Kino's & Hely's: Two Ads in Lestrygonians

“In using advertisements to represent Ulysses, then, Joyce is intentionally degrading the novel, drawing it into the muck of popular culture for comic effect. A trouser advertisement in a rowboat: This is the language of Ulysses!” - Daniel Gunn

Leopold Bloom, adman extraordinaire, can’t help but notice the dozens of ads he passes throughout the day in Ulysses. Some delight Bloom so thoroughly that what seems like innocuous visual noise takes on important symbolic resonance throughout the whole of the novel. Others need a punch up to meet Bloom’s exacting standards. Let’s take a look at two in particular that he passes on his journey in “Lestrygonians”, Ulysses’ eighth episode: Kino’s 11/- trousers and Hely’s.

Leopold Bloom’s Philosophy of Advertising

Luckily for us readers, Bloom lays out his philosophy of advertising in the “Ithaca” episode in response to the question, “What also stimulated him in his cogitations?” An ideal ad should have the following qualities:

“the infinite possibilities hitherto unexploited of the modern art of advertisement if condensed in triliteral monoideal symbols, vertically of maximum visibility (divined), horizontally of maximum legibility (deciphered) and of magnetising efficacy to arrest involuntary attention, to interest, to convince, to decide.”

So, it should be easy to see and read, and “arrest involuntary attention.” Bloom’s primary example of this is Kino’s 11/- (read as “eleven shilling”) trousers:

“Such as?

K. 11. Kino’s 11/— Trousers.”

He also lists out several unsuccessful ads, among them Plumtree’s Potted Meat (which we’ve covered at length here).

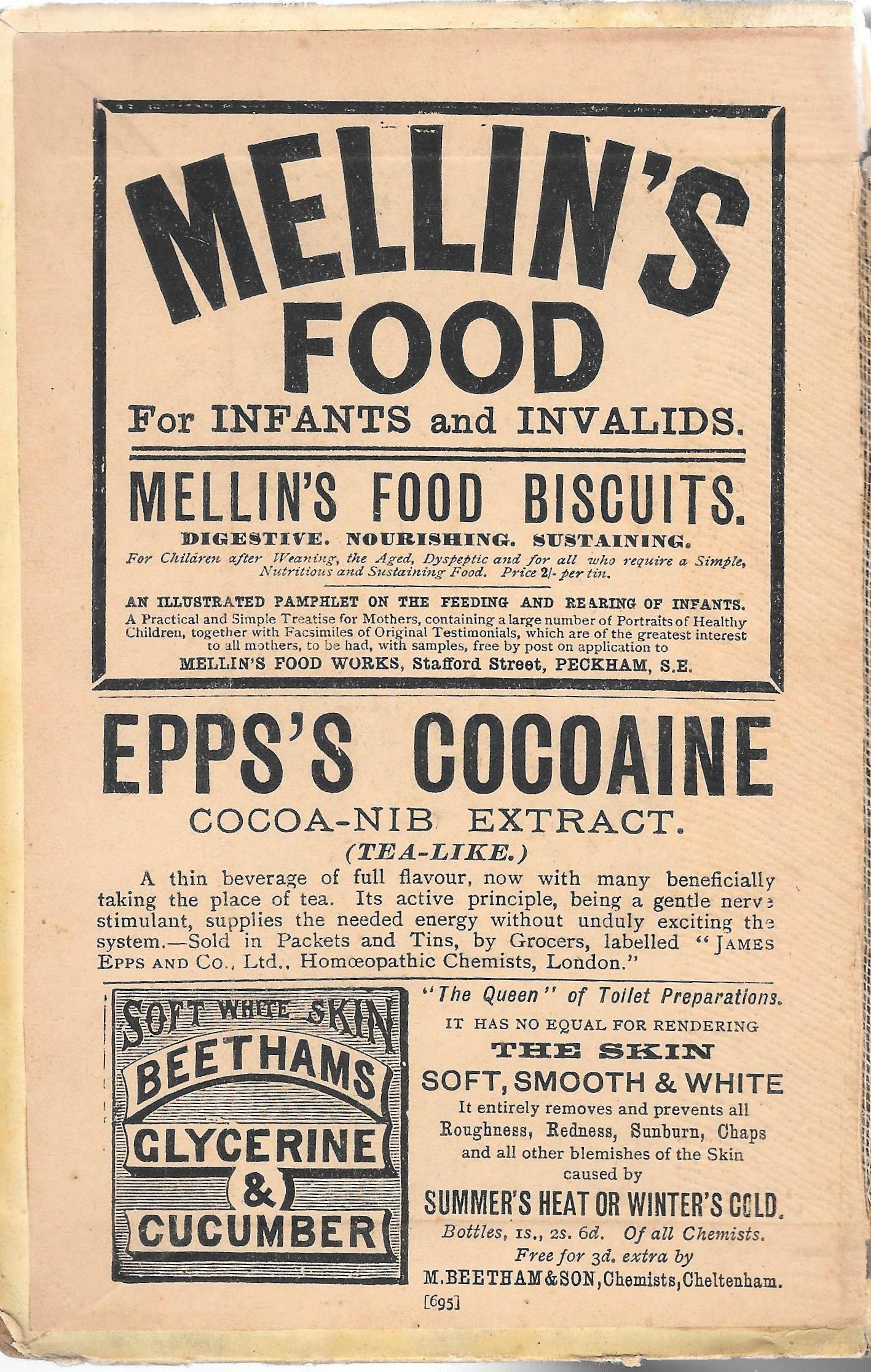

Ads from 1890; Scanned image and text by Simon Cooke. (Image Source)

We’ll return to Kino’s in a moment, but let’s consider Bloom’s ideas a bit further. These principles seem pretty basic, to be honest. However, at the turn of the twentieth century, they were fairly innovative. Victorian ads were often packed with tiny, expository text and sometimes no image at all. It was thought during this era that ads relied on appeals to reason, stating the case for why their product should be chosen over a competitor’s, listing information like prices and hard evidence of the product’s efficacy. Bloom’s candle ad copy from “Ithaca” is an example of this kind of ad:

“Look at this long candle. Calculate when it burns out and you receive gratis 1 pair of our special non-compo boots, guaranteed 1 candle power. Address: Barclay and Cook, 18 Talbot street.”

This is a nineteenth century sales tactic, though, and Bloom is a twentieth century man. Bloom is living in a time of transition into a new age of advertising, if only he can get the conservative old men he works for to listen! He can’t help but feel that a more modern approach to advertising has not been “hitherto exploited” by Dublin’s ad men.

Leopold Bloom at work

James Joyce shared Bloom’s passion for ads and naturally was well-read on the subject. Scholar Sabrina Alonso points out Joyce’s interest in Advertising, Or the Art of Making Known, a 1910 book by Howard Bridgewater that focuses on then-current psychological concepts and how they could be used to advertise. Bridgewater’s approach focused more on playing to “human volition,” and relying on emotional appeals rather than rational appeals.

In Ulysses, the Plumtree’s Potted Meat ad is a great example of this tactic, tying its potted meat to the idea of domestic bliss. When you buy Plumtree’s Potted Meat, you’re really buying that emotion, perhaps a desire for future bliss or even the nostalgia for bygone days of bliss. There is no logical reason to purchase Plumtree’s Potted Meat. Bloom doesn’t like the Plumtree’s ad campaign, but this is due to his own emotional baggage. Poor Plumtree’s gets listed under “such as never” in his assessment of advertising in “Ithaca”.

Joyce felt that typical advertising posters were too static to be really effective. In keeping with this idea, many of the ads that catch Bloom’s eye in “Lestrygonians” are in motion. The Elijah throwaway is thrust into his hand by a proselytizer in motion, the Kino’s rowboat bobs on the Liffey, and the Hely’s sandwichmen trundle their way down Westmoreland St. Their “efficacy to arrest involuntary attention” is strengthened by their motion. They are maximally visible and legible, though Bloom approves of Kino’s ad placement more than the Hely’s sandwichmen, who are maximally visible but somewhat less legible when they fall out of sync with one another. Many of these ads also promise renewal or transformation, both in a religious sense (Elijah) and in a faux-religious sense (Plumtree’s Potted Meat). Kino’s and Hely’s make less explicit claims, but perhaps a passerby can fill in the gaps with their own imagination about how a nice pair of slacks or a top-notch set of stationery could improve their life.

Finally, we must keep in mind Joyce’s sense of humor when approaching these ads. Humor is a common tactic in advertising as it’s a good way to draw people in and make the ad sticky. Such ad slogans can be repeated infinitely as shorthand for larger concepts, a low-brow method to draw our attention to higher concepts. Consider the way Bloom drops the Pears Soap slogan into his stream of consciousness while talking to Bantam Lyons in “Lotus Eaters” - “Good morning, have you used Pears’ soap?” It’s a humorous way for Bloom to propose a solution to Bantam’s poor hygiene, but it can also communicate Bloom’s desire to have his own bath at the Turkish baths with the lemon soap he’s just bought. It also taps into period anxieties about cleanliness and class. Finally, it can also hint at metaphoric moral “dirt” caused by Bloom’s epistolary affair with Martha. There’s a lot in that silly Pears slogan. (You can read more about this here.) The ads that Bloom encounters in “Lestrygonians” also embody this sense of ludicrousness, even as they transform into literary motifs in the pages of Ulysses. “Elijah is Coming” only seems like a straightforward religious decree until you learn about the real-life huckster posing as Elijah (you can read about that here).

Beyond Elijah, two ads fully arrest Bloom’s involuntary attention in “Lestrygonians”: Kino’s 11/- trousers and Hely’s sandwichmen. Let’s analyze each of these and see if they appeal to a modern ad-master like Bloom.

Kino’s 11/- Trousers

Let’s look at the ad that topped Bloom’s “nice” list in “Ithaca”:

“His eyes sought answer from the river and saw a rowboat rock at anchor on the treacly swells lazily its plastered board.

Kino’s

11/—

Trousers

Good idea that. Wonder if he pays rent to the corporation. How can you own water really? It’s always flowing in a stream, never the same, which in the stream of life we trace. Because life is a stream.”

The Kino’s rowboat is successful first and foremost because of its motion. It rocks up and down, back and forth in the flowing stream of life, the River Liffey. The bobbing motion is enough to grab the attention of anyone glancing over the side of the O’Connell bridge. It more effectively navigates the stream of life as it rolls with the waves and current rather than being dragged along involuntarily like the crumpled Elijah throwaway. In the book The Economy of Ulysses, Mark Osteen writes:

“... because it is displayed on water, the Kino’s ad is not stationary; its power to arrest attention, to make the viewer pause, paradoxically depends upon its wavelike motion. Up and down, back and forth – the ad is anchored yet always moving, its magnetism resulting from its imitation of the ‘stream of life’ that constantly repeats yet always changes.”

A rowboat in the Liffey, 28 January 2023

Furthermore, Bloom’s momentary pondering of the Kino’s ad deepens and expands the water motif already present in Ulysses. We see the power and wildness of the stream of consciousness that Bloom has tapped into, a stream that has no master. It’s all rolled up in the cozy absurdity that we were led to these insights by a trouser ad. Delighted by the unexpected placement of the Kino’s ad, Bloom thinks of the possibilities of novel ad space:

“All kinds of places are good for ads. That quack doctor for the clap used to be stuck up in all the greenhouses. Never see it now. Strictly confidential. Dr Hy Franks. Didn’t cost him a red like Maginni the dancing master self advertisement. Got fellows to stick them up or stick them up himself for that matter on the q. t. running in to loosen a button. Flybynight. Just the place too. POST NO BILLS. POST 110 PILLS. Some chap with a dose burning him.”

The charlatan Dr. Hy Franks advertises for treatment of gonorrhea (aka the clap) in urinals. He certainly has a captive audience. Though Bloom is amused by this unorthodox ad campaign, its memory shakes loose fear in his mind that Boylan might transmit just such an infection to Molly:

“If he...?

O!

Eh?

No... No.

No, no. I don’t believe it. He wouldn’t surely?

No, no.”

Once Bloom shakes free of this momentary panic, Dr. Franks has been pushed from his mind, replaced by refreshingly unsexy thoughts of parallax and Dunsink time. Dr. Franks’ ad has only gone dormant in Bloom’s subconscious, though, as it resurfaces later in “Circe” merged with Kino’s ad:

“THE FLYBILL: K. 11. Post No Bills. Strictly confidential. Dr Hy Franks.”

Transformed into an emblem of Bloom’s sexual anxieties, Dr. Franks reflects Bloom’s sexual misdeeds more than you might think. Hy Franks and Henry Flower share initials, afterall, and “Hy” is a nickname for “Henry.” The once delightful Kino’s 11/- Trousers has been condensed to K.11 and, like Dr. Hy Franks, has absorbed some of Bloom’s anxiety.

K.11 actually precedes the Kino’s rowboat by two episodes in Ulysses. Towards the end of “Hades”, as Bloom tries to figure out where M’Intosh has disappeared to, a half-remembered fragment of a song lyric pops up in his mind: Kay ee double ell. Kell. With a little massaging this can become K.11. The “double ell” looks like the number 11. What about the “ee”? This is where it gets tricky. Scholar Robert Adams points out that K.11 is a reference to the kabbalah and that this combination of letter and number symbolizes resurrection. Once kabbalah is in the mix, we can graft Hebrew spelling rules onto this phrase and suppress the vowel. Thus, we get K.11, a symbol of resurrection, renewal, or perhaps something darker tucked into a trouser ad.

K.11 goes quiet for a while before resurfacing in “Circe” as an answer to a question:

“CHRIS CALLINAN: What is the parallax of the subsolar ecliptic of Aldebaran?

BLOOM: Pleased to hear from you, Chris. K. 11.”

K.11 is mixed in with a couple important details here, but just as when it’s associated with Dr. Hy Franks, it points to Bloom’s sexual anxiety. In this scene, Chris Callinan is asking Bloom about the parallax of the star Aldebaran, just the sort of question to delight Bloom’s inner science geek. Luckily, Bloom has the answer in his back pocket – it’s K.11, of course. But wait, who the heck is Chris Callinan? We must turn to “Wandering Rocks” for the answer. Callinan appears in a story courtesy of Lenehan, who, as always, is just the worst. Lenehan is regaling M’Coy with the time he shared a car home from a fancy dinner in Glencree with the Blooms and Chris Callinan. Bloom and Callinan were on one side, and Bloom was eagerly pointing out various stars and constellations to his captive audience. Meanwhile, Lenehan was seated next to Molly, who had had a little too much to drink, and in Lenehan’s own words:

“...by God, I was lost, so to speak, in the milky way.”

What emerges in Bloom’s subconscious in “Circe” is the memory of feeling like a fool for pointing out stars like an eager grade school student while another man is groping his wife across the carriage. Both Lenehan and Callinan are listed on Bloom’s list of men he suspects Molly of “having relations” with, however we are defining that. It’s not clear to me whether or not Bloom is slutshaming Molly or just painfully aware that other men have made moves on her, sometimes right in front of him. It is common enough for a woman to be blamed for an assault perpetrated against her, but it’s not clear to me that Bloom is blaming his wife for the Glencree incident. He may just feel humiliated due to Lenehan’s brazen disrespect.

Turning back to Kino’s trousers, Kino isn’t the only 11 shilling trouser man in town. We learn in “Hades” Bloom’s tailor is one Mr. George Mesias, but later in “Sirens”, we learn that Mesias is also seeing other people, so to speak:

“...a young gentleman, stylishly dressed in an indigoblue serge suit made by George Robert Mesias, tailor and cutter, of number five Eden quay, and wearing a straw hat very dressy, bought of John Plasto of number one Great Brunswick street, hatter.”

Mesias also made the suit that Boylan is wearing to meet Molly that very day. In “Circe”, we learn the price of a pair of Mesias’ trousers:

“MESIAS: To alteration one pair trousers eleven shillings.”

“Mesias” can also mean “Messiah”, but it would seem there is no resurrection or renewal for Bloom in Mesias’ 11/- trousers, either. As Osteen points out, Mesias has altered more than just Bloom’s trousers. He has indirectly altered Bloom’s marriage. Bloom must take up the mantle of savior, which he does for Stephen by settling his bill in Bella Cohen’s – 11 shillings in total. Osteen writes:

“Eleven shillings will buy you new trousers, or alter your old ones; it might also save you from Circe.”

Hely’s

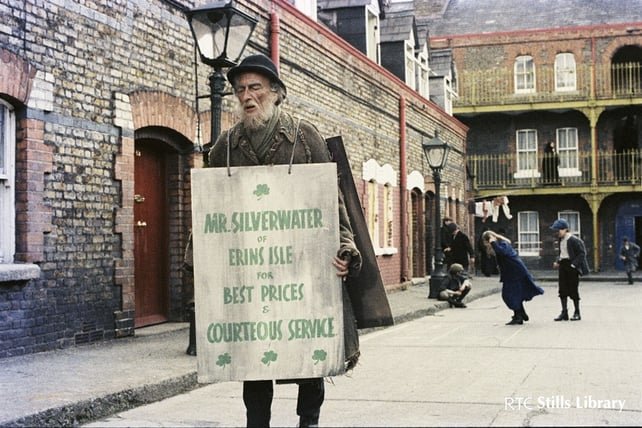

“A procession of whitesmocked sandwichmen marched slowly towards him along the gutter, scarlet sashes across their boards. Bargains. Like that priest they are this morning: we have sinned: we have suffered. He read the scarlet letters on their five tall white hats: H. E. L. Y. S. Wisdom Hely’s. Y lagging behind drew a chunk of bread from under his foreboard, crammed it into his mouth and munched as he walked. Our staple food. Three bob a day, walking along the gutters, street after street.”

A living, mobile ad joins the circulation of Westmoreland St. ahead of Bloom. Though the sandwichmen are advertising for the stationer Wisdom Hely, Bloom’s first thoughts are of the divine. They rouse the memory of the sodality clad in red scapulars that Bloom had encountered in All Hallows Church back in “Lotus Eaters”:

“Women knelt in the benches with crimson halters round their necks, heads bowed. A batch knelt at the altarrails. The priest went along by them, murmuring, holding the thing in his hands. He stopped at each, took out a communion, shook a drop or two (are they in water?) off it and put it neatly into her mouth.”

Like the worshippers receiving their daily bread in the form of the Eucharist, the Hely’s Y has taken matters into his own hands, munching on a cheeky bit of bread while on the job. While some ads, like Plumtree’s Potted Meat, make quasi-religious promises, the Hely’s sandwichmen appear as a silly echo of the religious rite Bloom encountered earlier in the day. Additionally, Bloom is on his way to perform the “rite of Melchisedek” as he describes it in “Ithaca” - a simple collation of bread, gorgonzola and wine. According to Gifford and Seidman’s Ulysses Annotated, Bloom’s rite of Melchisedek in “Ithaca” refers to a simple, “unsubstantial” lunch taken by Jewish priests. The Hely’s Y is practicing this rite, as a hastily consumed bit of bread isn’t terribly nourishing but at least it’s something. Though, I suppose, there is something oddly cannibalistic about a “sandwichman” devouring bread.

Beyond a tenuous connection to the Old Testament through Melchizedek, the Hely’s sandwichmen mimic Bloom’s forebears in other ways. Unlike the Kino’s billboard and its landbound cousins, the Hely’s sandwichmen are homeless wanderers, trudging through the streets of Dublin without a true destination. Their purpose is not to arrive, but simply to circulate. They call to mind the wandering of the Hebrews in Exodus. The Hebrews were searching for their Promised Land, so what about the sandwichmen? We can assume they will end wherever they started, but in “Wandering Rocks”, they are described as “plodding towards their goal,” giving their ultimate destination an air of uncertainty. There is a futility to their wandering, more akin to the mythological Wandering Jew. Both of these metaphors connect them to Bloom, a Jewish man wandering through Dublin concerned about his home. Of course, Bloom is also our Irish Odysseus, and the Hely’s sandwichmen wander in search of a distant destination, too. They also appear in the narrative just before Bloom encounters Denis Breen and Cashel Boyle O’Connor Fitzmaurice Tisdall Farrell, implying that some madness or mania drives the sandwichmen as well. For three bob a day, they must be desperate to accept that pittance. Like Bloom, they are also driven by hunger. We mustn’t begrudge Y his bit of bread.

Bloom is no stranger to economic desperation. He has yet to don a sandwich board, but like the sandwichmen, he once relied on Wisdom Hely for employment. Bloom worked in Hely’s for six years, but left in 1894:

“Got the job in Wisdom Hely’s year we married. Six years. Ten years ago: ninetyfour he died yes that’s right the big fire at Arnott’s.”

“Ninetyfour he died” refers to the death of Bloom’s infant son, Rudy. Bloom had trouble holding down a job the year of his son’s death, losing jobs in Hely’s, the cattle market, and at Thom’s that year alone. Molly began selling used clothes out of the Bloom’s house at that time to make ends meet. It demonstrates just how devastating the loss of Rudy was on the Bloom household. It’s no wonder that his absence continues to disrupt the Blooms’ marriage so profoundly ten years on.

In this passage in “Lestrygonians”, Bloom doesn’t linger long on these sad memories, but slips right back into his various advertising schemes. Bloom recalls pitching various clever ad schemes to Hely, but it seems his former employer, at least in Bloom’s opinion, was a bit too conservative to appreciate them. With regard to the sandwichmen, Bloom is very quick to scoff that this tactic “doesn’t bring in any business.” They are mobile and eyecatching, like the Kino’s rowboat, but they lack the juice to generate any authentic excitement or interest. Of course, the Hely’s sandwichmen are a reminder of a former employer that Bloom may have ended with on bad terms and of the year of his son’s death. It’s quickly apparent that part of Bloom’s dislike for the sandwichmen is that Hely refused to hear him. For instance:

“I suggested to him about a transparent showcart with two smart girls sitting inside writing letters, copybooks, envelopes, blottingpaper. I bet that would have caught on. Smart girls writing something catch the eye at once. Everyone dying to know what she’s writing. Get twenty of them round you if you stare at nothing. Have a finger in the pie. Women too. Curiosity. Pillar of salt. Wouldn’t have it of course because he didn’t think of it himself first.”

This idea clearly appeals to Bloom’s own particular fantasy of a smart writing girl. He’s definitely leaning into the Bridgewater school of advertising here, using sex appeal to sell stationery. “Everyone dying to know what she’s writing” - Bloom’s showcart appeals to natural human curiosity, allowing potential customers to construct their own story around the writing girls, personalizing a scene that’s fairly generic. Finally, Bloom incorporates mobility and circulation, like the Kino’s rowboat. You can almost feel the wink as Osteen points out the too-cute pun built into Bloom’s showcart: “... though it promotes stationery, it would not be stationary.”

On the other hand, showcarts weren’t exactly a new idea in 1904. They had been employed by Victorian advertisers and might come across as gimmicky at best or simply end up an extravagant expense for the advertiser with only modest returns. Alonso describes Bloom’s showcart as more of a “license to observe than a serious attempt to sell.” As readers, we can infer that Bloom’s interest in Martha didn’t arise out of nowhere. Perhaps Hely was also aware of Bloom’s tastes and clocked that this supposedly revolutionary ad campaign was Bloom’s attempt to make his fantasy a reality.

Bloom’s objections to other Hely ads reveals that his old boss did have more misses than hits, at least in Bloom’s surely biased memory. There’s the infamous Plumtree’s ad run beneath the obituaries, which, while it carries a nice, lestrygonian cannibalism motif for us literary types, is rather ghoulish when you think about it even a little. Hely’s ads for envelopes and erasers hearken back to those overly verbose Victorian ads we talked about earlier:

“You can’t lick ’em. What? Our envelopes. Hello, Jones, where are you going? Can’t stop, Robinson, I am hastening to purchase the only reliable inkeraser Kansell, sold by Hely’s Ltd, 85 Dame street.”

What is Szombathely without Hely’s? Incomplete.

I’d like to turn back to those Hely’s sandwichmen once more and explore one of the most unexpected allusions that may be tucked into their subpar ad. Scholar Barry McCrea expounds in an article entitled “Secrets of Szombathely: The H.E.L.Y.'S Sandwichmen and Irish Citizenship”, that while the Hely’s sandwichmen symbolizes the nomadic ways of Bloom’s ancient ancestors, they also parallel the immigrant journey of his 19th century relatives, including his father.

Main Square of Szombathely, Hungary (Image Source)

Szombathely, Hungary is the ancestral home of the Virag family, migrants who trekked across Europe to make a home in Dublin, where Rudolf Virag changed his name to “Bloom” and raised a son called Leopold. Here’s where things get weird. McCrea shows that Hely’s is hidden in the Blooms’ hometown:

Szombat-HELY

It’s even better if you consider the word “Szombathely” as circular rather than linear, allowing the inital “S” in “Szombathely” to become the final “S” in “Hely’s.” Think of how the first and final lines of Finnegans Wake merge to form one sentence, if that’s helpful. It gets weirder, though. Szombathely contains the letters M, L, and S, the first initials of Ulysses’ main characters. It also contains all the letters of Bethlehem. McCrea also shows that you can spell stately, yes, Bloom, Molly, Leo, Blazes and maze (for the Dedalus, the labyrinth builder), but that none of these are possible if you remove M, E, A, and T.

If anagrams aren’t your thing, McCrea calculates the alphanumeric value of the letter in Szombathely as 11, once again symbolizing renewal, just like the Kino’s ad. Don’t worry, he shows his work in the footnotes:

That S sandwichman that plods past Bloom on Westmoreland St. could easily stand for Stephen, a living symbol of the pair’s always-crossing-but-never-meeting paths in the middle part of Ulysses. McCrea takes it one step further though, pointing out the sandwich board actually bears an ‘S, marking the genitive case of “Hely”, which might lead us to the book of Genesis or to the quality of possession and paternity that spiritually link the metaphorical father and son, Bloom and Stephen. To get Wake-y once more, the Joycean coinage “perihelygangs” appears in Finnegans Wake, which McCrea says is a shortened version of “peregrinations of Hely.”

As far as I can tell, these deductions are McCrea’s and do not come from Joyce’s notes or comments. There’s a chance this is all simply coincidental, but it is certainly fun to think about. McCrea says the term “perihelygangs” is a reference to The Book of Invasions, a mythological account of Ireland’s history. As the title would suggest, The Book of Invasions tells how Ireland has been settled and resettled by wave after wave of mythical invaders, culminating in the Milesian conquest that we’ve discussed previously on the blog. In recorded history, this cycle has continued with the Vikings, the Normans and the Plantation of Ulster. Immigrants like the Blooms are not invaders of Ireland, instead they are migrants looking for a home who ultimately became members of the Dublin community. Immigrants arriving in Ireland from around the world are part of a long history, both mythological and factual, that has added to the rich tapestry of the Irish people.

Further Reading:

Adams, R.M. (1974). Hades. In C. Hart & D. Hayman (eds.), James Joyce’s Ulysses: Critical essays (91-114). Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/wu2y7mg

Alonso, S. (2018). Advertising in “Ulysses.” European Joyce Studies, 26, 107–129. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44871444

Del Río Molina, B. (2006). From Iconophagy to Anthropophagy: Cannibalising Images in Ulysses. Papers on Joyce, 12, 25-43. Retrieved from http://www.siff.us.es/iberjoyce/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/6-PoJ12-Benigno.pdf

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/vy6j4tk

Gunn, D. P. (1996). Beware of Imitations: Advertisement as Reflexive Commentary in Ulysses. Twentieth Century Literature, 42(4), 481–493. https://doi.org/10.2307/441878

Hastings, P. (2013). Leopold Bloom’s “Curriculum Vitae.” James Joyce Quarterly, 50(3), 824–829. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24598582

McCrea, B. (2004). Secrets of Szombathely: The H.E.L.Y.’S Sandwichmen and Irish Citizenship. James Joyce Quarterly, 41(3), 397–405. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25478067

Osteen, M. (1995). The economy of Ulysses: making both ends meet. New York: Syracuse University Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yycf2ar5