and an allusion in Ulysses.

In 1889, Wilde took Tyrwhitt’s theory and added his own twist. In the story, Cyril Graham discovers that Willie Hughes was actually a young actor in Shakespeare’s company who played all the female parts. Cyril serendipitously happens upon a portrait of Willie holding the folio of sonnets with the dedication visible, confirming that Willie is the Fair Youth and the object of Shakespeare’s affections. Sonnet 20, cited by Tyrwhitt, pays particular tribute to the Fair Youth’s beauty and how he is so like a woman without any of a woman’s flaws. It’s not a huge leap to read homoeroticism in this particular sonnet, especially in Wilde’s telling. Apparently Willie H. was a hottie, and Willie S. couldn’t take his eyes off him.

Unfortunately, there is one fatal flaw in both Tyrwhitt’s scholarship and Cyril’s sleuthing: there is absolutely zero evidence of any kind that Willie Hughes ever acted in Shakespeare’s plays or even existed at all. And as with Stephen Dedalus and his own Shakespeare theory, Wilde’s characters disavow their own theory within the story. It’s unclear whether Wilde even believed the Willie Hughes story himself. Lord Alfred Douglas said he did, but the story itself disproves the Willie Hughes story fairly substantially. To top it all off, we don’t even know if Shakespeare wrote the dedication to Mr. W.H. In fact, it’s initialed “T.T.”, or Thomas Thorpe, the publisher.

Before we move forward, I have to get one thing off my chest. Best also has a fatal error in his recollection of “Mr. W.H.”: that the sonnets were written by Willie Hughes. Librarian Lyster drops a quick “well-actually” on Best, reminding him that Wilde’s story explains how the sonnets were written for Willie Hughes rather than by him. While this is accurate, there is a brief passage in “Mr. W.H.” that matches Mr. Best’s mistake:

“As for the other suggestions of unfortunate commentators, that Mr. W. H. is a misprint for Mr. W. S., meaning Mr. William Shakespeare; that “Mr. W. H. all” should be read “Mr. W. Hall”; that Mr. W. H. is Mr. William Hathaway; and that a full stop should be placed after “wisheth,” making Mr. W. H. the writer and not the subject of the dedication…”

In my head canon, it’s been a minute since Mr. Best read the story, and though he is incorrect in the grand scheme of things, he is correctly remembering a Shakespearean abstrusiosity from Wilde’s story, proving that Mr. Best is not a total buffoon. #JusticeforMrBest

I don’t think Joyce included this allusion just for the sake of introducing some arcane Shakespeare trivia, though. It hints at the weakness of Stephen’s theory, as it tells the story of a paper-thin Shakespeare theory based in conjecture that falls apart about as catastrophically as a literary theory can (seriously, “Mr. W.H.” has a body count). Of more interest to me, though, is that it introduces the theme of homosexual subtext in Shakespeare, and by extension, in Ulysses.

After Mr. Best praises Wilde’s story a bit more, Stephen thinks the following retort to himself:

“His glance touched their faces lightly as he smiled, a blond ephebe. Tame essence of Wilde.”

I’ve written elsewhere about Joyce’s use of the term “ephebe” in the context of Best’s biography and why I find it homophobic, so I will now explore it in terms of Oscar Wilde’s biography. The term “ephebe” originates in ancient Greece and means the younger man in a specific type of male-male relationship. An ephebe in this system would be in his mid- to late- teens, and his older partner would be in his mid-twenties. Such a relationship came with a specific set of ideals and rules governing intimacy and sex. It’s worth pointing out that the ancient Greek version of such a relationship was nothing like the Victorian version, or the Elizabethan version, or the 21st century version. If you’d like more details on this historical context, I recommend reading the article “Youth by the Sea: The Ephebe in ‘A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man’ and ‘Ulysses’” by Joseph Kestner, who goes into far more detail than I have space for here. The important takeaways here are the age gap and the male-male relationship.

While this remark comes across as a bit snarky in the context of Ulysses, the concept of ancient Greek same-sex relationships was quite important to Wilde, so much so that he made it part of his defense at trial in 1895. He saw his relationship with Lord Alfred Douglas as part of the lineage of such relationships. Wilde placed his own partnership within the context of this tradition, as well as Shakespeare’s connection with the Fair Youth. From Wilde’s trial testimony:

Oscar Wilde & Lord Alfred Douglas

“‘The Love that dare not speak its name’ in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep, spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect…. It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection. There is nothing unnatural about it. It is intellectual, and it repeatedly exists between an elder and a younger man, when the elder man has intellect, and the younger man has all the joy, hope and glamour of life before him. That it should be so the world does not understand. The world mocks at it and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it.”

Much is made of Best’s youthful beauty in “Scylla and Charybdis,” and pairing him with an allusion to Wilde’s aestheticism strengthens this characterization. The term “ephebe” is quite a specific epithet directed at Best in this passage, as Best’s portrayal here and elsewhere in Ulysses is disparagingly gay-coded. In real life, Richard Best was the younger partner in a straight relationship with a large age gap, and his sexuality was questioned by Joyce (among others) as a result.

In Ulysses, as in the works of Wilde and Shakespeare, same-sex love is never directly referred to, but at least if you’re me, you might get the vibe that the boys want to kiss each other. In “The Portrait of Mr. W.H.”, same-sex love is referred to obliquely as “friendship” or “passion,” and there is no mention of anything physical. “Beauty” is also used in a similar context (note again, Best’s strong association with beauty, who later refers to same-sex male love as “the sense of beauty”). Willie Hughes is variously referred to as “the visible incarnation of his idea of beauty”, “the master-mistress of Shakespeare’s passion”, and “the delicate minion of pleasure.” The second and third examples directly borrow language from Sonnet 20.

Such ambiguity can sometimes be interpreted by current-day readers that these boys were just really, really good friends. As such, I think it’s worth considering the stakes of being openly gay in the UK at the turn of the twentieth century. Oscar Wilde had been dragged through a humiliating series of high-profile trials, destroying him personally, professionally and financially, and precipitating his death less than ten years before the events of Ulysses, all for the crime of loving another man. Such a humiliating scandal had a chilling effect in an already closed, repressive society. Writing openly of such relationships could be perilously dangerous. If such writing or speech made it through a censor at all, the mere knowledge of such matters was a confession. As scholar Colleen Lamos put it, “to know about homosexuality is to be its accomplice.” Same-sex relationships were still portrayed in the arts, but they had to be incredibly subtle. A prime example would be how Wilde had to tone down bits of The Picture of Dorian Gray in order to get it published. The boys may seem like only the best of platonic friends, but I assure you, those boys want to kiss each other.

I don’t think that we should assume upstanding citizens like Stephen Dedalus and Buck Mulligan are totally naïve when it comes to same-sex love, either. Lamos stated that “reading homosexuality is an explicit and recurrent concern in Scylla and Charybdis,” popping up in discussions of the sonnets as we’ve seen, in the banter of Buck Mulligan, and in references to Wilde. Scholar Frances Devlin-Glass argues that Mulligan was inspired as much by Oscar Wilde as he was by Oliver St. John Gogarty. Joyce wrote in a letter to his brother Stanislaus that he saw Gogarty as an imitator of Wilde.

Devlin-Glass pointed to Mulligan’s “corpulence” and his bright, colorful “dandified” wardrobe, particularly his choice of yellow, an allusion to Wilde’s “cult of the sunflower.” It’s pure speculation on my part, but it is also possible Mulligan’s choice of a primrose-colored waistcoat in “Telemachus” may be an allusion to Archibald Primrose, the 5th Earl of Rosebery, who allegedly had a relationship with Francis Douglas, brother of Wilde’s Lord Alfred Douglas. The Douglases’ father, the Marquess of Queensberry, complained about Primrose and his first-born son in a letter produced as evidence during Wilde’s trial. Apart from his wardrobe, Mulligan’s appearance in “Scylla and Charybdis” is high camp, and a prime display of his subversive wit, his self-deprecating humor, and his rejection of leftover Victorian prudery, all modeled on the spirit of Wilde. Stephen thinks of Mulligan as possessing the “Manner of Oxenford,” implying that Mulligan knows about same-sex love due to his Oxford education, another quality he shares with Wilde. Joyce wrote elsewhere that private all-male British schools were a hotbed for the love that dare not speak its name, an idea we’ll return to momentarily.

If Lamos is right, that to admit knowledge of homosexuality is to be its accomplice, then Mulligan is homosexuality’s righthand man, as he is totally uninhibited about broaching the topic in conversation. Because it’s Mulligan we’re discussing, we of course have to add a massive truckload of salt to his commentary. Lyster says of “Mr. W.H.”, “The mocker is never taken seriously when he is most serious,” and this paradox is easily applied to the Wildean presence of Buck Mulligan. We can never really know how seriously we’re meant to take him as our resident court jester, but all the same he’s not exactly wrong all the time either. Such is the riddle of Buck Mulligan.

Mulligan operates as a stark foil to the more straight-laced Lyster and Eglinton, adding depth to their characters. Both adopt a more conservative and heterosexual interpretation of Shakespeare’s sonnet love triangle. For instance, Lyster says:

“Nor should we forget Mr Frank Harris. His articles on Shakespeare in the Saturday Review were surely brilliant. Oddly enough he too draws for us an unhappy relation with the dark lady of the sonnets. The favoured rival is William Herbert, earl of Pembroke.”

In this interpretation, Lyster defers to Shakespeare scholar Harris who had a fairly traditional view of men and women, and Mr. W.H. is Shakespeare’s rival rather than the object of his affections. All well and good, nothing particularly scandalous, but nothing particularly interesting either. Mulligan has a much spicier take:

“Say that he is the spurned lover in the sonnets. Once spurned twice spurned. But the court wanton spurned him for a lord, his dearmylove.”

Mulligan’s comment is more in line with Wilde’s story: the Dark Lady stole Shakespeare’s boyfriend and not the other way around. Stephen dashes off a silent “Love that day not speak its name” in response. This notion rankles John Eglinton, who hastily attempts to correct Mulligan:

“As an Englishman, you mean, John sturdy Eglinton put in, he loved a lord.”

Oh Eg, bless your heart. Eglinton has appointed himself the group’s moral arbiter, an allusion to his Presbyterian roots. Stephen refers to him later in the episode as a “dour recluse,” in part because of Eglinton’s celibacy. Eglinton’s abstemious personality is offended by Mulligan’s open declaration of Shakespeare’s dearmylove. In the end, Eglinton’s austere lifestyle becomes an object of mockery for the younger men, as the closing lines of Mulligan’s verse that appear towards the end of the episode are clearly directed at ol’ Eg:

Buck Mulligan reciting rude poetry

“And that filibustering filibeg

That never dared to slake his drouth,

Magee that had the chinless mouth.

Being afraid to marry on earth

They masturbated for all they were worth.”

As Eglinton comes across as a bit stodgy overall, it is also implied that his ideas have become calcified. He is overly concerned with propriety and steadfast morals, which makes him shallow and naïve in turn. I guess what I’m saying is that while there are multiple interpretations of Sonnet 20, it's not a particularly patriotic text, a fact lost on Eglinton because of his ignorance about the diverse possibilities of human sexuality. The boys want to kiss, Eg.

Mulligan’s interjection about his conversation with Shakespeare scholar Edward Dowden is a bit more problematic:

“O, I must tell you what Dowden said!

—What? asked Besteglinton....

—Lovely! Buck Mulligan suspired amorously. I asked him what he thought of the charge of pederasty brought against the bard. He lifted his hands and said: All we can say is that life ran very high in those days. Lovely!

Catamite.

—The sense of beauty leads us astray, said beautifulinsadness Best to ugling Eglinton.”

Mulligan’s question about Shakespearean pederasty requires us to consider how youthful the Fair Youth might have been. The main candidates for the Fair Youth’s identity would have been adults when Shakespeare was writing his sonnets, and we can’t know Willie Hughes’ age since he didn’t exist (sorry, Willie Hughes truthers). It’s also possible that “pederasty” is used to refer to a relationship with a large age gap, but not necessarily involving a literal child. Two men in a relationship with a legal age gap (like Wilde and Douglas) would have been scandalous enough in this context. However, there is a longstanding stereotype that gay men are sexual predators of children, which I believe is present in Mulligan’s comments here and elsewhere in “Scylla and Charybdis.” Dowden’s answer is noncommittal, which I suppose is fine since we know almost nothing about Shakespeare’s biography. He is likely aware that he shouldn’t take Mulligan’s rude question too seriously. Best refers to a “sense of beauty” here, meaning male-male love. Describing him as “beautifulinsadness Best” implies that he has a strong “sense of beauty,” whereas “ugling Eglinton” implies he is far from any sense of beauty of any kind.

Leopold Bloom meets Venus Callipyge

Mulligan’s homophobic stereotyping rears its head again when he spots Leopold Bloom in the Reading Room asking after a copy of the Kilkenny People. Mulligan casts aspersions at Bloom, first telling Stephen that Bloom is “Greeker than the Greeks” as he had spied Bloom in the National Museum gazing upon the “mesial” groove” of “Venus Callipyge.” Never mind that it was female butts that attracted Bloom, any anal focus at all could be interpreted as gay. The term “sodomy” would have had a much more expansive definition in earlier eras than it does now. “Sodomy” potentially referred to anything from handjobs to bestiality and anything in betweem, as it was applied to most any non-procreative sex act, depending on the time and place it was being used.

Towards the end of “Scylla and Charybdis,” Mulligan once again spots Bloom, and says to Stephen:

“The wandering jew, Buck Mulligan whispered with clown’s awe. Did you see his eye? He looked upon you to lust after you. I fear thee, ancient mariner. O, Kinch, thou art in peril. Get thee a breechpad.”

Including “wandering jew” in his banter adds a touch of antisemitism to the mix. Mulligan is winding up Stephen here, of course, but still he insinuates Bloom is a predator or rapist because of his “greekness.” Bloom’s alleged deviance from the sexual norm is conflated here with a distorted, predatory version of homosexuality, with Stephen as its target.

Stephen, unlike Mulligan, doesn’t discuss homosexuality openly, but we should not assume he is naïve, either. He doesn’t take the bait in Mulligan’s bawdy comments, as he knows that arguing with Mulligan will only amuse the mocker further. He’s not confused or scandalized by Mulligan’s comments like Eglinton, though. They are generally followed with a silent remark indicating that Stephen knows he’s talking about gay sex. Any allusions outside of these brief remarks are incredibly subtle. After recounting an imagined version of Shakespeare and Richard Burbage’s sexcapades, Stephen thinks to himself:

“Cours la Reine. Encore vingt sous. Nous ferons de petites cochonneries. Minette? Tu veux?”

And after Eglinton argues that Shakespeare loved the Fair Youth as an Englishman loves a lord, Stephen entertains the following thought:

“Old wall where sudden lizards flash. At Charenton I watched them.”

Lamos wrote that Charenton refers to a town southeast of Paris where the Marquis de Sade, famed sexual deviant, was imprisoned. Gifford and Seidman’s Ulysses Annotated translates the French as “Another twenty sous [one franc]. We will indulge in little nasty things. Pussy, [darling]? Do you wish [it]?” Lamos believes “little nasty things” very vaguely implies oral sex as offered by a sex worker. According to Lamos, these two silent interludes imply that while in France, Stephen watched a non-standard (to him) sex act (probably oral sex) and enjoyed it. Though this erotic adventure involved watching other men engaged in heterosexual sex, it was gay enough for the early 1900’s. And because Stephen enjoyed it, this has unsettled his sexual identity.

Beyond this, Stephen reflexively responds to homosexual innuendo with a reference to Wilde throughout the novel as a whole, typically with the phrase “the love that dare not speak its name.” This phrase is taken from the poem “Two Loves” by Lord Alfred Douglas and was used against Wilde at trial. In turn, Wilde used this term to defend himself, as quoted above. The subtext of homosexuality in this phrase is clear within the context of Ulysses, as well as the various allusions to Wilde scattered throughout the novel. In “Telemachus,” Mulligan says, “We have grown out of Wilde and paradoxes.” To outgrow something inherently implies that one was once involved in it. Is Mulligan merely referring to an intellectual interest in Wilde, or is he referring to something more personal? We don’t get any hard and fast answers in Ulysses, so we have no choice but to let our imaginations run wild.

Buck Mulligan as a Shakespearean fool

And what about the great arranger himself, James Joyce? Do we have any indication of what he actually intended with regard to this homosexual subtext? As mentioned previously, the chilling effect that Wilde’s trial had on frank literary discussion of queer love or sexuality cannot be overstated. Joyce would have been keenly aware of this, but like Wilde and Shakespeare, found ways to talk about same-sex love obliquely. A fictionalized dialectic around Stephen Dedalus’ Shakespeare theory allows for just such a scenario. Joyce can put the words into the mouth of an absurd clown like Mulligan, but like Shakespeare’s fools, that is where truth can be found.

Devlin-Glass writes that Joyce worked in a paradigm of compulsory heterosexuality and avoided explicitly writing about homosexual relationships. Wilde and Shakespeare’s work and lives also reflect compulsory heterosexuality - both married women. In Shakespeare’s case, though he wrote some sexy sonnets to the Fair Youth, he also wrote a bunch urging the Fair Youth to get married. All three men lived in societies where it was structurally impossible to be openly gay, but that doesn’t mean that people didn’t have those feelings and didn’t fall in love with people of the same sex. And what about Joyce? Stanislaus Joyce wrote of his brother’s sexuality in My Brother’s Keeper:

“He considered sexual contact a necessary physical fulfillment and made no apologies for it. He recognized that nature does not allow adolescent or adult males to be continent, that in a less unpleasant way chastity is as much against nature as homosexuality.”

Likewise, scholar Sheldon Brivic described Joyce as a “doctrinaire heterosexual” in a 1980 book. I have previously quoted Senator David Norris’ essay “The ‘Unhappy Mania’ and Mr. Bloom's Cigar: Homosexuality in the Works of James Joyce” in which he states, “my personal belief is that homosexuality was a subject that scarcely engaged Joyce’s attention at all and of which he had little real knowledge.” After revisiting this topic, I now strongly disagree with Senator Norris.

I think Joyce’s experience of sexuality was more complex than these three interpretations allow. He certainly held some non-standard sexual interests, which are famously expressed in his letters to Nora and in Ulysses as well. Joyce’s frank depictions of non-procreative sexuality, specifically those in “Nausicaa,” are what resulted in Ulysses being banned. And as we’ve noted above, interest in non-procreative varieties of straight sex could be conflated with homosexuality or sodomy in the early twentieth century. Stanislaus’ statement feels closer to his own beliefs rather than to those of his brother. Lamos writes Joyce acknowledged elsewhere that “homosexual desires are common” and while not enthusiastically endorsing them outwardly, also refused to condemn them outright.

Joyce wrote about Oscar Wilde’s legacy in the 1909 essay “Oscar Wilde: The Poet of Salome.” Joyce held views about Wilde’s “unhappy mania,” as he called it, that wouldn’t hold up today, specifically that Wilde’s sexuality was a result of a dysfunctional relationship with his mother and his education in the homosocial environment of all-boys English education. He medicalizes Wilde’s sexuality, as was common in that era. Though Joyce never directly calls Wilde “homosexual,” he also doesn’t refer to him by the then common medical term “invert.” Joyce is nonjudgmental towards Wilde, viewing him as a scapegoat but also seeing him as sexless. Devlin-Glass notes an overall decline in “homosexual panic” in the works of Joyce between this essay in 1909 and the publishing of Ulysses in 1922. I don’t think Joyce had an intimate knowledge of what it was to be a gay man in these decades, but I don’t think he was utterly ignorant and I don’t think he was utterly uninterested. He knew gay people in his social and professional life in continental Europe. Ulysses may never have been published at all without the support of queer women like Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monier. My god, we don’t even have time to get into the erasure of queer women in this era.

In the end, any homosexual innuendo in Ulysses is buried between the lines, but I feel that it would be dishonest to deny its presence. If Ulysses is a book about everything, then it must necessarily include queer love. Given this ambiguity we must use our discernment to draw our own informed conclusions. In that spirit, I’ll leave you with my hottest take of all: it’s now official Blooms & Barnacles canon that Buck Mulligan, William Shakespeare, and probably Stephen Dedalus are disaster bisexuals. If you’re not familiar with the term, scholar Hannah McCann defines it as:

“a bisexual character or person who has chaotic energy or causes chaos. It seems to be a term used with some affection (“oh what a disaster bisexual!”) and often personal identification (“I’m such a disaster bisexual!” – to which everyone replies “yes”). The disaster bisexual is not your typical queer-coded villain, but rather, an anti-hero. The term seems to pleasurably press the bruise of internalised biphobia. When you cannot corral your desires into a neat monosexual storyline, this can feel chaotic.”

I can’t think of a better description of Buck Mulligan’s whole… thing. I’m also glad to know that we bisexuals were out there being chaotic long before we had worked out the language to talk about it.

Further Reading:

Brivic, S. (1980). Joyce between Freud and Jung. Port Washington: Kennikat Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/joycebetweenfreu0000briv/mode/2up

Chua, X. (2016). A Queer Reading of James Joyce’s Ulysses. https://www.academia.edu/40125344/A_Queer_Reading_of_James_Joyces_Ulysses

Devlin-Glass, F. (2005). Writing in the Slipstream of the Wildean Trauma: Joyce, Buck Mulligan and Homophobia Reconsidered. The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, 31(2), 27–33. https://doi.org/10.2307/25515592

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/vy6j4tk

Haas, K. (2015, Mar 27). Thomas Tyrwhitt, Oscar Wilde, Mr. W.H., and James Joyce. The Rosenbach. https://rosenbach.org/blog/thomas-tyrwhitt-oscar-wilde-mr-wh-and/

Joyce, J. (1989). Oscar Wilde: The poet of Salome. In E. Mason & R. Ellmann (eds.), The critical writings of James Joyce. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/criticalwritings00joyc/mode/2up

Kestner, J. A. (1994). Youth by the Sea: The Ephebe in “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man” and “Ulysses.” James Joyce Quarterly, 31(3), 233–276. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25473567

Lamos, C. (1998). Deviant modernism : sexual and textual errancy in T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, and Marcel Proust. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/deviantmodernism0000lamo/page/150/mode/2up

McCann, H. (2024, March 27). The rise and rise of the disaster bisexual. BINARYTHIS. https://binarythis.com/2024/03/27/the-rise-and-rise-of-the-disaster-bisexual/

Slote, S., (2024) “As Camp as a Row of Pink Tents: Stephen’s Portrait of Mr W. S.”, Open Library of Humanities 10(1). doi: https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.15270

Was Shakespeare Gay? (n.d.). Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. https://www.shakespeare.org.uk/explore-shakespeare/podcasts/lets-talk-shakespeare/was-shakespeare-gay/