Decoding Dedalus: Yogibogeybox in Dawson chambers.

This is a post in a series called Decoding Dedalus where I take a passage of Ulysses and break it down line by line.

The line below comes from “Scylla and Charybdis,” the ninth episode of Ulysses. It appears on page p.191-192 in my copy (1990 Vintage International). We’ll be looking at the passage that begins “Yogibogeybox in Dawson chambers.” and ends “For years in this fleshcase a shesoul dwelt.”

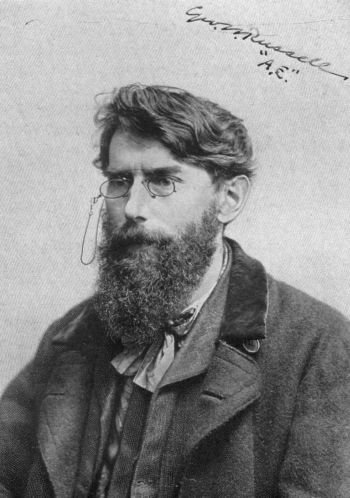

Stephen Dedalus is just getting into the juicy bits of his Shakespeare theory in “Scylla and Charybdis,” Ulysses’ ninth episode, when the mastermystic himself, George Æ Russell, decides he’s had enough. Æ is a busy man, don’t you know, and he is required elsewhere:

The mastermystic

“A tall figure in bearded homespun rose from shadow and unveiled its cooperative watch.

—I am afraid I am due at the Homestead.”

John Eglinton is disappointed by Æ’s sudden departure, but hopes that he will see Æ later that evening at George Moore’s home. There will be a gathering of Dublin’s literary lights, and surely Æ will be front and center. However, Æ demurely declines this invitation:

“—I don’t know if I can. Thursday. We have our meeting. If I can get away in time.”

Æ is referring to the Hermetic Society, of which he is the founder and leader. Our young Artist is utterly disgusted by this whole exchange, as he has conspicuously not been invited to Moore’s gathering. Stephen turns inward to self-soothe, giving his mind over to a second, scornful theosophical intrusion mocking Æ and his many acolytes:

“Yogibogeybox in Dawson chambers. Isis Unveiled. Their Pali book we tried to pawn. Crosslegged under an umbrel umbershoot he thrones an Aztec logos, functioning on astral levels, their oversoul, mahamahatma. The faithful hermetists await the light, ripe for chelaship, ringroundabout him. Louis H. Victory. T. Caulfield Irwin. Lotus ladies tend them i’the eyes, their pineal glands aglow. Filled with his god, he thrones, Buddh under plantain. Gulfer of souls, engulfer. Hesouls, shesouls, shoals of souls. Engulfed with wailing creecries, whirled, whirling, they bewail.”

Once again, Stephen reveals more than a passing knowledge of the inner working of the esoteric doctrines he derides in this passage. Let’s break it down line by line:

“Yogibogeybox in Dawson chambers.”

Not the yogibogeybox

This first phrase can be unraveled with a bit of good, old fashioned etymology. “Yogibogeybox” is a Joycean coinage; the Oxford English Dictionary notes only one usage of the phrase, and it’s in Ulysses. Scholar John Simpson gives a fantastic breakdown of the term on James Joyce Online Notes, which my summary here is based on. Much of Stephen’s commentary in this passage references the esoteric systems of theosophy and hermeticism, so right off the bat, we should understand that he does not take these people seriously at all.

The “box” in “yogibogeybox” is the most interesting piece of the puzzle to me, as it does not refer to a literal box, as some earlier commentaries on this passage conclude. This usage of “box” is pure Gogartian silliness. Stanislaus Joyce, James’ younger brother, wrote in his Dublin Diary that Oliver St. John Gogarty, the real-life model for Buck Mulligan, used “box” to refer to “any kind of public entertainment, or a hall where a society holds meetings for some purpose.” Stanislaus then offers a few examples. To Gogarty, the Hermetic Society’s rooms were a “ghost box,” a church was a “god box,” and a brothel was a “cunt box.” You get the idea. The Hermetic Society’s ghost box was originally Æ’s home, but as their membership grew, they took up residence in a room in Dawson Chambers.

Simpson tracks how the yogibogeybox evolved over various drafts of Ulysses. The first draft simply called it “their room.” In the 1918 draft, Joyce altered the opening phrase to “Their bogeybox in Dawson Chambers.” The Rosenbach manuscript from 1922 contains the phrase we all know and love, “Yogibogeybox in Dawson Chambers.”

“Isis Unveiled. Their Pali book we tried to pawn.”

Isis Unveiled, published in 1877, was the first major work of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, one of the founders of theosophy. Presumably the folks meeting in the yogibogeybox kept a copy on hand. “Pali” is the sacred language of Theravada Buddhism, so we can infer the topic of “their Pali book.”

The “we” in question in this line refers to Stephen and Mulligan (really Joyce and Gogarty) getting into shenanigans. I’ve looked high and low for a story of these two knuckleheads pawning a rare book stolen from the Hermetic Society and have come up empty. However, that doesn’t mean they didn’t get into any trouble. In his autobiography Mourning Became Mrs Spendlove, Gogarty recounts a memory of himself and Joyce getting day-drunk one random Sunday and raiding the Hermetic Society’s meeting space in Dawson St. Any story originating with Gogarty must be taken with the world’s largest grain of salt, as we’ll see. That being said, Gogarty tells how, in 1904, he and Joyce ransacked the unoccupied space, and did indeed see the bench upon which Æ enthroned himself during Society meetings.

During their drunken escapade, serendipity struck. A man by the name of George Roberts had stored a suitcase in the Society’s meeting room, expecting its contents to remain unmolested in the empty space. Roberts was a traveling salesman of ladies’ underwear, and the suitcase was full of samples. Gogarty decorated the room with the suitcase’s contents, including a disparaging display directed at John Eglinton. He alleges that Joyce insisted they take the remaining underwear to pawn. Upon realizing that no pawnbrokers would be open on a Sunday, he then pivoted to distributing it amongst their female friends as a goof. Stanislaus for his part disputes the details of this episode, specifically that his brother took the suitcase or distributed the underwear.

Æ was livid at this wanton act of vandalism, and he solely blamed Joyce. One version of the aftermath of this incident is that it caused Æ to exclude Joyce from his forthcoming book of poetry, New Songs. In Æ’s defense, he did publish three of Joyce's short stories in his Irish Homestead that summer. The stories weren’t quite what his readership was looking for, and as the complaints piled up, Æ informed the young Artist he simply couldn’t publish a fourth. Joyce would go on to include these stories in a collection that would ultimately become Dubliners. This is the unspoken undertone of the drama being re-enacted in this scene in “Scylla and Charybdis”, based so heavily on Joyce’s Dublin memories:

“—They say we are to have a literary surprise, the quaker librarian said, friendly and earnest. Mr Russell, rumour has it, is gathering together a sheaf of our younger poets’ verses. We are all looking forward anxiously.”

Stephen internally comments:

“See this. Remember.”

Boy, did he ever.

To return to Dubliners for a moment, Joyce’s collection of short stories turned out to be extremely difficult to publish, due in one part to controversial material and in another part to Joyce’s unwillingness to alter any of the controversial content. He was rejected by enough publishers that he decided to give one, Maunsel and Co., a second try. Maunsell accepted, but the editing process devolved into a long, drawn-out, and acrimonious fight between Joyce and Maunsell’s co-founder, George Roberts. Ultimately, negotiations broke down, and Roberts refused to publish Dubliners. Joyce retaliated by writing a scathing poem entitled “Gas from a Burner.” I haven’t found a source that directly connects Roberts’ rejection or harsh treatment of Joyce to the suitcase incident, but it does stand out in my mind and must have stood out in Roberts’ (if it happened at all). One reason I doubt Gogarty’s version is that in his telling, he remarks about turning off the gas burner in the Hermetic Society:

“The gas from the burner went out. We stumbled down the stairs, and into the street. To my amazement, I saw that Joyce was carrying the suitcase full of ladies’ underwear.”

This is a completely extraneous but provocative detail to the rest of Gogarty’s story, so I can’t help but see it as a red flag. It has to be a reference to Joyce’s poem, which he discusses at length in the same chapter. I’ve read multiple sources that detail the underwear-suitcase incident, but I have yet to read a source talking about the theft of a possibly rare or valuable Pali book. I wonder if there is a hidden pun in the Pali book line that I’m missing and can’t quite work out. Maybe they did steal the book, too, and it went unnoticed because we have all been telling and retelling the far more salacious story about the suitcase full of ladies’ drawers. Truly the crime of the century.

“Crosslegged under an umbrel umbershoot he thrones an Aztec logos, functioning on astral levels, their oversoul, mahamahatma. The faithful hermetists await the light, ripe for chelaship, ringroundabout him.”

Stephen now visualizes Æ conducting his mystical meeting. He imagines Æ, surrounded by his adoring acolytes, or “chelas” in theosophical lingo, vibing together on some far out, astral plane or whatever. Stephen finds the whole affair supremely silly.

I’ve complimented Stephen on his knowledge of Æ’s mysticism in the past, but here he mixes and matches terms taken from both hermeticism and theosophy. While he does refer to his strawmen as “hermetists” at their meeting of the Hermetic Society, the bulk of the terms employed to describe them here and elsewhere in this passage are taken from Blavatsky’s writings on theosophy. Stephen conflates the two esoteric systems in his derisive commentary, but I suppose that is an aspect of the derision. It’s all gobbledegook as far as Stephen is concerned and the main focus at this stage is being a hater towards Æ, not precision.

For the sake of our own precision, Hermeticism is a Western esoteric tradition, drawing on sources purporting to date back to Hellenic Egypt. Theosophy, on the other hand, syncretizes Eastern traditions such as Buddhism and Hinduism with spiritualism. Sanskrit terms like “mahamahatma” and “chela”, as well as a later reference to Buddhism, are taken from theosophical practices. Likewise, an interest in “astral levels” and “Aztec logos” would also be a Blavatskian preoccupation.

“Louis H. Victory.”

Louis H. Victory is the first of two names dropped in here without any context. Victory was a minor Dublin poet around the turn of the 20th century. I personally think he got tossed into this passage because of his 1896 book entitled The Higher Teachings of Shakespeare, which he dedicated to one George W. Russell. Victory’s approach to Shakespeare would have been in line with Æ’s “formless spiritual essences” philosophy of art. Thus spake Æ:

“Art has to reveal to us ideas, formless spiritual essences. The supreme question about a work of art is out of how deep a life does it spring. The painting of Gustave Moreau is the painting of ideas. The deepest poetry of Shelley, the words of Hamlet bring our minds into contact with the eternal wisdom, Plato’s world of ideas.”

Shakespearean Analysis

Victory opines in his book on “the profound ‘soul-wisdom’ with which Shakespeare’s pages are pregnant” and the necessity to “scrutinize the soul” of Shakespeare’s plays. I think this is exactly the kind of literary analysis that would drive Stephen/Joyce up a wall. On Hamlet, Victory declares:

“I am thoroughly convinced that if Hamlet’s teachings were allowed to take the place of those of the Bible, humanity should not suffer by the change.”

I think the nicest adjective I can use in response to Victory’s analysis is “debatable.” Many prominent and gifted writers of the era found themselves in Æ’s yogibogeybox, so why highlight Victory? I think the subtle accusation tossed by Stephen here is that Victory is a hack, and thus, Æ is a hack by association.

“T. Caulfield Irwin.”

Thomas Caulfield Irwin was also a Dublin poet from the late 19th century, well-known enough to be included in the Dictionary of Irish Biography (which Victory is not). Irwin had no known associations with Æ, theosophy, hermeticism or the like. He did, however, suffer from severe mental illness later in life, described by a “gentle mania” by a too-kind friend. His nextdoor neighbor, Celticist John O’Donovan, described Irwin a bit differently:

“I understand that the mad poet who is my next-door neighbour claims acquaintance with you. He says I am his enemy, and watch him through the thickness of the wall which divides our houses. He threatens in consequence to shoot me. One of us must leave. I have a houseful of books and children; he has an umbrella and a revolver…"

The reason for Irwin’s inclusion in this passage is unclear, though scholar Phillip Marcus argues that Irwin’s inclusion implies that Æ’s mystical society attracts madmen. I didn’t find anything in my sources to connect Irwin and Æ directly, but there was clearly some connection in Joyce’s mind. Personally, I think it is possible that at some point Æ complimented Irwin’s verse and did not extend the same open hand to Joyce, which would be enough for this very oblique slander in Ulysses.

“Lotus ladies tend them i’the eyes, their pineal glands aglow. Filled with his god, he thrones, Buddh under plantain.”

Gogarty notes in Mourning Became Mrs Spendlove that Joyce was annoyed that Æ’s acolytes were largely young women:

“The society intrigued Joyce; he could not get into it. The majority of its members were girls who worked in Pim’s, the large Quaker dry-goods store in which AE was an accountant. This was the society that George Moore and I visited years later to find AE astride a bench in a little room crowded with intense females, and in the process of digging up from the World Memory a Fifth Gospel.”

It’s clear from Gogarty’s narration that he also found Æ’s spiritual pursuits incredibly dorky. While it is always important to take Gogarty’s telling of a story with a fistful of salt, I think he brings up an important aspect of Joyce’s own psyche: the frustration of a shy young man who is desperate for female attention that feels just out of his grasp while at the same time convinced of his own genius. A volatile cocktail for sure. Worse still for this version of young Joyce, is that Æ, a shallow, two-bit mystic and a subpar poet, seems to be beating the girls off with a stick! The injustice!

This characteristic is exemplified by Stephen’s thoughts in “Proteus” of spying on the “virgin at Hodges Figgis’ window on Monday looking in for one of the alphabet books you were going to write,” too shy to talk to her and seemingly capable of only a “keen glance.” This brief fantasy gives way to outright lamentation:

“Touch me. Soft eyes. Soft soft soft hand. I am lonely here. O, touch me soon, now. What is that word known to all men? I am quiet here alone. Sad too. Touch, touch me.”

I think some of this youthful frustration lingered in Joyce’s mind as he wrote these passages and may be why he works so hard to make Æ seem like such a hack. It’s not just that Æ sucks, it’s that he sucks but girls like him anyway.

HPB

A second, less-Gogarty-influenced thought on this section is that Joyce is reacting to the elitism baked into theosophy. Prominent theosophists like Blavatsky and Annie Besant wrote overtly about the necessity of hierarchy in theosophy and rejected equality as an ideal, a belief captured in a previous theosophical intrusion in “Scylla and Charybdis”:

“The life esoteric is not for ordinary person. O.P. must work off bad karma first.”

Only those privileged with good enough karma could receive the messages from the mahatmas, or even know they existed. This qualification was physical as well as spiritual, requiring a powerful pineal gland, which Blavatsky believed to be the physiological manifestation of the third eye. Æ’s lofty position upon his throne and the bevvy of lotus ladies at his feet proves his place among the elect. He is Chosen and Stephen is anything but.

I think this is what Gogarty meant when said Joyce “could not get into it.” Joyce was excluded from the Hermetic Society, and more importantly, its opportunities for an up-and-coming artist. I don’t know that this was strictly due to social class as Joyce was a difficult character in general, but young Joyce was keenly aware that he lacked the money to be an artistic dilettante, as he viewed so many on the receiving end of his ire in Ulysses and beyond. Scholar Mark Morrison argues that all of Æ’s grand ideas about art and spiritualism might be boiled down to “simple acts of social prestige and exclusion,” and Joyce was outside looking in. This is a critique that Joyce held against the Irish Literary Revival more broadly and will continue to be developed as Ulysses proceeds.

“Gulfer of souls, engulfer. Hesouls, shesouls, shoals of souls. Engulfed with wailing creecries, whirled, whirling, they bewail.”

“In quintessential triviality

For years in this fleshcase a shesoul dwelt.”

Stephen imagines a wailing maelstrom of souls, whirling at the behest of the Gulfer of Souls himself, Æ, in a final Charybdian image to close out this theosophical-hermetic intrusion. It calls to mind the souls of the damned buffeting Francesca and Paolo in Dante’s Inferno, as referenced by Stephen himself back in “Aeolus,” hinting at a grim fate for those who get pulled into Æ’s nonsensical whirlwind. This vision of Charybdis is punctuated by a bit of verse based on the poem “Soul-Perturbing Mimicry” by the one and only Louis H. Victory. The original lines read:

“In quintessential triviality

Of flesh, for four fleet years, a she-soul dwelt.”

Joyce alters “four” to “for,” as the original poem is about the death of a child. Mocking some things may be too much, even for Joyce.

Further Reading:

Ellmann, R. (1959). James Joyce. Oxford University Press.

Igoe, V. (2016). The real people of Joyce’s Ulysses: A biographical guide. University College Dublin Press.

Ito, E. (2003). Mediterranean Joyce Meditates on Buddha. Language and Culture, No.5 (Center for Language and Culture Education and Research, Iwate Prefectural University), 53-64. Retrieved from http://p-www.iwate-pu.ac.jp/~acro-ito/Joycean_Essays/MJMonBuddha.html

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/vy6j4tk

Gogarty, O. (1948). Mourning became Mrs. Spendlove and other portraits grave and gay. New York: Creative Age Press.

Jenkins, R. (1969). THEOSOPHY IN “SCYLLA AND CHARYBDIS.” Modern Fiction Studies, 15(1), 35–48. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26279201

Lunney, L. (Oct 2009). Irwin, Thomas Caulfield. In Dictionary of Irish Biography. Retrieved from https://www.dib.ie/biography/irwin-thomas-caulfield-a4226

Marcus, P. L. (1973). Notes on Irish Elements in “Scylla and Charybdis.” James Joyce Quarterly, 10(3), 312–320. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25487059

Morrisson, M. (2009). "Their Pineal Glands Aglow": Theosophical Physiology in "Ulysses". James Joyce Quarterly, 46(3/4), 509-527. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20789626

Simpson, J. The mystic yogibogeybox. James Joyce Online Notes. Retrieved from https://www.jjon.org/joyce-s-words/yogibogeybox