The Word Known to All Men

To listen to a discussion of this topic, check out the podcast episode here.

“Touch me. Soft eyes. Soft soft soft hand. I am lonely here. O, touch me soon, now. What is that word known to all men? I am quiet here alone. Sad too. Touch, touch me.”

The lines above appear towards the end of “Proteus,” page 49 in my copy (1990 Vintage International), as Stephen pens the first draft of his poem while reclining on a rock on Sandymount Strand. Our key line today is Stephen’s unanswered question: “What is that word known to all men?” James Joyce seemingly never met an obscure allusion or rambly list that he didn’t love. Naturally, posing a question and not giving a concrete answer is solidly in line with his style.

Before we attempt to tease an answer out of the text, let’s give Stephen’s question some context. Our Young Artist is trying to conjure just the right words for his poem and is distracted by his own thoughts. The previous paragraph reads:

She trusts me, her hand gentle, the longlashed eyes. Now where the blue hell am I bringing her beyond the veil? Into the ineluctable modality of the ineluctable visuality. She, she, she. What she? The virgin at Hodges Figgis' window on Monday looking in for one of the alphabet books you were going to write. Keen glance you gave her. Wrist through the braided jess of her sunshade. She lives in Leeson park with a grief and kickshaws, a lady of letters. Talk that to someone else, Stevie: a pickmeup. Bet she wears those curse of God stays suspenders and yellow stockings, darned with lumpy wool. Talk about apple dumplings, piuttosto. Where are your wits?

As Stephen writes his poem, he has been considering his future acclaim and eventual legacy as a poet. Will anyone ever actually read his writing or will he toil in obscurity? Stephen imagines an admirer of his, brings “beyond the veil” of his mind, this young, virginal woman peeking through the window of Hodges Figgis, looking for Stephen’s as-yet-unrealized books with letters as titles (Have you read his F? O yes, but I prefer Q. Yes, but W is wonderful. O yes, W.)

Stephen’s thought-interrupting distractions are predictable at this point: his dead mother, Haines’ naïvety, Buck Mulligan’s disrespect. Here we find a new dimension: Stephen is incredibly lonely. Though Stephen has some bigger fish to fry, he craves love and companionship like the rest of us non-geniuses. June 1904, as an aside, was when Joyce met Nora Barnacle, his future wife, but he afforded his literary avatar no such comfort. In fact, he felt that Stephen needed to be completely alone in order to convey the isolation of the young Artist, but Stephen still craves touch. Perhaps this is a clue to deciphering Stephen’s Word Known to All Men. “Proteus” isn’t the only appearance of Stephen’s Word, though. He also demands an answer from his mother’s ghost when she appears to him in Bella Cohen’s brothel at Ulysses’ climax in “Circe” (p. 581):

STEPHEN (Eagerly.) Tell me the word, mother, if you know now. The word known to all men.

Stephen’s mother answers his question with several other questions and then urges him to repent. Surely “repent” wouldn’t be the word known to all men. Stephen certainly doesn’t accept it, calling his mother’s spirit a “ghoul” and “hyena” in response. We readers are left in the lurch. It must have something to do with his mother, then? What connection is there between phantasmal mothers and literary fans clad in lumpy stockings?

Now, if you’re a devotee of Ulysses, you’re likely shouting, “But Kelly, the word known to all men appears a third time in Ulysses along with an answer: love. It’s love! The word is love! Duh!” This is where things get interesting. Yes indeed, in “Scylla and Charybdis,” Stephen thinks to himself in the midst of his debate with the boffins in the library:

Do you know what you are talking about? Love, yes. Word known to all men. Amor vero aliquid alicui bonum vult unde et ea quae concupiscimus …

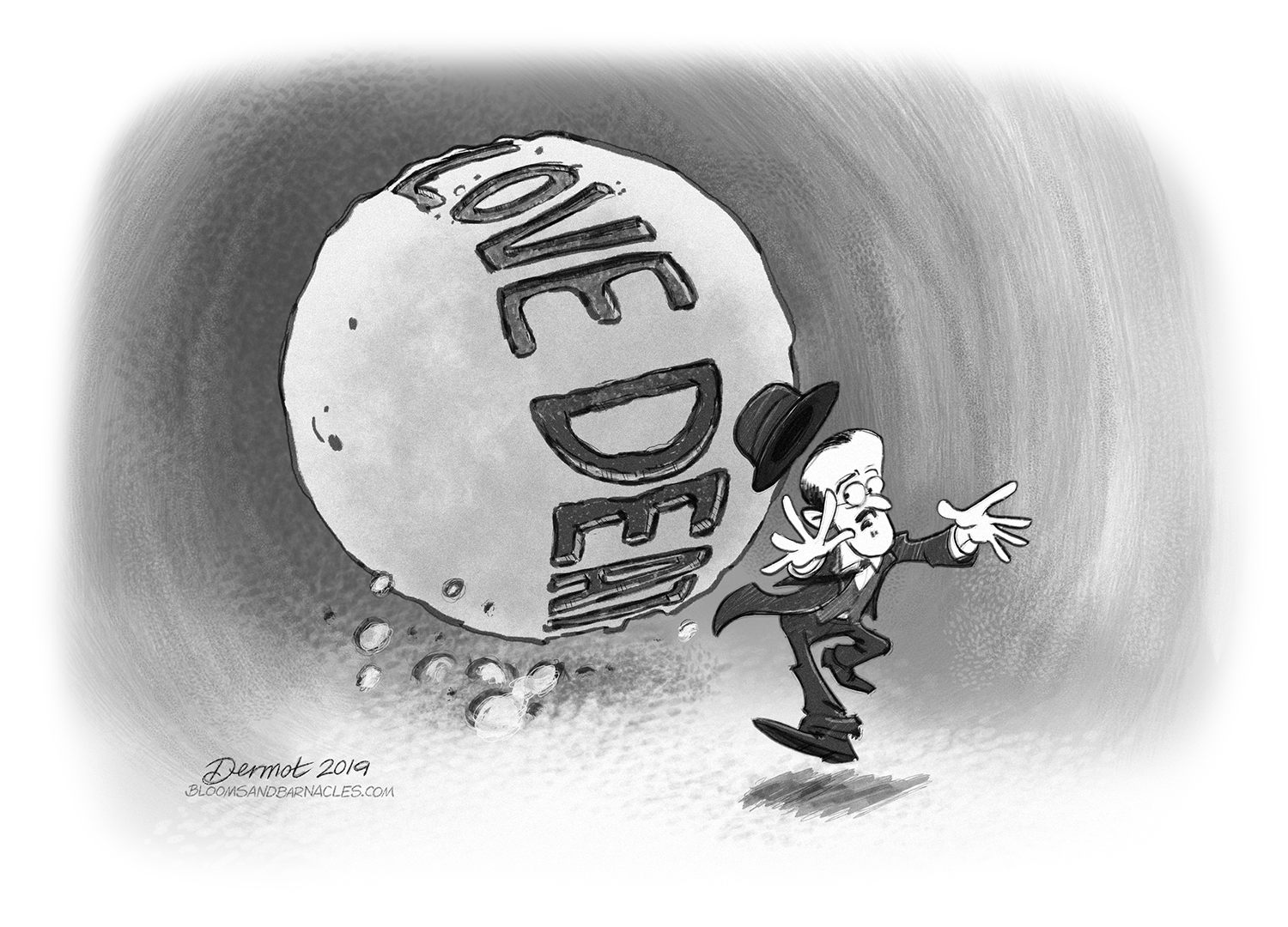

Mind-blowing literature

Or maybe he doesn’t. If you’re also reading the 1990 Vintage International edition, you’re likely getting frustrated looking for this quotation. The inclusion of these “love” lines, with their direct answer to Stephen’s question, don’t appear in every edition. A bit of Ulysses publishing history: in the original 1922 text of the novel, the love lines didn’t appear at all, leading to decades of Joyce scholars debating exactly which word was known to all men. In 1984, a new edition of Ulysses was published, edited by a scholar called Hans Walter Gabler, and included around 5,000 edits. These changes ranged from correcting punctuation and spelling to the addition of previously omitted material. The love lines in “Scylla and Charybdis” were the longest such restoration.

Gabler’s editorial choice was deeply controversial. He’d found these lines in Joyce’s original manuscript and assumed that a typist had mistakenly omitted them. The Latin phrase ends in an ellipsis, as does the line just before this (“—The art of being a grandfather, Mr Best gan murmur. l'art d'être grand…”). Gabler thought a careless or exhausted typist could easily have skipped from one ellipsis to another, accidentally removing this critical passage. The omission had gone unnoticed for decades, including by Joyce himself, until Gabler’s restoration in the mid-80’s. The addition of these lines seems to definitively answer Stephen’s question. It’s love, guys. We can all go home now.

You didn't think it would be that simple, though, did you?

Not all Joyce scholars were ready to accept Gabler’s edit. Though some prominent scholars - notably Richard Ellmann - had deduced that Stephen’s Word was love prior to Gabler’s edition, not everyone agreed. It could be that Joyce had written this passage and later purposely ommitted it, intentionally leaving Stephen’s Word ambiguous and open to the reader’s interpretation. After the initial publishing of Ulysses, Joyce delivered a list of errata to the publisher to be corrected, but did not mention the missing passage in “Scylla and Charybdis.”

Additionally, Joyce worked quite closely with both Frank Budgen and Stuart Gilbert on reading guides to Ulysses. It seems unlikely that Stephen’s unanswered question would have gone unremarked upon by either author. In fact, both give little more than passing mention to Stephen’s question. It seems very likely that Budgen or Gilbert would have at least asked Joyce about this mysterious Word, appearing at a pivotal moment in the novel, especially since no answer was given in those early editions. This would have alerted Joyce to the omission in “Scylla and Charybdis.” The silence on the Word makes me think that Joyce preferred to not have an official answer on the record, either in Ulysses or in a reading guide. Additionally, there is no hard evidence of the alleged sloppy typist. No documents have emerged from Joyce or the publisher mentioning this omission, which contributes to my feeling that Joyce intended the love lines to be left out.

Whether Gabler made the right decision or not is unclear. In any case, adding the love lines back into the text hasn’t dampened academic debate on the interpretation of Stephen’s Word. Interpretations pre-1984 included love and death as well as far-out guesses, such as the term synteresis, which Ellmann quipped, “sounds like the one word unknown to all men.” There isn’t space or time enough for me to go over all of them in detail, but regardless of which interpretation you prefer, they all provide some insight into the text of Ulysses. The ones I’ve favored on Blooms & Barnacles are the ones I find provide the best of those insights. They’re also admittedly the interpretations favored by some of the most eminent Joyce scholars. I’ve included links in the “Further Reading” section to a variety of interpretations of Stephen’s Word. If you want to weigh in on the debate or give a different interpretation, feel free to drop it in the comments below, on Twitter or on Facebook.

Love

Even prior to the updated Gabler edition, the champion for “love” as Stephen’s Word was Joyce biographer Richard Ellmann. He felt that the 1984 restoration of the passage in "Scylla and Charybdis" only bolstered his original hypothesis, though he reportedly “felt grave doubts” that Joyce would have wanted those lines restored.

Ellmann saw hints throughout Joyce’s writing, not just in Ulysses, of love as a major guiding theme in Stephen’s journey. In the closing lines of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Stephen’s mother “prays now, she says, that I may learn in my own life and away from home and friends what the heart is and what it feels. Amen. So be it.” I don’t think it would be a huge stretch to say that Stephen can be cold and distant from those around him. Clearly his mother wanted him to learn to let people in and to love, allowing him to grow into a happier person. After her death, Stephen is plagued by guilt over not fulfilling his mother’s final wish - that he should pray for her. Stephen’s guilt is vividly shown during the scene in “Nestor” when he reflects on amor matris, a mother’s love, as he watches young Cyril Sargent puzzle out some algebra problems. Stephen reflects:

But for her the race of the world would have trampled him underfoot, a squashed boneless snail. She had loved his weak watery blood drained from her own. Was that then real? The only true thing in life?

This passage is also a callback to Stephen’s erstwhile friend Cranly’s words about the same subject in Portrait:

Whatever else is unsure in this stinking dunghill of a world a mother's love is not. Your mother brings you into the world, carries you first in her body. What do we know about how she feels? But whatever she feels, it, at least, must be real.

Even without the love lines added to “Scylla and Charybdis,” it is abundantly clear that Stephen’s notion of love is intertwined with his mother. It makes sense then that Stephen would demand knowledge of love from his mother’s spectre in the Nighttown brothel.

As noted above, in “Proteus,” Stephen’s question first appears at the peak of a fantasy about an admiring young woman and Stephen’s desire for human touch.If love is truly Stephen’s Word, this passage would imply that he knows of it intellectually, but hasn’t connected with it emotionally. It’s also clear how alienated Stephen is by his detachment from the Word, from love.

I am not arguing, however, that Ulysses is a love story in the traditional sense, a story of a young man in search of love. Stephen is a young man in search of Truth with a capital T. If he is unable to experience love, either from a young woman with lumpy stockings or from his mother, he is missing out on a universal human experience, and thus incapable of engaging with Truth.

Ellmann points out that Ulysses can be a novel fundamentally about love while avoiding either sentimentality or didacticism because it endeavours to show love in all its forms, whether beautiful or horrific. Throughout the course of June the sixteenth, the characters experience romantic love, sexual love, masturbatory love, nationalistic love, egotistical love, parental love, brotherly love, social love. Love in Ulysses is not a high-flying inspirational beauty; it’s grubby and harsh and stubborn, just like in real life. It’s not a coincidence then that if Stephen’s search is truly about a deeper notion of love, he would demand it be revealed in a brothel, in his moment of abject darkness when he needs it most.

And of course, all this search for the knowledge of love connects Stephen with his nonconsubstantial father - Leopold Bloom. Ellmann points to the passage in “Cyclops” where Bloom, defender of love, is debating his views of history and hatred with the men Barney Kiernan’s pub:

—But it's no use, says he. Force, hatred, history, all that. That's not life for men and women, insult and hatred. And everybody knows that it's the very opposite of that that is really life.

—What? says Alf.

—Love, says Bloom. I mean the opposite of hatred.

Stephen’s alienation has stymied his happiness and creativity, and it’s not until he experiences the kindness of a stranger in Nighttown that he can begin his path towards becoming the Artist he wants to be. Bloom is the rare person who shows Stephen genuine kindness, compassion, and, dare I say, love during the course of Ulysses. Stephen has been abandoned by his friends and his biological father at his lowest point, but it’s due to the humanity of Bloom that he is delivered from his nightmare. Bloom provides the fatherly love that Stephen, like all men, needs.

Death

Alright, so the argument for love is pretty convincing, so convincing in fact, that I think it doesn’t need those pesky love lines added by Gabler in 1984. However, not all scholars agree that the Word is love, even with the love lines. Joyce scholar Hugh Kenner argued in favor of a different interpretation prior to 1984, that Stephen’s Word was death rather than love. Kenner wrote of Dublin as a “Kingdom of Death” in his 1956 book Dublin’s Joyce, in which he also characterizes Molly’s yes as the “yes” of authority over “this animal kingdom of the dead.” The first thing to consider is how universal Joyce actually believed love to be. If we expand our analysis to his other works, we find this quote about Gabriel Conroy, the protagonist of “The Dead”:

He had never felt like that himself towards any woman but he knew that such a feeling must be love.

Stephen seems to be similarly distant from those around him. As far as we know, he hasn’t been in love with a woman yet at age 22. Though he was once close with his family, he is now totally disengaged from all his closest kin. His friends are barely friends at all. As of the morning of June the sixteenth, Stephen doesn’t even have a home. He has decided in “Proteus” that he won’t return to the Martello tower that evening. Stephen clearly desires love, but the object of his desires in the lumpy stockings is purely hypothetical, just a vision from beyond the veil. Like Gabriel Conroy, Stephen intellectually understands love, but he doesn’t truly feel it. Love in Joyce’s writing may not be as universal as we assumed in our first theory since we now have found two men who seem to be disconnected from love. Two characters, it should be said, who were heavily inspired by Joyce’s own autobiography.

The spectre of Stephen’s late mother.

While the universality of love may be in question, the universality of death certainly is not. Death catches up with us all eventually, no matter how hard we deny it. Stephen is certainly acquainted with death on June sixteenth - he’s dressed in black, mourning his mother. Death dogs his every step from Sandycove to Sandymount during Bloomsday morning. His first thoughts of his mother in the morning are recalling his nightmare in which she appears as an angry ghost and then of her dying days. Most of these thoughts are tinged with guilt over his refusal to pray at her bedside, punctuated by the refrain of “agenbite of inwit,” the remorse of conscience.

Stephen's mother’s death lurks behind every aspect of his lesson at Mr. Deasy’s school, even something so simple as a nonsense riddle. On Sandymount Strand, Stephen is still incredibly preoccupied with death, ruminating on being called back from Paris due to his mother’s illness, marauding Vikings and medieval famine, the drowned dog’s body and the drowning man that Mulligan had talked about that morning. As Stephen obsesses over the deaths of others, he is actually obsessing over his own mortality. If his mother could be struck down by cancer, couldn’t he as well? Without her amor matris, who will protect this weedy boy semi-grown? Stephen’s desire to secure his legacy as a writer is a part of his death panic - he could die at any moment, so his work must be preserved for all time as soon as possible. Stephen’s initial question about his Word is couched in a desperate plea for love, but there is far more death imagery preceding it.

And of whom does Stephen demand an answer to his question? Not truly his mother as he knew her, but his mother’s angry ghost, who is at that moment demanding his repentance in a brothel. She is less clearly a symbol of the motherly love that kept alive weedy boys like Cyril Sargent and Stephen Dedalus and much more a reminder of what becomes of all those little children at the end of their lives. Stephen calls her Rawhead and Bloody Bones, a monster in traditional folklore that devours the bones of disobedient children. Rather than give in to his mother’s demands for religious repentance, though, Stephen is forced to confront his fears in a dark hallucination. Stephen has already guessed that the Word is death, urging his corpse-chewing mother to just get it over and lay death at his feet. He breaks the spell of his fear of death, of his mother’s and his own, by rejecting the call to repentance. Only by subconsciously accepting his own mortality does he become free.

Why Not Both?

Often the solution to a hard binary choice is finding a third option. After completing each of the sections above, I had convinced myself that whichever theory I was currently working on was true. Of course, there are way more theories than just these two, each written and defended by Joyce scholars more clever and knowledgeable than myself. What one believes about any particular theory ultimately comes down to whether or not the reader thinks Joyce intended for the love lines to be included or not in “Scylla and Charybdis,” and if we’re being honest, the best answer we can come up with there is maybe. Both love and death are such dominant themes in Ulysses that it wouldn’t be all that hard to pin any particular question or symbol found in the novel to love, death or both. So I ask you, dear reader: why not both?

My main source of inspiration for this conclusion is a 1987 article by Jean Kimball found in James Joyce Quarterly that I would recommend checking out to get some excellent perspective on this controversy. Her interpretation of Stephen’s Word is just as I’ve suggested: it’s both love and death. Where English fails us, German picks up the slack. There’s a handy German word, liebestod, literally “love death,” meaning love consummated in death. It originated in Richard Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, but it serves our purposes here as the intersection of these universal concepts. Kimball writes that love and death are inextricably connected. We suffer death at the end of our lives because of an act of love on the part of our parents that resulted in our existence.

One way this duality is apparent is in Stephen’s recalled dreams during the first three episodes. His first dream is a dream of death - his mother’s ghoulish, corspe-chewing spectre. Towards the end of “Proteus,” Stephen recalls a second dream, this time a dream of love. It’s hazier than the lurid imagery of his death dream in “Telemachus,” but he recalls meeting Haroun al-Raschid and his comforting creamfruit on a street of harlots, which we find out is Leopold Bloom saving Stephen from himself in Dublin’s red light district. Both of the images of the spectral mother and Haroun al-Raschid recur throughout Ulysses. Not long after recalling his dream of Haroun al-Raschid, Stephen begins to contemplate his poem in a passage that includes the following line:

Bridebed, childbed, bed of death, ghostcandled.

These four words show the progression of a woman’s (his mother’s) life from her wedding night to her afterlife. The first two, bridebed and childbed, described moments of love, while the latter two, bed of death and ghostcandled, deal with her death. Love and death begin to meld together in Stephen’s mind. As Stephen toys with rhymes in his mind, he produces the phrase “allwombing tomb,” further solidifying the combination of a mother’s love and death as two sides of the same coin.

The image of Stephen’s mother dominates the passage in which his Word is mentioned in “Proteus” and “Circe,” so we must clarify: is she a symbol of love or death? In “Telemachus,” she appears in a dream as a ghoul and her death is discussed by Mulligan and Stephen at length. It’s the main point of conflict between the two in that episode, in fact: Mulligan’s description of her as beastly dead followed by refusal to apologize while doubling down on his cold, hyperborean approach to death. Stephen’s memories of his mother in her sickbed are all tinged with love, memories of her sense of humor and the song her sang at her request. Love is there, too, but in tandem with death.

In “Nestor,” mothers are portrayed as tender, maternal purveyors of life-sustaining love, the force allowing young men to grow into adults. Amor matris is powerful enough to keep them from being squashed like a snail. However, death lurks in the shadows. Thoughts of death plague Stephen throughout his lesson, particularly in his recitation of a riddle for his class in which he swaps “grandmother” in for “mother” to subconsciously dodge his grief. Love and death rolled together again. “Proteus” is heavy on death imagery, during which Stephen’s guilt is on display as he thinks, “I could not save her. Waters: bitter death: lost.” He also concludes that the one great goal of history Mr. Deasy spoke of is, in fact, death. Love’s bitter mystery is that we all die at the end.

Both the death aspect and love aspect of a mother are present in the ghost of Stephen’s mother when she appears to him in the brothel in “Circe.” She is ghoulish in appearance, but at first she speaks words of motherly love:

I pray for you in my other world. Get Dilly to make you that boiled rice every night after your brain work. Years and years I loved you, O my son, my firstborn, when you lay in my womb.

Once she loses patience with the now emboldened Stephen, she changes her tune fairly drastically, demanding repentance and warning of hellfire. She then transforms into a human-sized crab monster and tries to rip Stephen’s heart out. Man, this book really takes a turn. In any case, does she embody love? Yes. Does she embody death? Hell yes. What is the word known to all men? Why not both?

Further Reading:

Ellmann, R. (1986, Jun 15). Finally, the last word on 'Ulysses': the ideal text, and portable too. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://movies2.nytimes.com/books/00/01/09/specials/joyce-ideal.html

Finneran, R. (1996). "That Word Known to All Men" in "Ulysses": A Reconsideration. James Joyce Quarterly,33(4), 569-582. Retrieved fromhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/25473768

Fox, C. (1992). Absolutely: Redefining the Word Known to All Men. James Joyce Quarterly,29(4), 799-804. Retrieved fromhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/25485321

Gordon, J. (1990). Love in Bloom, by Stephen Dedalus. James Joyce Quarterly,27(2), 241-255. Retrieved fromhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/25485033

Herr, C. (1980). Theosophy, Guilt, and "That Word Known to All Men" in Joyce's "Ulysses". James Joyce Quarterly,18(1), 45-54. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25476336

Kimball, J. (1987). Love and Death in "Ulysses": "Work Known to All Men". James Joyce Quarterly,24(2), 143-160. Retrieved fromhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/25476793

Kimball, J. (1997). Odyssey of the psyche: Jungian patterns in Joyce’s Ulysses. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/y2bcb8oy

Sawyer, T. (1983). Stephen Dedalus' Word. James Joyce Quarterly,20(2), 201-208. Retrieved fromhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/25476504