The Chap that Writes like Synge

“Stephen had ment Synge in Paris, and the clash of their temperaments had produced heat but no light.” - Frank Budgen

Irish playwright John Millington Synge moves like a phantom through the pages of “Scylla and Charybdis”, Ulysses’ ninth episode. We get an allusion here, a namedrop there, but he never appears in person. Despite this absence, he is not spared the roasting that other Dublin literary types like Æ Russell, Richard Best and John Eglinton all must endure on the page. Synge just had the good fortune to not show up at the Library, I suppose. In the back half of “Scylla and Charybdis,” it’s Buck Mulligan who first shoe-horns Synge into the conversation:

“Buck Mulligan thought, puzzled:

—Shakespeare? he said. I seem to know the name.

A flying sunny smile rayed in his loose features.

—To be sure, he said, remembering brightly. The chap that writes like Synge.”

This comment, that Shakespeare is “the chap that writes like Synge” feels extremely out of pocket, so we can assume that the master mocker is at work again. Mulligan has so exquisitely crafted this burn that it requires deep knowledge of early twentieth century Irish theatre gossip to properly parse it. You see, Synge was taking the Dublin theatre scene by storm in 1904. His one-act plays Riders to the Sea and The Shadow of the Glen were major hits the previous year and enthusiastically promoted by the likes of W.B. Yeats and Lady Gregory. Yeats was especially effusive in his praise of Synge. Oliver St. John Gogarty, the real-life inspiration for Buck Mulligan, recalls being at a gathering with Yeats and several other friends, when Yeats suddenly exclaimed, “Aeschylus!” When questioned about his non sequitur, Yeats elaborated just as obscurely, “Synge, who is like Aeschylus,” and then described the ancient Greek dramatist as “The man who is like Synge!” Gogarty found this exchange positively absurd, and a variation on it wound up in Buck Mulligan’s mouth. So, this miniscule bit of mockery that mentions both Shakespeare and Synge is actually aimed at neither, but instead at an awkwardly ecstatic compliment from Yeats. Truly this is a feat of five-dimensional snark.

As Synge’s star was rising, James Joyce could barely get a publisher to look in his direction. Granted, Joyce was eleven years younger than Synge and at a different stage in his career, but that didn’t prevent a jealous rivalry from boiling over. Stephen Dedalus, like young James Joyce, holds a bitter antipathy for Synge, which Mulligan now attempts to wield as an instrument of torture, or possibly just mild annoyance:

“Joyfully he thrust message and envelope into a pocket but keened in a querulous brogue:

—It’s what I’m telling you, mister honey, it’s queer and sick we were, Haines and myself, the time himself brought it in. ’Twas murmur we did for a gallus potion would rouse a friar, I’m thinking, and he limp with leching. And we one hour and two hours and three hours in Connery’s sitting civil waiting for pints apiece.”

Mulligan continues on in this tone, dramatically recounting how he and Haines waited at The Ship while Stephen ghosted them in favor of the newsmen from the Evening Telegraph. The “querulous brogue” that Mulligan adopts here is meant as a parody of Synge’s dialogue. At Yeats’ insistence, Synge visited the Aran Islands in 1898, and then returned every summer until 1902. Synge learned to speak Irish during these years and had an ear for the linguistic particularities of the islanders. Riders to the Sea is set in the Aran Islands, and Synge strove to replicate Aran speech in his dialogue. Mulligan, in turn, is striving to recreate Synge’s recreation here, though of course with the intent to entertain Stephen. He succeeds in extracting a chuckle out of Stephen. Mulligan’s babble takes a dark turn as he invokes the name of Synge once more:

“—The tramper Synge is looking for you, he said, to murder you. He heard you pissed on his halldoor in Glasthule. He’s out in pampooties to murder you.”

Of course, in the next line we learn that Mulligan is the real phantom pisser, but Synge is convinced of Stephen’s guilt nonetheless. “Pampooties” are a type of leather shoe worn traditionally in the Aran Islands, so Mulligan finds more humor in Synge’s eccentricities and fascination with the Aran Islands. A more charitable observer might say that Synge spun his passion into brilliant art, but Mulligan takes the tried and true mean girl route of making fun of Synge’s shoes. Either way, Mulligan gets a good belly laugh out of goofing on his friend. Then, Stephen slips into a Paris flashback:

“Harsh gargoyle face that warred against me over our mess of hash of lights in rue Saint-André-des-Arts. In words of words for words, palabras. Oisin with Patrick. Faunman he met in Clamart woods, brandishing a winebottle. C’est vendredi saint! Murthering Irish. His image, wandering, he met. I mine. I met a fool i’the forest.”

“Harsh gargoyle face” certainly maintains that mean girl tone.

John Millington Synge

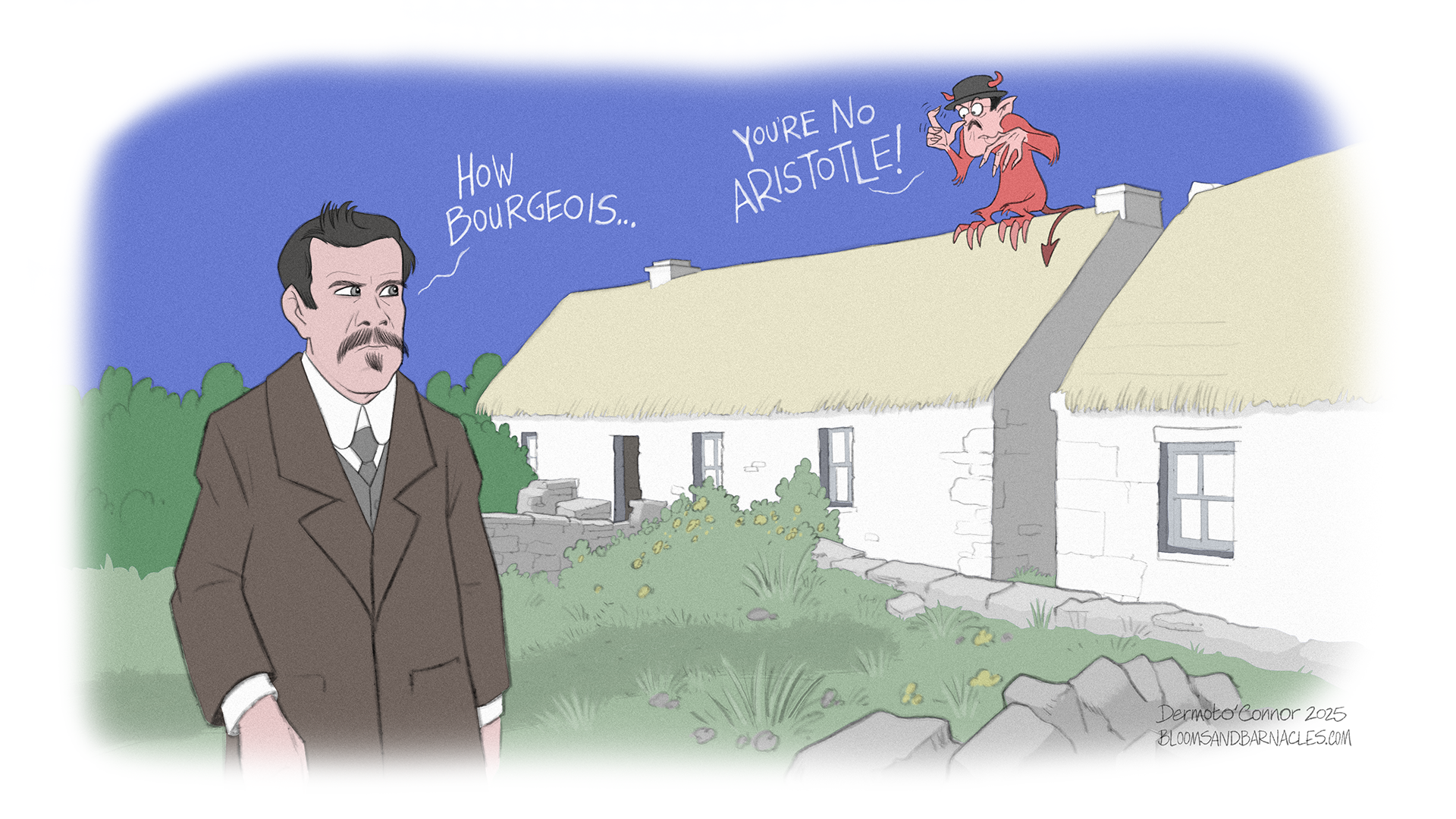

Stephen recalls doing battle with Synge in Paris over a generous serving of “hash of lights,” which Gifford and Seidman’s Ulysses Annotated interprets as another allusion to the ultra-cheap lung stew that Stephen recalls eating way back in “Proteus.” Stephen likens their meeting to that of Patrick and Oisín in the Fenian cycle of myths. In the story, Oisín encounters Patrick after living away in Tír na n’Óg for three hundred years. Upon returning home, Oisín finds all his loved ones long dead. He meets St. Patrick instead, who has arrived on Ireland’s shores with conversion in mind. Scholar John Hunt interprets this bit in “Scylla and Charybdis” as a meeting of the old pagan world and the new Christian paradigm. To make this parallel work in terms of Ulysses, we need to alter “Christianity” to “Aristotelianism.” Synge carries the banner of the old world, writing about the long-lost traditions of Aran islanders and the paganism that creeps just beneath the surface of their Catholicism. Stephen counters with his Jesuitical Aristotelian dogma, representing another clash of an ideological Scylla and Charybdis. Stephen in hindsight (and as we’ll see, Joyce writing with far more hindsight) recognizes that he and Synge have quite a bit in common, even though they fought like cats and dogs: “His image, wandering, he met. I mine.”

In real life, Joyce and Synge connected in Paris in 1903, and it truly seems like things could not have gone worse. Yeats described Synge to Joyce as a quiet man who never argued, but it seems like that was all he and Joyce did. Joyce’s jealousy was tweaked in 1902 when Yeats praised Synge’s plays as “Greek” (maybe even as good as Aeschylus!) — a level of praise no one was heaping on Joyce in those days. Synge made the grave mistake of letting Joyce read his manuscript of Riders to the Sea. Joyce used the opportunity to be incredibly petty, nitpicking the script until there was nothing left. He wrote to his brother Stanislaus:

“I am glad to say that ever since I read it, I have been riddling it mentally till it has [not] a sound spot. It is tragic about all the men that drowned in the islands: but thanks be to God, Synge isn’t an Aristotelian.”

Joyce made sure Synge knew all the ways in which his work fell short of Aristotle. He even dismissed the one-act play as not a play at all, merely a tragic poem, adding “No one-act play, no dwarf-drama can be a knockdown argument,” which Synge found quite insulting for some reason.

Did Synge once call Joyce bourgeois for wanting to go to a carnival? Yes. Did he also accuse Joyce of being obsessed with rules? Certainly. By all accounts, Synge did have an eccentric personality, but I’m willing to go out on a limb and say, based on the description of their meeting in Richard Ellmann’s biography of Joyce, their beef was entirely Joyce’s doing. Ellmann wrote that the two “parted amicably… respecting and disdaining each other.” Joyce takes the high road and acknowledges that they saw themselves in one another in Ulysses, but he drove poor Synge absolutely nuts in 1903.

There’s one more story shared by Mulligan that is only tenuously Synge-adjacent but worth exploring here while we’re at it. Stephen/Joyce annoyed more than just Synge in the Dublin theatre scene:

“He laughed, lolling a to and fro head, walking on, followed by Stephen: and mirthfully he told the shadows, souls of men:

—O, the night in the Camden hall when the daughters of Erin had to lift their skirts to step over you as you lay in your mulberrycoloured, multicoloured, multitudinous vomit!

—The most innocent son of Erin, Stephen said, for whom they ever lifted them.”

While I haven’t found any corroboration that either Gogarty or Joyce peed on Synge’s door, the story about Camden hall is based in truth, according to Ellmann’s biography. In 1904, Joyce had a habit of hanging around the National Theatre Society’s rehearsal space in Camden St. (hence Camden hall). He was “tolerated”, in Ellmann’s words, because he would sing for the performers during their breaks. On 20 June 1904, an actress tripped over something backstage that groaned at the impact with her shoe. She fled and upon returning with reinforcements, found a black-out drunk James Joyce lying on the ground. He did not take kindly to being awoken and tossed out into the street, and caused a ruckus, banging on the door demanding to be let back in. The Fay brothers, who ran the Theatre Society, opted not to open the door. Joyce retaliated with his most dangerous weapon: a rude poem. From Ellmann’s biography:

O, there are two brothers, the Fays,

Who are excellent players of plays,

And, needles to mention, all

Most unconventional,

Filling the world with amaze.

But I angered those brothers, the Fays,

Whose ways are conventional ways,

For I lay in my urine

While ladies so pure in

White petticoats ravished by gaze.

That’ll show ‘em.

In fairness, Joyce did eventually reconcile with the Fays, and W.G. Fay produced Joyce’s only play, Exiles, in 1926.

Sadly, any reconciliation Joyce might have had with Synge came too late, as the playwright died in 1909. After Joyce had left Dublin for good, he revisited the works of Synge, particularly Riders to the Sea. In 1907, Joyce set to work translating Riders into Italian. He shared Synge’s play with friends in Trieste, who were interested in producing the Italian-language version of the play. Joyce wrote to Synge’s estate requesting performance rights for the Italian version of Riders, though they never consented. It seems that the reception of Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World is partially what moved Joyce to change his tune. The 1907 debut of the play erupted into a riot at the Abbey theatre that spilled into the streets and had to be quelled by the Dublin Metropolitan Police. In the press, prominent Nationalists such as Arthur Griffith denounced the play as obscene filth and an insult to Ireland. The offending content? A brief mention of the women of Mayo in their nightgowns. Joyce was initially amused by Yeats’ public embarrassment over the affair, but his own struggles with obscenity charges caused him to re-evaluate Synge’s work. When it came time to publish Dubliners, Joyce sought out publisher George Roberts in part because he had published Playboy despite the obscenity accusations, though this relationship did not ultimately pan out the way Joyce hoped.

Joyce would go on to visit the Aran Islands with Nora and write about his experience once he was back in Trieste. In 1918, as he toiled away on “Scylla and Charybdis,” he even encouraged Nora to take a small role in a production of Riders to the Sea that was being staged in Zurich. He personally coached the actors on how to replicate Nora’s Galway accent and attempted to capture the music of the Aran speech that had so inspired Synge all those years ago.

Further Reading:

Budgen, F. (1972). James Joyce and the making of Ulysses, and other writings. London: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AMF2PZFZHI2WND8U

Ellmann, R. (1959). James Joyce. Oxford University Press.

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/vy6j4tk

Gogarty, O. (1937). As I was going down Sackville Street. London: Rich & Cowan Ltd. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/asiwasgoingdowns0000oliv/page/288/mode/2up

Kellogg, R. (1974). Scylla and Charybdis. In C. Hart & D. Hayman (eds.), James Joyce’s Ulysses: Critical essays (147-179). Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/wu2y7mg