The Love That Dare Not Speak Its Name

To listen to a discussion of this topic, check out the podcast episode here.

On page 49 of “Proteus,” Stephen Dedalus spends a paragraph thinking about his shoes, which feels appropriate rounding out an episode that consists of walking on the shore:

His gaze brooded on his broadtoed boots, a buck's castoffs, nebeneinander. He counted the creases of rucked leather wherein another's foot had nested warm. The foot that beat the ground in tripudium, foot I dislove. But you were delighted when Esther Osvalt's shoe went on you: girl I knew in Paris. Tiens, quel petit pied! Staunch friend, a brother soul: Wilde's love that dare not speak its name. His arm: Cranly's arm. He now will leave me. And the blame? As I am. As I am. All or not at all.

Tramping around Sandymount in boots borrowed from Buck Mulligan, Stephen is aware of his reliance on the snarky medical student for his material necessities, including his bed in the Martello Tower. We also learn a new tidbit about Stephen’s time in Paris - he once tried on a female friend’s shoe and “delighted” when it fit. These details accompany a few memorable names -Wilde, as in Oscar, and Cranly, as in Stephen’s erstwhile confidant from A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. One phrase in particular stands out: “Wilde’s love that dare not speak its name.” Might Mulligan or Cranly have been more than a “staunch friend” or “brother soul” to Stephen?

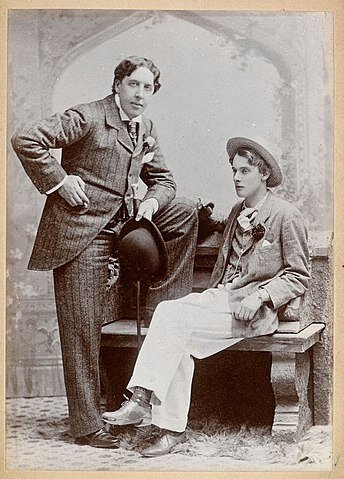

Wilde and Douglas in 1893

The phrase “the love that dare not speak its name,” though often attributed to Wilde, was actually written by Lord Alfred Douglas in an 1892 poem called “Two Loves.” He and Wilde were involved in an affair, which Douglas’ father, the Marquess of Queensbury, strongly disapproved of. Wilde sued the Marquess for libel, but the ensuing trials resulted in Wilde’s imprisonment. “Two Loves” and the “love that dare not speak its name” were used as evidence to condemn Wilde of homosexuality. By 1904, Wilde has been dead for four years, but his legacy is still in the air in Dublin.

Fun fact: there is one (likely coincidental) connection between Ulysses and the life of Oscar Wilde: Wilde was 38 years old when he first met 22-year-old Douglas. Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus are the same ages respectively when they meet on Bloomsday in 1904.

“The love that dare not speak its name” is sandwiched between the phrases “Staunch friend, a brother soul” and “His arm: Cranly's arm.” Since the first three sentences indicate Stephen is thinking of Mulligan, it would seem he is the “staunch friend” and “brother soul” Stephen is thinking of, though it could also be easily interpreted as Cranly. I think it’s likely a bit of Column A and Column B, as Mulligan fades into Cranly in Stephen’s memories. So, what’s going on here? How close was Stephen to Mulligan and Cranly? Were they more than just friends?

In “Telemachus,” Oscar Wilde is mentioned by name twice, both times by Buck Mulligan. This first instance on page 6 occurs as Stephen, looking generally unkempt and unwashed, peers into a broken mirror as Mulligan quips:

The rage of Caliban at not seeing his face in a mirror…. If Wilde were only alive to see you.

We learn later that Stephen looks and smells pretty scruffy as he refuses to bathe, so this comment seems to be a dig at Stephen’s appearance, perhaps bearing a resemblance to the brutish monster Caliban of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. This line, however, is inspired by the preface to Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray:

The nineteenth century dislike of Realism is the rage of Caliban seeing his own face in a glass.The nineteenth century dislike of Romanticism is the rage of Caliban not seeing his own face in a glass.

Stephen’s deft reply, “It is a symbol of Irish art. The cracked lookingglass of a servant,” is a commentary on the subservience of Irish art and artists, always second class to their British masters. Likening Irish artists to Caliban adds to the disdain heaped on aspiring poets like Stephen. Mulligan, the upperclass Irishman, only sees value in Stephen’s words when they can be sold cheaply to Haines of Oxford. “If Wilde were only alive to see you” is also a comment on Stephen’s lowly status.

Later in the same episode, on page 18, as Stephen and the boys are leaving the tower for a morning dip, Haines asks Stephen if his Shakespeare theory is “some kind of paradox.” Mulligan naturally interrupts, saying:

Pooh!... We have grown out of Wilde and paradoxes.

Some of Oscar Wilde’s most famously witty quotes are paradoxical, things like “There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.” This comment shows that Mulligan believes that Stephen has gotten a little too big for his breeches with his convoluted Shakespeare theory, which he “proves through algebra.” He’s too fancy now for the simplicity of a mere paradox.

So, why tie Mulligan to Wilde? I don’t think that Mulligan or Stephen is necessarily secretly gay, but I do think that their friendship was once closer and more intimate than we see in “Telemachus.” One reason Mulligan’s betrayals sting so much for Stephen is that they are coming from someone who was once an intimate friend. Stephen desperately wants Mulligan’s approval, but rather than receiving it, he’s been replaced by Haines, who possesses the material wealth to be on par with Mulligan, classwise. Another reason is that while Mulligan is a traditionally masculine character (athletic, heroic, dominant), Stephen embodies none of these characteristics. He is instead weak, frightened and dominated. Mulligan is likely just as irritated with Stephen as Stephen is with him, and he has a pattern of using homophobic insults against men he doesn’t respect.

The phrase “Cranly’s arm” appears twice in the first three episodes of Ulysses - once here in “Proteus” and once in “Telemachus” after Mulligan proclaims:

God, Kinch, if you and I could only work together we might do something for the island. Hellenise it.

There is an implication of homosexuality in Mulligan’s desire for hellenisation, as later in “Scylla and Charybdis,” he refers to Bloom as “Greeker than the Greeks,” mocking him for perceived homosexuality.

Though he doesn’t appear as a character in Ulysses, Cranly was a major figure in Stephen’s life in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Though they were close friends, Stephen’s relationship with Cranly was fraught in a way distinct from his relationship with Mulligan. Rather than being too frivolous and rude like Mulligan, Cranly is characterized as being too austere and serious in temperament. They share a tense and passionate disagreement in the closing pages of Portrait over Stephen’s defection from religion and, ultimately, Ireland.

Like Buck Mulligan, Cranly is based on a real friend from Joyce’s life, John Francis Byrne. Byrne and Joyce shared a close, intimate relationship, though, like Stephen and Cranly, Byrne was more serious and earnest in character than Joyce and more devout in his Catholicism. As told by Joyce’s younger brother Stanislaus, Joyce and Byrne had a falling out around the time Joyce moved to Paris.

Byrne had received a postcard inscribed with a poem from Joyce and boasted to their mutual friend Vincent Cosgrave (Lynch in Ulysses) that he knew Joyce better than anyone in Dublin, proven by this incredibly personal missive from Paris. Cosgrave produced an identical postcard, but rather than containing a bit of verse, it detailed Joyce’s exploits in various Parisian brothels. Byrne was totally unaware of this side of Joyce. His offense and Joyce’s lack of repentance left their friendship irreparably fractured. It was around that time that Joyce became friends with Oliver St John Gogarty. On a trip to Ireland in 1909, Joyce visited Byrne at his Dublin home, 7 Eccles St.

Stanislaus wrote in his biography of his brother:

Byrne’s anger was not based on moral disapproval. He took it as a personal offence to him that there should be something concerning my brother that others knew and he did not know. My brother, too, had humoured his friend’s possessiveness so far that Byrne began to think he had established rights of control over my brother’s life…. Manifestly, some kind of idol had fallen and was shattered.

This sentiment is reflected in Stephen Hero, Joyce’s unpublished manuscript that later became Portrait. Stanislaus’ counterpart Maurice warns Stephen that Cranly is trying to gain power over him. In Portrait, Stephen and Cranly’s falling out is more subtle, ultimately parting ways after debating Stephen’s decision to leave Ireland and take up a life of self-imposed artist exile.

In this scene, Stephen pledges:

I will not serve that in which I no longer believe, whether it call itself my home, my fatherland or my church: I will try to express myself in some mode of life or art as freely as I can and as wholly as I can, using for my defence the only arms I allow myself to use, silence, exile and cunning.

And then:

Cranly seized his arm and steered him round…. He laughed almost slyly and pressed Stephen’s arm with an elder’s affection.

In “Telemachus” and “Proteus,” Stephen flashes back to this affectionate touch, “His arm: Cranly's arm. He now will leave me. And the blame? As I am. As I am. All or not at all.” Stephen clearly associates Cranly’s warm embrace of his arm at their parting with Mulligan’s special mix of mockery and caretaking. He is also coming to a realization that his friendship with Mulligan is ending. He wants a friend to accept him as he is, “all or not at all,” a test both Mulligan and Cranly failed. Outgrowing Wilde means that these intimate male relationships are for youth only; artistic exile means abandoning them entirely. Stephen debates this point in Portrait with Cranly, saying he will risk being totally alone for the sake of his art. Their conversation ends thus:

--And not to have any one person -- Cranly said -- who would be more than a friend, more even than the noblest and truest friend a man ever had.

His words seemed to have struck some deep chord in his own nature. Had he spoken of himself, of himself as he was or wished to be? Stephen watched his face for some moments in silence. A cold sadness was there. He had spoken of himself, of his loneliness which he feared.

-- Of whom are you speaking? Stephen asked at length.

--Cranly did not answer.

Stephen’s declaration of exile deeply affects Cranly, who is not ready to be set aside. As far as I can see, Stephen interprets this as fear of being alone. However, this scene is sometimes referenced as gay panic on Stephen’s part, causing Stephen to abandon Cranly as a friend. In this interpretation, his recurring thoughts of Cranly’s arm are a mental shudder at the “love that dare not speak its name.” For my part, I feel like there is something more than platonic in Cranly’s words. I don’t see the panic on Stephen’s end, though. If anything, his friend has just declared his love for him, and Stephen is too naïve to understand the depth of Cranly’s sadness at their parting. The following passages of Portrait are written as diary entries. Stephen comments on this conversation, characterizing Cranly as “having a grand manner on” and “attacking [him] on the score of love for one’s mother.” While it’s possible he omitted details from his own diary, I think that Stephen’s ire for Cranly is mostly philosophical.

James Joyce (right) with John Francis Byrne (center) and George Clancy (c. 1900)

Portrait is, at its core, a book about a boy growing into a young man. It’s telling that Mulligan informs Haines that, “We have grown out of Wilde…” Stephen’s youth was crowded with intimate relationships with other men but very few with women. Stephen’s only relationships with women are either distant (his mother) or purely sexual (prostitutes), a product of Victorian gender segregation. His schooling took place entirely in all-boys schools. The one exception, you’re probably screaming in your head, is Emma Clery, the closest thing that Stephen has to a love interest in Portrait. However, Stephen’s friendship with Cranly, not Emma, dominates the latter portion of the novel. In Ulysses, Stephen’s main interactions with women are his mother’s spectre and those he meets in Bella Cohen’s brothel.

I don’t think that Stephen spends all his time with other men out of romantic or sexual interest, but instead because that is the only option afforded him by the rigid, conservative culture of his era. If Stephen had lived in 2020, perhaps he could have rich friendships with women rather than the macho dudes in 1904 Dublin who mock and denigrate him. He clearly desires touch, as expressed two paragraphs back, “I am quiet here alone. Sad too. Touch, touch me.” While it’s possible that Stephen is repressing gay feelings for the entirety of two novels, I think it’s more likely that Stephen is simply unable to make the type of connections that, deep down, he needs. This gentle friend role will ultimately be filled by Leopold Bloom.

While queer theorist readings of Ulysses do exist, I’d like to turn to the writing of Senator David Norris for insight on homosexuality in the works of Joyce. If you’re not familiar with Senator Norris, he is an Irish senator, a Joyce scholar, and the first openly gay man elected to public office in Ireland. He helped to overturn Ireland’s anti-gay laws, the very same used to convict Oscar Wilde. In 1994, James Joyce Quarterly printed an issue focusing entirely on queer issues and James Joyce. Norris’ contribution was the best source I read while researching this post. As I don’t think there is anyone so uniquely qualified to write on this particular topic, I recommend checking out his article.

Senator Norris wrote that Joyce, who referred to Wilde’s homosexuality as an “unhappy mania,” mistakenly believed that the public school system in which he was educated created homosexuality in young men. This would account for the intense feelings between young men in close quarters like Stephen and Cranly, or Stephen and Mulligan, but these feelings would be outgrown in manhood. Of Cranly and Stephen’s conversation at the end of Portrait, Norris wrote that “the function of this suggestion… is to place Cranly in the position of adoring acolyte than to flesh out any sexual suggestion.” This reading would be more in line with what Joyce’s brother Stanislaus had written about Joyce and Byrne’s friendship. Senator Norris closes by saying, “my personal belief is that homosexuality was a subject that scarcely engaged Joyce’s attention at all and of which he had little real knowledge.”

This is obviously a very complex and sensitive topic. Readers want to see themselves reflected in their favorite media, whether it is Stephen Universe or Stephen Dedalus. There’s nothing wrong with reading deeper feelings into the characters in Ulysses, though I tend to agree personally with Senator Norris when he wrote, “attempts to impose a sexualization of Joyce’s narrative in a book like Ulysses are likely to come unstuck.” Joyce wrote about many taboo subjects in Ulysses. If he had wanted to portray homosexuality, I think he would have done so more overtly. On the other hand, if you have a Stephen Dedalus/Buck Mulligan slashfic you are dying to share, I am very easy to find on social media.

Further Reading:

Carosone, M. (2017, Jun 19). Bending instead of queering Ulysses: A gay male reading of James Joyce’s novel. HuffPost. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/vobhxq9

Ellmann, R. (1959). James Joyce. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Joyce, S. (1958). My brother’s keeper: James Joyce’s early years. New York: The Viking Press.

Kimball, J. (1987). Love and Death in "Ulysses": "Work Known to All Men". James Joyce Quarterly,24(2), 143-160. Retrieved fromhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/25476793

Lamos, C. (1994). Signatures of the Invisible: Homosexual Secrecy and Knowledge in "Ulysses". James Joyce Quarterly, 31(3), 337-355. Retrieved fromwww.jstor.org/stable/25473571

Norris, D. (1994). The "Unhappy Mania" and Mr. Bloom's Cigar: Homosexuality in the Works of James Joyce. James Joyce Quarterly,31(3), 357-373. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/25473572