A Shakespearean Ghoststory Part 3: Gilbert, Richard, and Edmund

Near the end of “Scylla and Charybdis,” Ulysses’ ninth episode, Stephen arrives now at the rousing conclusion of his Shakespeare theory: not only did Shakespeare write his wife and son and himself into Hamlet, but he also wrote his brothers into several other plays! And much like with Ulysses, it’s never good news that you’ve been included in one Shakespeare’s plays. Stephen’s conjecture in the case of the Shakespeare brothers, Gilbert, Richard, and Edmund, is that Richard and Edmund did something unforgivable and therefore are immortalized as two of the worst Shakespearean villains (Richard III, and Edmund from King Lear, respectively). Gilbert gets off scot free, so he must have been nice to brother Will:

“[Gilbert] is nowhere: but an Edmund and a Richard are recorded in the works of sweet William.”

Stephen assumes Richard and Edmund both hooked up with Will’s wife Anne while their older genius brother was away in the big city being the greatest genius to ever write in the English language. Will had no choice but to exact his revenge on the page and on the stage:

“In his trinity of black Wills, the villain shakebags, Iago, Richard Crookback, Edmund in King Lear, two bear the wicked uncles’ names.”

Shakespeare had sisters in addition to his three brothers, though most of them didn’t make it out of childhood; his sisters Joan and Margaret both died before Will, the third child, was born. Gilbert followed Will, then another Joan, Anne (who died in childhood), then Richard, and finally Edmund, who was sixteen years younger than Will. Likewise, James Joyce was the oldest of four brothers, though he had many more sisters than Shakespeare.

As with our examinations of Shakespeare’s son and wife, it’s anybody’s guess what Will thought of them, positive or negative, because we have almost no records whatsoever. No diaries, no correspondence, etc. Unsurprisingly, there’s also very little surviving information on Will’s younger brothers. Stephen is really taking some big swings with his claims about Shakespeare’s family relationships, and he knows it. His ideas are mainly gleaned from little clues in Shakespeare’s work, like tea leaves to be read by this young, up-and-coming genius. Let’s examine what we do know about each of the Shakespeare brothers and try to draw some conclusions for ourselves.

Gilbert

Gilbert was Will’s oldest younger brother, two years his junior. With all of the Shakespeare brothers, there are very few verifiable facts about their lives, so we have to work with what we’ve got. For instance, we can deduce that Gilbert was literate because of a single surviving signature on a legal document. Presumably, he attended the same school as his brother Will, but we don’t know. He is believed to have worked as a haberdasher, but there is no record of him having a shop in Stratford or London, as well as no record in the parish registry or membership in the local organization for haberdashers. This introduces the dominant ambiguity when dealing with any member of the Shakespeare family, including the Bard himself. None of this means Gilbert wasn’t a haberdasher; it also doesn’t mean he was. He may have been some kind of clandestine, unregistered haberdasher. We simply don’t know for sure.

Germaine Greer notes in her biography of Anne Hathaway, Shakespeare’s Wife, that Gilbert was a lifelong bachelor. When Will worked so hard to acquire a coat of arms for the family in 1596, Gilbert was in his thirties and still single. When their mother Mary died in 1608, Gilbert was a swingin’ 41-year-old single. It would be unusual for a man to reach his thirties in those days and still be a bachelor, so Greer draws some conclusions based on these unusual circumstances:

“Gilbert would have attained his majority in October 1587; unless his father really and truly had no money whatsoever Gilbert must have been a worthwhile marriage prospect for someone.”

Greer explains that Mary Shakespeare came from a good family and had many social connections to make a match for Gilbert. John Shakespeare, on the other hand, was not without financial and legal troubles throughout his life, as we’ve discussed in other blog posts. Greer speculates that John may have had such a strong reputation as “a jumped-up wastrel who had impoverished his wife and children” that the prospect of marrying Gilbert was radioactive as a result. Having a famous brother might have helped, but it seems brother Will threw his money behind that coat of arms, a dream of their father’s, rather than use his money and influence to find Gilbert a bride. Of course, the coat of arms confers the status of gentleman onto John Shakespeare and his heirs, including Gilbert, but that seemingly did not move the hearts of the eligible young women of Stratford in the 1590’s.

Gilbert died in 1612 and left no will and no heirs, so we get no further insight there, either. We get one additional glimpse into Gilbert’s life in a Stratford court record from 1609, in which Gilbert was accused of being part of a group of men who committed a violent, retributive assault against a local woman. There is no record of conviction or other court proceedings. There is a possibility that Gilbert was merely a violent goon part of the time and a half-assed, unlicensed haberdasher the other part. Maybe Gilbert just sucked, and that’s why things didn’t go well for him, coat of arms be damned.

Stephen takes a much rosier view of ol’ Gilbert. In fact, he’s the only Shakespeare brother that Stephen says anything positive about at all. Why exactly does Stephen think Gilbert was a chill dude? Well, because he was spared the ignominy of being named in a Shakespeare play, of course! Stephen shares the following anecdote:

“He had three brothers, Gilbert, Edmund, Richard. Gilbert in his old age told some cavaliers he got a pass for nowt from Maister Gatherer one time mass he did and he seen his brud Maister Wull the playwriter up in Lunnon in a wrastling play wud a man on’s back. The playhouse sausage filled Gilbert’s soul. He is nowhere: but an Edmund and a Richard are recorded in the works of sweet William.”

Stephen recounts this tale about Gilbert in a mock-Warwickshire dialect. Gilbert reminisced late in life that he had once journeyed up to “Lunnon” to see his brother act, so the story goes. We can work out Will was playing Orlando in As You Like It, which does include a “wrastling” scene (though as annotators Gifford and Seidman admonish, “Needless to say, As You Like It is not a play about wrestling.”)

This tall tale came to Stephen/Joyce via scholar Sidney Lee’s 1898 book A Life of Shakespeare. Lee’s source for Gilbert’s story is author William Oldys, who would have been around 16 when Gilbert died in 1612. That is to say, this isn’t exactly a primary source. Lee emphasized that Gilbert’s memory was going at the time he recounted the story, as Oldys claimed Gilbert lived to “patriarchal age.” For clarification, Biblical patriarchs like Noah or Methuselah both lived well into their 900’s. If baptismal and death records from Stratford are to be believed, Gilbert checked out in his mid-40’s. Additionally, in Oldys’ version, Will only played the servant Adam in As You Like It, so no wrastlin’. It looks like Stephen beefed up Will’s on-stage role to give his tall-tale that little extra oomph in the retelling. Scholar Robert Adams notes that the passage in Gilbert’s Warwickshire dialect was added to Ulysses late in the game, describing it as a “Joycean afterthought,” which would “suggest an effort to impress as well as to divert.” I’d have to agree with Adams on this one.

Richard

Richard Shakespeare was born ten years after Will, and what we know of Gilbert is positively exhaustive compared to Richard. Like Gilbert, Richard was a lifelong bachelor, which adds to Greer’s supposition that there was something so rotten in the house of Shakespeare that two should-be-eligible bachelor sons never made a match. Richard was 23 at the time he was conferred the status of “gentleman” in 1596, but Greer writes that he was “apparently uneducated and good-for-little,” indicated by the fact that, like Gilbert, his brother made no effort to find him a bride. Richard died almost a year to the day after Gilbert and also left no will.

Like Gilbert, Richard also appeared in the Stratford court records. In 1608, he was presented to the Vicar’s Court with two other men and fined 12p. Greer editorializes, “what they had all been up to is anybody’s guess,” as, you guessed it, there is no record of why he was fined. 12p was apparently an abnormally high fine for the early 17th century. Greer compares this to the typical fine of 1-2p for the heinous crime of plowing with oxen on the sabbath in the same time period. Richard, like Gilbert, was clearly up to no good, adding to my growing suspicion that these Shakespeare boys were a bunch of ne’er-do-wells. Maybe Will was lucky to get out when he did. It might also explain why he was willing to live and work so far from his own wife and kids. Maybe it wasn’t because Anne was an evil shrew, but because his brothers were a bunch of deadbeats. If his family had as bad a reputation as Greer suggests, he was likely all too happy to leave them in the dust.

The name Richard appears in Shakespeare’s plays, notably in the history play Richard III, as one of Shakespeare’s most loathsome villains. To Stephen, this is damning evidence that Richard Shakespeare shacked up with Anne Hathaway-Shakespeare while Will was nobly away in London being an artistic genius. In any case, Stephen has already anticipated your rebuttals to his claim:

“—You will say those names were already in the chronicles from which he took the stuff of his plays. Why did he take them rather than others? Richard, a whoreson crookback, misbegotten, makes love to a widowed Ann (what’s in a name?), woos and wins her, a whoreson merry widow. Richard the conqueror, third brother, came after William the conquered. The other four acts of that play hang limply from that first. Of all his kings Richard is the only king unshielded by Shakespeare’s reverence, the angel of the world.”

Richard III (1955)

Yes, Richard III marries a woman named Anne Neville, who was a real woman who really wed the real Richard III. To find Stephen convincing here, you would also have to ignore the fact that Richard III lost a civil war to Henry VII, the first of the Tudor line and ancestor of Queen Elizabeth I, Shakespeare’s patron. I’ve already discussed the propaganda found in Shakespeare’s plays during the Elizabethan era. There was political value in portraying the queen’s historical adversaries as hyperbolically evil. Stephen himself has astutely argued this point, so his obtuse reasoning here is contradicting his own previously well-delivered arguments. Stephen’s whole theory is beginning to fray and unravel. We should consider that Stephen is operating on nothing but three drams of whiskey and a prayer. It’s actually impressive he made it this far at all.

Edmund

Edmund was Will’s youngest brother, 16 years the playwright’s junior, and that’s right, we know almost nothing about him. Given the scant facts we have about his father and two-thirds of his older brothers, Edmund was likely dealt a cruel hand in life. When Will secured the family coat of arms in 1596, technically making Edmund a gentleman, Greer described him as hopelessly “devoid of prospects.” Edmund left Stratford for London at some point to follow in his oldest brother’s footsteps as a “player.” Sadly, he died at the age of 27, just six months after his infant son. Like his brothers, he left no will. Greer notes that virtually no Shakespeare family member left a will except, well, Will. On the other hand, many of the Hathaways had wills, leading Greer to suspect that the infamous second-best bed will was written at Anne’s insistence rather than Will’s.

Of course, we don’t know for sure if Edmund and Will met up in London, but it seems they must have. Some commentators write that they lived together, but that is mere speculation. The most compelling reason to believe Will was quite fond of his baby brother is the circumstances of Edmund’s funeral. Edmund was buried in St. Saviour’s Church (now Southwark Cathedral), his funeral accompanied by the knelling of the great bell of the church. That bell doesn’t knell for just anybody, as it cost 20 shillings to get it ringing in 1607. It’s speculated that Will paid for this distinct honor for his baby brother, gone too soon, as Edmund wasn’t likely to have left behind bell-knelling money. Greer contrasts this outpouring of commemoration for Edmund with the spare and simple funeral for the Shakespeare matriarch Mary at her passing the following year. So, if Will did indeed send Edmund off in style, he made no similar arrangements for his mother. The reasons for this are, of course, lost to history.

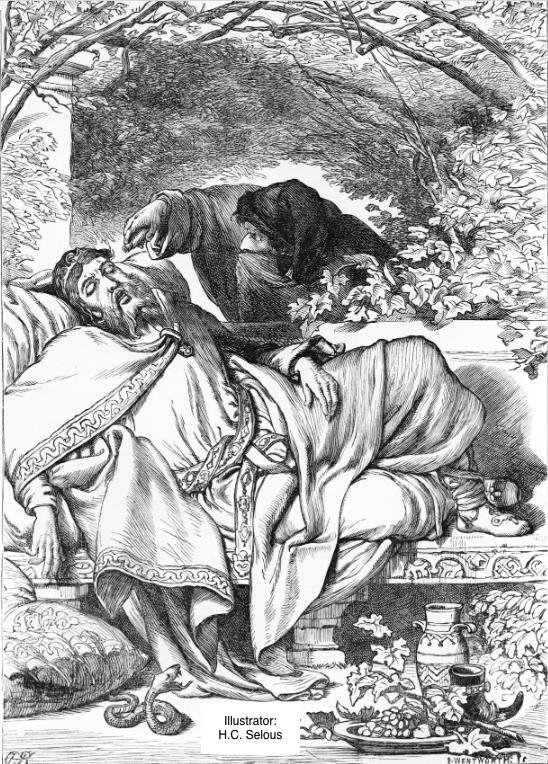

Stephen has no kind words for Edmund Shakespeare, based on the evidence that Will borrowed his brother’s name for the double-crossing bastard Edmund in King Lear:

“In his trinity of black Wills, the villain shakebags, Iago, Richard Crookback, Edmund in King Lear, two bear the wicked uncles’ names. Nay, that last play was written or being written while his brother Edmund lay dying in Southwark.”

As with Richard, Stephen questions why Shakespeare used the name Edmund in King Lear:

“Why is the underplot of King Lear in which Edmund figures lifted out of Sidney’s Arcadia and spatchcocked on to a Celtic legend older than history?”

This Edmund is not a historical figure like Richard. He’s correct that the Gloucester subplot in King Lear was borrowed from Arcadia, where the characters all had Greek names, so presumably using “Edmund” was a creative choice. Nonetheless, Stephen argues that Edmund likely committed the same heinous crime as Richard — knocking boots with their sister-in-law:

“Because the theme of the false or the usurping or the adulterous brother or all three in one is to Shakespeare, what the poor are not, always with him.”

Stephen’s evidence here is pretty thin. There are all kinds of reasons that Will might have used his brother’s name other than revenge. In my head canon, maybe it was an edgy in-joke between brothers who were best friends. I think my evidence for this is stronger than Stephen’s, given the circumstances of Edmund’s funeral, but like Stephen’s theory, my conclusion is still purely fanfiction. It feels like Stephen is starting from a conclusion (Shakespeare’s plays are autobiographical) and working backwards, biasing details that prove his forgone conclusion. No one in the library is convinced and neither should we be as readers. That’s all okay, though, because there are reasons rather than the dissemination of strict historical fact that Joyce would include these arguments in his novel.

Is Stephen projecting?

Previously, I’ve written about how when Stephen/Joyce is throwing around erroneous biographical details about Shakespeare, he’s actually talking about larger themes embedded in the novel. This is true of the passages about Gilbert, Richard and Edmund as well, and adds richness to the overarching theme of paternity found throughout Ulysses.

If you favor the Oedipal interpretation of Hamlet and Shakespeare’s work at large (which I discussed here), expanding that interpretation to include Shakespeare’s brothers deepens its complexity. Scholar Jean Kimball points out that Stephen incorporates all of Shakespeare’s family into his argument even though it’s not strictly necessary if he’s only concerned with paternity. It becomes necessary to include the brothers, however, if Stephen’s argument has some basis in the psychoanalytic framework of the “new Viennese school,” which I previously explored here. Kimball’s argument is based on psychoanalyst Otto Rank’s interpretation of Hamlet based on the Freudian concept of the Oedipal Complex and incest. For Rank, Hamlet portrays the full spectrum of incestuous possibilities, including among hostile brothers. In Hamlet, this is fulfilled by Claudius’ murder of Hamlet Sr., and fits Stephen’s belief that Shakespeare’s work is riddled with examples of “the false or the usurping or the adulterous brother.” If Shakespeare related most to the Ghost in Hamlet, as Stephen argues, his rage is directed at the figure of Claudius (Richard-Edmund) hooking up with Gertrude (Anne) once King Hamlet/Ghost (Will) was out of the picture.

The treacherous brother motif did not originate in Hamlet, though. I want to give Best his flowers, as he correctly points out the prevalence of dastardly brothers in much older mythology:

“—That’s very interesting because that brother motive, don’t you know, we find also in the old Irish myths. Just what you say. The three brothers Shakespeare. In Grimm too, don’t you know, the fairytales. The third brother that always marries the sleeping beauty and wins the best prize.”

Scholar William Sayers argues that this is Best’s strongest contribution in the entirety of “Scylla and Charybdis.” Irish mythology is Best’s forte, afterall. Sayers gives as examples of treacherous brothers from Irish myth the Milesian brothers Éber Donn and Éber Finn, whose rivalry was their downfall, and also Niall of the Nine Hostages and his struggles against his half-brothers to become High King of Ireland.

Best, in real life, was the second of three brothers. Stephen thinks silently in response, “Best of Best brothers. Good, better, best.” Does he suspect that Best had a contentious relationship with his alpha younger brother? These details are lost to history. In any case, Best’s commentary on this long tradition of brotherly conflict in literature leads us to the disappearance of Stephen’s own brother, Maurice.

Stanislaus Joyce (source)

You won’t find any mention of Maurice in Ulysses or A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. You’ll have to dig into Joyce's unfinished novel Stephen Hero, an early prototype of Portrait, to find him. Maurice is based on Joyce’s younger brother Stanislaus, with whom Joyce maintained a close friendship throughout his life. Joyce thought it important for Stephen to be totally alone in the world, so that the kindness and friendship shown by Leopold Bloom would be more potent on the page. This was quite different from Joyce at a similar point in his life, as he not only had Stanislaus but also a romantic relationship with Nora. In any case, Stephen needed to be alone and alienated, so Maurice wound up on the cutting room floor. Joyce, never one to ignore a juicy morsel of obscure, inscrutable errata, gives this phantom brother a shout-out in “Scylla and Charybdis”:

“Where is your brother? Apothecaries’ hall. My whetstone. Him, then Cranly, Mulligan: now these.”

Stephen calls out to the memory of his brother, his creative “whetstone” who was succeeded by Cranly and then Mulligan. Stephen answers his own rhetorical question (Where is your brother?) with a concrete answer (Apothecaries’ hall). In early 1904, Stanislaus was working as a clerk in Apothecaries’ Hall in Dublin. Kimball says that Stephen’s silent question here echoes God’s question to Cain in Genesis, adding to the motif of the false, usurping brother. This is further reinforced by naming himself “voice of Esau,” a reference to one half of another set of Biblical brothers with a contentious relationship.

In the end, I think Stephen’s focus on bad brothers could ultimately be a projection of his own guilt, especially when combined with the theme of banishment he finds in Shakespeare’s work:

“The note of banishment, banishment from the heart, banishment from home, sounds uninterruptedly from The Two Gentlemen of Verona onward till Prospero breaks his staff, buries it certain fathoms in the earth and drowns his book.”

Stephen is a brother, after all. Even if Maurice is no more, there are still Dilly, Katey, Maggy, and Boody to think of. Stephen reflects periodically on their poverty, but takes no action. Dilly, who we’ll meet in the next episode, “Wandering Rocks”, begs their father Simon for money, which he’ll drink away with the lads rather than bring home. We already know Stephen is falling into the same well-trod pattern — wasting his salary on those washed-up newsmen rather than his starving sisters. Furthermore, he knows he is going to leave Dublin, already having been driven out of his own “Elsinore” by the usurper Mulligan. The guilt over leaving his sisters behind eats at Stephen, as he is failing in his role as a big brother to protect them. He is the false, failed brother. All that is left to him is self-imposed banishment.

Further Reading:

Adams, R. M. (1962). Surface and symbol: The consistency of James Joyce’s Ulysses. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ellmann, R. (1972). Ulysses on the Liffey. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.65767/2015.65767.Ulysses-On-The-Liffey_djvu.txt

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/vy6j4tk

Greer, G. (2008). Shakespeare’s Wife. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Kimball, J. (1976). James Joyce and Otto Rank: The Incest Motif in “Ulysses.” James Joyce Quarterly, 13(3), 366–382. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25487278

Peterson, R. F. (1990). Did Joyce Write “Hamlet?” James Joyce Quarterly, 27(2), 365–372. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25485041

Sayers, W. (2006). Best the Mythographer, Dinneen the Lexicographer: Muted Nationalism in “Scylla and Charybdis.” Papers on Joyce 12 (2006): 7-24. Retrieved from http://www.siff.us.es/iberjoyce/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/5-PoJ12-Sayers.pdf

Schutte, W. (1957). Joyce and Shakespeare; a study in the meaning of Ulysses. New Haven: Yale University Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/joyceshakespeare00schu

Simpson, J. (2025). Richard Best. James Joyce Online Notes. Retrieved from https://www.jjon.org/jioyce-s-people/richard-best