U.P: Up

“Of course, there is the possibility that it means nothing whatever; then Denis Breen is projecting his own mental disturbances on an essential blank.” - Robert Adams, Surface and Symbol

Present-day Westmoreland St.

Bloom’s route to lunch in Ulysses’ eighth episode, “Lestrygonians”, is littered with obstacles. After dodging the Hely’s sandwichmen and crossing Westmoreland St., Bloom bumps into an old friend: Josie Breen, née Powell. As we will learn much later in Ulysses, Mrs. Breen is an old flame of Bloom’s from the pre-Molly days. They exchange some small talk, but when Bloom asks after her “lord and master,” the conversation shifts in tone:

“—O, don’t be talking! she said. He’s a caution to rattlesnakes. He’s in there now with his lawbooks finding out the law of libel. He has me heartscalded. Wait till I show you.”

Mrs. Breen hands Bloom a postcard that her husband, Denis, received that morning. It reads, succinctly but cryptically, “U.P.: up.” It’s enough to send ol’ Denis into a tizzy. He’s been running around the city with a stack of law books hoping to sue the libelous sender for a jaw-dropping £10,000. When Bloom meets Mrs. Breen, Mr. Breen is seeking the services of John Henry Menton, Bloom’s old rival who we met back in “Hades”. We learn from Mrs. Breen that her husband hasn’t been doing well lately in general. Just last night he woke having a nightmare about the ace of spades walking up the stairs. Mrs. Breen blames the new moon for her husband’s disturbance, but her “shabby genteel” appearance hints that the once prosperous couple are now in decline.

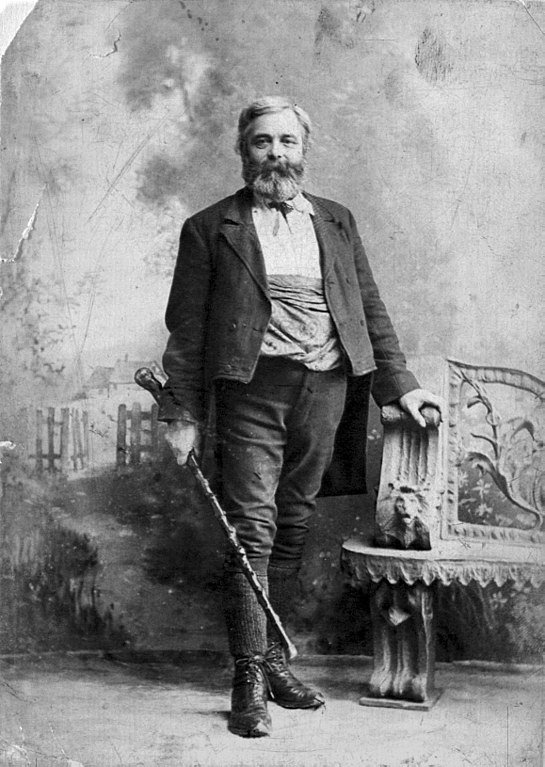

Mr. Breen

During this brief encounter, we do not learn the meaning of the cryptic postcard that has so scandalized Mr. Breen, nor do we learn who sent it. The initials U.P. repeat throughout Ulysses, and though the postcard writer’s identity is guessed at, we never definitively learn its source. Bloom, for his part, takes a stab at the latter question:

“U. p: up. I’ll take my oath that’s Alf Bergan or Richie Goulding. Wrote it for a lark in the Scotch house I bet anything.”

But what does it all mean? Joyce hid lots of mysteries and clues to their answers in Ulysses. Let’s see what we can glean about the true meaning of the U.P.: up postcard.

An Empty Threat

The first thing to know about U.P.: up is that it’s not unique to Ulysses. This once common expression has fallen out of use in the 21st century, but a reader in the early 1920’s would have easily recognized it. In common use, it meant “it’s all up,” or “you’re done for.” The “U.P.” part is just spelling the word “up”. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the expression as meaning, “over, finished, beyond remedy.” It was often used to announce a death, as it is used in Oliver Twist and many other 19th century works of literature. Most importantly for our purposes, it was used in this sense by James Joyce. In a 1928 letter to French writer Valery Larbaud, Joyce wrote:

“Apparently I have completely overworked myself and if I don’t get back sight to read it is all U-P up.”

Scholar John Simpson, in a post on James Joyce Online Notes, provides many, many examples of U.P.: up in use in that era. Simpson favors this “conservative” interpretation, as does scholar Sam Slote in his 2022 Annotations to James Joyce’s Ulysses. It makes sense. Looking at this scene more broadly, a sense of unfortunate finality lends a wistful nostalgia to Bloom and Mrs. Breen’s conversation, remembering bygone days that are now U.P.: up:

“Josie Powell that was. In Luke Doyle’s long ago. Dolphin’s Barn, the charades. U. p: up.”

Furthermore, Bloom’s memory of the last time he had sex with Molly is interrupted by Mrs. Breen’s initial greeting. The Blooms’ intimate life, for the present anyway, is utterly, positively U.P: up:

“Swish and soft flop her stays made on the bed. Always warm from her. Always liked to let her self out. Sitting there after till near two taking out her hairpins. Milly tucked up in beddyhouse. Happy. Happy. That was the night…”

It also connects fairly effortlessly to Breen’s vision of the ace of spades, a common symbol of death or ill fortune. It’s appropriate that the ace of spades was coming “up” the stairs in the dream as well. The implication of the postcard, then, is that Denis Breen is a dead man. Some unnamed threat is coming his way, so he better watch out. It’s easy to see how he would find this anonymous threat libelous.

Alright, case closed, I guess.

Well, not so fast.

There are plenty of other scholars out there with some interesting interpretations of “U.P.: up” that we should at least consider, even if we ultimately end up agreeing with Simpson and Slote. In my opinion, the common use of U.P.: up is just a starting point. Joyce loved wordplay and hidden codes. He also had a penchant for using initials to ascribe subtle, underlying meaning to characters and concepts, so why not here, too? It’s best to operate from the assumption that there is some kernel of a larger meaning to U.P.: up.

With that in mind, let’s take a look at a few more theories before we hang up our hats for the day.

You Pee Up

It’s no surprise that some scholars have assumed a more excretory meaning to U.P.: up – the postcard is meant to read, “You pee up.” Joyce saw value in the artistic use of filth and obscenity in his work, even going so far as to say that he believed the artist’s purpose is to act as a conduit for the filth of society. He was even called out for his “cloacal obsession” by H.G. Wells.

What exactly does it mean to “pee up”, though? The first thought that springs to my mind is that Mr. Breen pees while he has an erection, an experience that I’m told, while unpleasant, is not outside the realm of possibility. I don’t know if this is libelous to the tune of £10,000, though. The other image that springs to mind is Larry David “peeing up” in Curb Your Enthusiasm. Since Larry accidentally pees on a portrait of Jesus and hides his crime, I suppose this would be a more scandalous accusation. I don’t think Joyce watched a lot of Curb, though. In any case, accusing someone of peeing up, while weird, doesn’t seem particularly libelous.

So, what do the scholars say? In the book Surface and Symbol, Robert Adams suggests five meanings for U.P.: up, three of which are derogatory remarks about Mr. Breen’s body. Adams wrote that the postcard could mean “you urinate,” which would mean “you’re no good” or that Mr. Breen puts his finger up his anus. Both of these seem like big stretches, particularly the second one. Adams also suggests that the word “up” accuses Mr. Breen of not being able to “get it up” anymore, of erectile dysfunction. In this case, the expression is just spelling the word “up.” This one works a little better, reminding Bloom that his sex life is U.P.: up as well. Even if the postcard writer didn’t have this meaning in mind, it would explain why it sticks in Bloom’s thoughts throughout the day. Scholar Richard Ellmann thought that “U.P.” could be code for Ulysses and Penelope, further reinforcing this interpretation.

Ellmann, in his book Ulysses on the Liffey, takes this basic idea and runs with it. He believed that the postcard is implying that Breen ejaculates urine rather than semen, which comes out of left field for me. I’m not sure that Denis Breen would pull that meaning from four letters on a postcard, or that it would be a go-to allegation from his tormentors. Ellmann’s idea is rooted in the writings of the Nolan himself, Giordano Bruno, who reasoned that opposites are merely different aspects of a single concept rather than the end points of a linear continuum. Ellmann explains:

“Hot is opposite of cold, but they are both aspects of a single principle of heat…. The deepest night is the beginning of dawn.”

Running with this train of thought, Ellmann argues that corruption and generation maintain a similar relationship, two sides of the same coin. An example of this is Stephen’s description of a submerged corpse in “Proteus”:

“Bag of corpsegas sopping in foul brine. A quiver of minnows, fat of a spongy titbit, flash through the slits of his buttoned trouserfly.”

Stephen Pees Up

This corpse, a corrupted form of a man, experiences an ejaculation of sorts in the form of a quiver of minnows, an attempted generative act by a corrupted form. Denis Breen ejaculating urine occupies the same philosophical niche. His ejaculation results in a waste product (urine) rather than a generative one (semen). This interpretation, though odd, does fit in with the larger themes of Ulysses.

These obscene interpretations raise a question: if the Breens had inferred a sexual or other bodily libel in the postcard, why would Mrs. Breen show it to Bloom in the first place? For some commenters, this incongruity rules out an excretory interpretation of U.P.: up. I don’t think this is an unsolvable problem, though. Perhaps Mrs. Breen isn’t aware of an obscene connotation and thinks her husband has simply gone bananas. She then shows Bloom the card to prove her point - that it’s nothing. Even if Mrs. Breen had an inkling of a fouler meaning, it’s not unthinkable to me that she would show Bloom a postcard with an inappropriate message on it. They were once close, now polite, but she is at her wits end. She trusts Bloom well enough to reach out for commiseration if nothing more.

You, Protestant!

If all this dirty talk is too much for you, then let’s talk about a religious interpretation for U.P.:up. This theory is argued in the book Joyce's Ghosts: Ireland, Modernism, and Memory by scholar Luke Gibbons. In this interpretation, U.P.:up is not body shaming or a death threat against Mr. Breen but instead impugns his piety as a Roman Catholic.

In “Lestrygonians”, after Bloom and Mrs. Breen part ways, Bloom hypothesizes who might have written the offending postcard:

“U. p: up. I’ll take my oath that’s Alf Bergan or Richie Goulding. Wrote it for a lark in the Scotch house I bet anything.”

We meet both Alf and Richie in later episodes, but since Richie doesn’t behave suspiciously over dinner in “Sirens”, we’ll focus in on L’il Alf Bergan. The Breens re-emerge in “Cyclops” passing Barney Kiernans’ pub, which is a stone’s throw from the Green Street Courthouse:

Green Street Courthouse

“Little Alf Bergan popped in round the door and hid behind Barney’s snug, squeezed up with the laughing…. I didn’t know what was up and Alf kept making signs out of the door. And begob what was it only that bloody old pantaloon Denis Breen in his bathslippers with two bloody big books tucked under his oxter and the wife hotfoot after him, unfortunate wretched woman, trotting like a poodle. I thought Alf would split.

—Look at him, says he. Breen. He’s traipsing all round Dublin with a postcard someone sent him with U. p: up on it to take a li...

And he doubled up.”

So, Alf Bergan knows the contents of the postcard and its effect on Breen. There’s also the tantalizing line, “And he doubled up,” since a doubled “up” is exactly what the postcard-writer wrote. We also learn that Alf and friends are more than willing to mess with the Breens just for the hell of it:

“—Breen, says Alf. He was in John Henry Menton’s and then he went round to Collis and Ward’s and then Tom Rochford met him and sent him round to the subsheriff’s for a lark. O God, I’ve a pain laughing. U. p: up. The long fellow gave him an eye as good as a process and now the bloody old lunatic is gone round to Green street to look for a G man.”

Notably, Breen has been into Collis and Ward, where Richie Goulding, “the drunken little costdrawer” and Stephen’s uncle, is an accountant, so Richie may at least be aware of the prank. While he used to paint the town red with Ignatius Gallaher, but there doesn’t seem to be any more evidence of his involvement in the U.P.:up affair. Alf and the pub patrons, on the other hand, are more than a little interested in the Breens, and they clearly hold them in contempt. Mr. Breen’s mental illness is the day’s entertainment, and they deride Mrs. Breen as an “unfortunate wretched woman, trotting like a poodle.” The more empathetic Bloom tries to defend his old friend, but the “Cyclops” barflies are not having it:

“And Bloom explaining he meant on account of it being cruel for the wife having to go round after the old stuttering fool. Cruelty to animals so it is to let that bloody povertystricken Breen out on grass with his beard out tripping him, bringing down the rain. And she with her nose cockahoop after she married him because a cousin of his old fellow's was pewopener to the pope.”

Though the Breens have fallen on hard times, it seems they once enjoyed higher status. At least in the estimation of the anonymous “Cyclops” narrator, Josie Powell married Denis Breen for his family connections in the Church. The pub patrons so begrudge her attempt at social climbing that they are amused at her fall as much as they are amused at Denis Breen’s madness. Given this, an implication of impiousness would be a major offense to the Breens.

Michael Cusack

In his book, Gibbons deep-dives into the class-driven conflicts between Catholics and Protestants of this era. In an extremely small nutshell, the Protestant Ascendancy held most political and economic power in Irish society to the exclusion of Catholics. One real-world manifestation of this dynamic involves Gaelic Athletic Association founder Michael Cusack, the real-world model for the brutish Citizen in “Cyclops”. In the 1880’s, Cusack’s friend, A. Morrison-Miller, founded the Caledonian Games Society, a group to play Scottish sports and a parallel institution to the GAA. Morrison-Miller ended up being expelled from his own group after a Presbyterian faction gained power within the CGS. Cusack was furious on his friend’s behalf, and wrote a column denouncing this turn of events in The Celtic Times in 1887 under the headline “U.P.: Up.” In his column, Cusack definitely used “U.P.: UP” in the sense of dead or finished; the final line reads:

“The C.G.S. has died a sudden and unprovided death. R.I.P.”

He also alluded to the role of the United Presbyterians in the expulsion of Morrison-Miller. So, the CGS is U.P.: Up because of the incursion of the U.P.’s. Since it’s Cusack using U.P. in this sense, perhaps the Citizen would as well, and by extension, his cohorts in the pub would be familiar with the double meaning. And the postcard? Accusing a man like Mr. Breen, who has staked his reputation on his Catholic piety, of being a U.P. or an apostate, would be quite inflammatory. Not only would this be a great way to mess with someone Alf and co., sneer at, but Breen could also reasonably take it as damaging his reputation. There’s further evidence within the text of Ulysses that religious libel might be the subtext of Mr. Breen’s mysterious postcard. Joe in Barney Kiernan’s jokes:

“—Was it you did it, Alf? says Joe. The truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, so help you Jimmy Johnson.”

Jimmy Johnson was a Scottish Evangelical Presbyterian preacher.

Backing up to “Lestrygonians”, Bloom’s initial hypothesis is that Alf Bergan or Richie Goulding “wrote it for a lark in the Scotch house.” The Scotch House was the name of a Dublin pub, but Gibbons views this as a hint at a Scottish element to the postcard. Joyce also drops this possible clue in the next paragraph:

“[Bloom] passed the Irish Times. There might be other answers lying there.”

On the surface, Bloom is pondering whether or not he might have more letters from “smart lady typists” awaiting him, but with a few more details, we discover an interesting subtext. It’s in this paragraph, too, that Bloom thinks about using code in his smart lady typist letters, so we are free to become codebreakers as well. In the next paragraph, Bloom thinks:

“Best paper by long chalks for a small ad. Got the provinces now. Cook and general, exc. cuisine, housemaid kept. Wanted live man for spirit counter. Resp. girl (R.C.) wishes to hear of post in fruit or pork shop. James Carlisle made that.”

According to Gibbons, what Bloom is alluding to here is the Irish Times’ business model of covering news in a way that supports the Protestant Ascendancy while simultaneously running ads that appeal to a provincial Catholic readership, thus increasing revenue from both groups while continuing to push the establishment line. “Resp. girl (R.C.)” means “respectable girl (Roman Catholic).” Bloom notes that this was the strategy of “James Carlisle.” James (who was actually a “Carlyle” rather than a “Carlisle”) was managing director of the Irish Times and was credited with its success in this era, as this passage implies. Gibbons writes that Cusack blamed the Scottish-born Carlyle for the ouster of Morrison-Miller from the CGS. Therefore, when Bloom says there might be other answers lying in the Irish Times, it’s an oblique reference to the incursion of U.P., or United Presbyterians, into Irish Catholic life. Answers to the U.P.:up conundrum lie with the Scots.

If this is the true meaning of “U.P.: up”, I think it makes the men in Barney Kiernan’s very strong suspects as the postcard writers, though perhaps not beyond a reasonable doubt. The Citizen, our stand-in for Cusack, refers to Breen as a “half and half,” an emasculating insult, and a “pishogue,” meaning as J.J. O’Molloy says, Breen is not compos mentis. If it the Citizen had any role in harassing Breen, he knows how to play it cool better than Alf and the boys, who carry themselves like overgrown schoolboys (though they seem completely unconcerned about being served with a lawsuit). None of this rules out a simple, empty threat or a sophomoric insult aimed at the distinctly odd Denis Breen. If they bear some personal animus against Breen, especially for loud and insincere piety, accusing him of apostasy as a prank feels logical to me if they know that will really get his goat. While I think there is insufficient evidence to truly know if any of these men wrote the postcard, if they do know the postcard-writer’s identity, there are no informers in the bunch.

A False Messenger

Before we conclude, let’s follow one, last strange rabbit trail mapped out by scholar James T. Ramey. For clues to this theory, we must look to Joyce’s schemata of correspondences and to Ulysses’ antepenultimate episode, “Eumaeus.”

In the schema, or outline of correspondences, that Joyce sent to his friend Carlo Linati in 1920, he lists “Ulysses Pseudangelos”among the characters who at appear in “Eumaeus”. This mysterious figure is connected symbolically to sailors, and by extension, Sailor W.B. Murphy, who Bloom and Stephen meet in the cabman’s shelter. In case you thought the allusion to Michael Cusack’s column in the last theory was a bit obscure, “Ulysses Pseudangelos” is a reference to a Greek tragedy called Odysseus Pseudangelos, whose text has been lost and whose author is unknown. The only reason it’s remembered at all is through a fleeting reference in Aristotle’s Poetics. The title translates as “Odysseus, Disguised as a Messenger” or “Odysseus the False Messenger”, and it is believed to tell the story of Odysseus, disguised as a beggar, meeting Telemachus in the hut of Eumaeus the swineherd.

How do we get from a lost Greek play to Westmoreland St. in 1904? To start with, Ulysses Pseudangelos’ initials appear on Denis Breen’s anonymous postcard. Ramey makes a point of noting that ancient Greek oracles like to issue warnings alongside cryptic advice on how to escape the predicted danger. With this in mind, we can imagine Breen as just such an oracle for Bloom. Afterall, Breen dreamed of the ace of spades the night before, a portent of terrible calamity. This foreboding image is delivered to Bloom alongside a postcard that reveals the direction of escape: U.P.: up. Ramey conceives this shadowy U.P., Ulysses Pseudangelos, as “an immortal literary being wandering through the novel in disguise.” “U.P.” is his initials, and “up” is his message. Ramey thinks since U.P.’s human form, Sailor Murphy, arrived on the Rosevean at 11 a.m. that morning, he would have ample time to deliver the postcard to Breen in the late morning. But isn’t he a false messenger? Ramey thinks the falseness of the message is that it appears as a libelous attack on Breen when, in truth, it’s a warning for Bloom.

And what of this calamity? In Ramey’s interpretation, it manifests in the form of the impenetrable dark spot that concludes “Ithaca” and Bloom’s on-page presence in the novel. In this sequence, Bloom and Sinbad (a symbolic Sailor Murphy and thus, Ulysses Pseudangelos) must grip the roc’s leg to fly out of the dark spot. The final question of “Ithaca” is “Where?” U.P. has already answered the question back in “Lestrygonians”: Up.

I don’t read Ramey’s interpretation as the One True solution to U.P.: up, but I like it as one solution among several. There’s a danger of going too esoteric trying to unravel this puzzle, but there’s also a danger of remaining too conservative. Joyce plays with initials and multilayered meanings frequently throughout Ulysses, so why should U.P.: up be the exception to the established pattern? The phrase is repeated throughout the book, so it is important enough for Joyce to embed multiple, shifting uses within it. The simplicity of a secret message composed of two letters, already in usage as a common expression, that can take on overlapping meanings depending on context is consistent with Joyce’s artistic style. Look no further than the multilayered meanings found in the initial HCE and ALP in Finnegans Wake. Once we readers realize this, the only way is… you get the idea.

Further Reading:

Adams, R. M. (1962). Surface and Symbol: The Consistency of James Joyce’s Ulysses. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bergman, G. The anonymous libeller of Denis Breen. James Joyce Online Notes. Retrieved from: https://www.jjon.org/jioyce-s-people/breen

Cecconi, E. (2007). Who chose this face for me?: Joyce’s creation of secondary characters in Ulysses. Peter Lang.

Ellmann, R. (1972). Ulysses on the Liffey. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.65767/2015.65767.Ulysses-On-The-Liffey_djvu.txt

Gibbons, L. (2015). Joyce's Ghosts: Ireland, Modernism, and Memory. United States: University of Chicago Press. Retrieved from https://www.google.ie/books/edition/Joyce_s_Ghosts/ko7JCgAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/vy6j4tk

Ramey, J., & Ramey, J. T. (2007). Intertextual Metempsychosis in Ulysses: Murphy, Sinbad, and the “U.P.: up” Postcard. James Joyce Quarterly, 45(1), 97–114. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30244719

Simpson, J. Carlyle one, Carlisle nil. James Joyce Online Notes. Retrieved from: https://www.jjon.org/jioyce-s-people/carlyle

Simpson, J. U.P: up and away. James Joyce Online Notes. Retrieved from: https://www.jjon.org/joyce-s-allusions/up-up