Who Was the Real Reuben J. Dodd?

“ I never liked Jimmy Joyce. He used to drink the altar wine.” - Reuben J. Dodd, Jr.

This post is a part of an occasional series on the real people behind the characters in Ulysses.

To listen to a discussion of this topic, check out the podcast episode here.

The Dublin of Ulysses is a mix of fictional and real-world events and people, sometimes rendered in precise detail (at least when it suits the author). Such real-world anecdotes often heavily influence the events of Ulysses, and therefore we must take them into consideration in a close reading of the novel. Best of all, Joyce wove some of these anecdotes into his novel for the purpose of petty score-settling against his least favorite Dubliners. With this in mind, let us consider the case of a Dublin solicitor by the name of Reuben J. Dodd.

“…the corner of Elvery’s Elephant house…” (image source)

“…the hugecloaked Liberator’s form.” (image source)

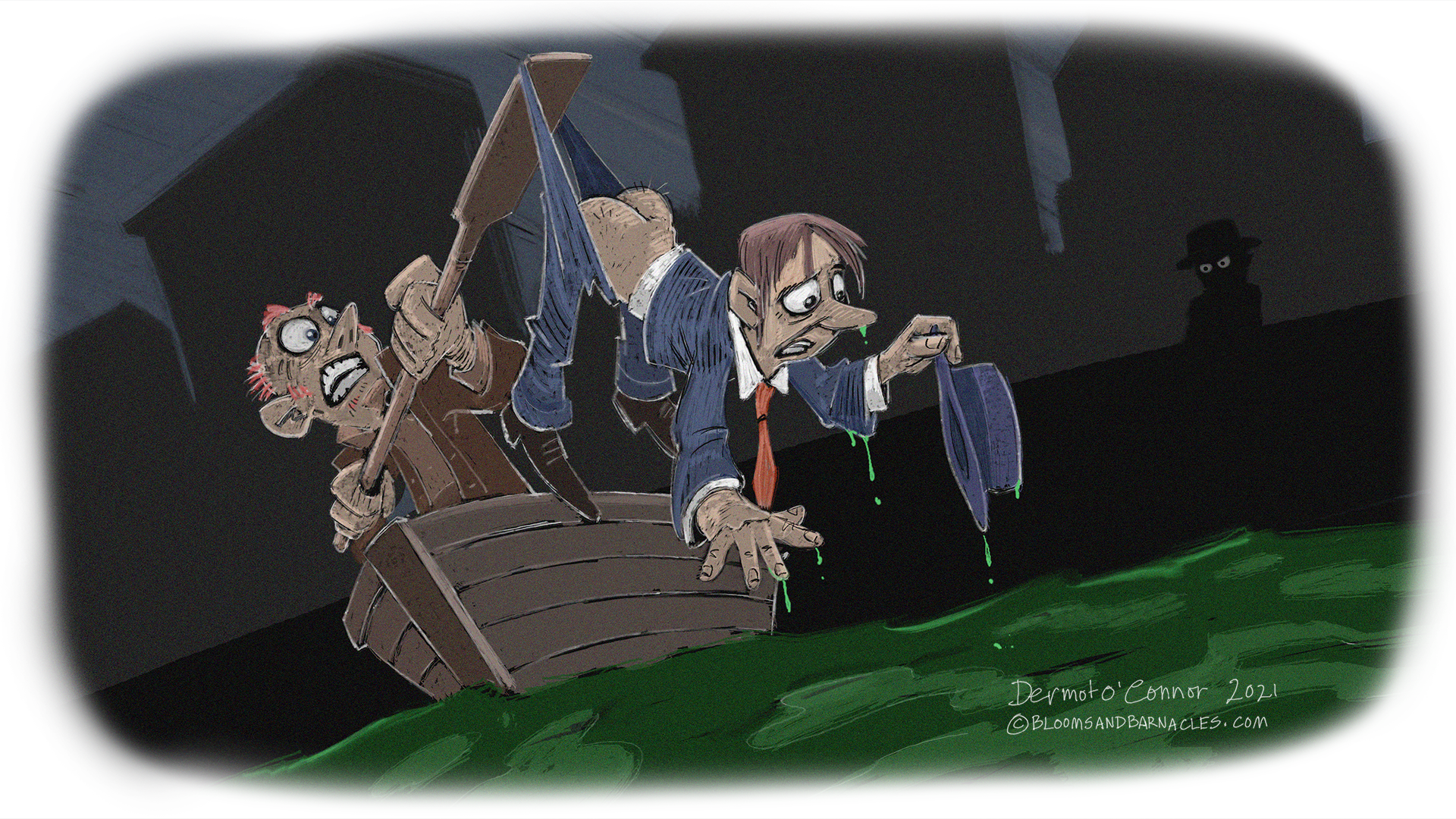

In “Hades”, Ulysses’ sixth episode, Paddy Dignam’s funeral cortège passes Reuben J. Dodd on the way to Glasnevin Cemetery, somewhere between the Daniel O’Connell statue and Elvery’s on Sackville St. (now O’Connell St.). Martin Cunningham spots him first, quipping to Jack Power, “Tribe of Reuben.” The men in the carriage clearly hold him in contempt, with Simon Dedalus remarking, “The devil break the hasp of your back!” Leopold Bloom tries to get in on the act and begins telling the story of how Reuben J. Dodd, Jr. (his son) jumped into the River Liffey, possibly to drown himself, and had to be fished out by a passing boatman. Dodd the Elder paid the hero boatman a measly florin for the trouble of saving his son’s life. Cunningham “thwarts [Bloom’s] speech rudely” and tells the story to much greater acclaim. Dedalus cries out “Drown Barabbas!” at Bloom’s description, and Cunningham describes Dodd the Younger as a “young chiseller.” Dedalus scoffs that the florin was “one and eightpence too much” for the life of Dodd the Younger.

As we continue on in the novel, we can also glean that Dodd is a moneylender (a “gombeen man” as he is called in “Wandering Rocks”), and that the men in the funeral carriage have felt the burden of his usury. Cunningham adds, “Well, nearly all of us,” while making eye contact with Bloom, so the antisemitic connotation is subtle but clear - Dodd, of the tribe of Reuben, a “Barabbas” of Dublin - is a Jewish moneylender, fleecing the good, Christian men of the Hibernian Metropolis, and thus only Bloom has eluded Dodd’s snares. Bloom, for his part, seems unrattled by the remark, plowing forward with his story about the circumstances of Dodd the Younger’s plunge into the Liffey. Perhaps Dodd really is a scoundrel, and Bloom doesn’t mind the trash talk. However, toward the end of “Lestrygonians,” Bloom thinks to himself, “The devil on moneylenders. Gave Reuben J a great strawcalling. Now he’s really what they call a dirty jew.” It’s a bit jarring to say the least. Is Bloom caught up in the antisemitism of his cohorts after all? Though he is only nominally Jewish, Bloom takes pride in his heritage and is clearly willing to defend it in the face of the Citizen’s bigotry. So who is this Reuben J. Dodd fellow, anyway? And what would prompt Bloom to call a fellow member of the tribe a “dirty Jew”?

Reuben J. Dodd was indeed a real person who knew John Joyce, James’ father and the model for Simon Dedalus. Dodd worked as a solicitor and had leant money to John Joyce. During James’ boyhood, his father fell on hard times, causing him to withdraw his bright, young son from the prestigious Clongowes Wood College and sell property that the Joyce family had long held in Cork to cover the debts owed to Dodd, events dramatized in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. To John Joyce, this process was deeply humiliating, and he never forgave Dodd. As Robert Adams put it in his book Surface and Symbol, “Reuben J. Dodd was in bad odor with James Joyce because he had loaned money to John S. Joyce, and, curiously expected repayment.” Simon’s vitriol toward Dodd in Ulysses is likely a direct reproduction of John Joyce’s rage toward the real-life Dodd. James had a connection to the Dodd family as well - he and Dodd the Younger attended Belvedere College at the same time, where they hated one another.

The story of the younger Dodd’s plunge into the Liffey from “Hades” has some basis in real life, as well. Dodd the Younger did jump into the Liffey, though in 1911 rather than 1904. It was rumored to be a suicide attempt, though the story about the young woman and the Isle of Man recounted in Ulysses may or may not be true. Dodd, for his part, claimed in later years that he fell in while trying to retrieve his hat. The story, reprinted in Richard Ellmann’s biography of Joyce, was recounted fairly colorfully in the Irish Worker. That publication wrote that of Dodd’s motivation for jumping, “we care not” and focused instead on the fate of the dock worker who fished him out. The Irish Worker recounts that Dodd the Elder paid half-a-crown for his son’s life rather than a florin, a half shilling more than what he paid in Ulysses, but still a tiny amount, though the Irish Worker editorializes, “Mr. Dodd thinks his son is worth half-a-crown. We wouldn’t give that amount for a whole family of Dodds.” It would seem at least on this point, the Irish Worker and Simon Dedalus are in agreement. The Irish Worker’s quarrel with Dodd appears to be class-based rather than antisemitic - a story of a working class man suffering due to the follies of the bourgeoisie.

The grudge between the Dodds and the Joyces lasted well beyond James’ lifetime. Like many folks portrayed in Ulysses, Reuben J. Dodd, Jr. was not pleased with his cameo. Decades after the novel’s publication, Dodd contacted the Dublin Law Library to file a libel suit against the BBC for a broadcast of a radio adaptation of Ulysses. The team that took on his case included a young Ulick O’Connor. Dodd’s suit claimed that he had turned on the radio to hear race results and was confronted instead with a voice claiming he was worth only 4 pence. As an aside, this scenario sounds so unlikely in my opinion that I personally believe that Dodd had had an axe to grind against Ulysses for years, got wind of the BBC broadcasting a version, and took his chances. O’Connor recalled the case was seen as a bit of a joke among his colleagues, who mocked it as “O’Connor’s cod case.” In any case, the BBC held out for a good, long while in court, but eventually settled with Dodd for what O’Connor described as a “considerable sum in those days.” O’Connor went on to say, “Reuben was delighted at this substantial financial contribution to his later years.” Dodd also attempted to sue the publishers of Ulysses, but with less success. His lawsuit set publishers on edge, though, and in the 1984 edition of Ulysses, the name H.Thrift was changed to the fictional H. Shrift.

One complaint that did not arise in Dodd’s suit, however, was antisemitism. Dodd was incensed by the implication that his life was worth less than a florin, but not so much that his father was depicted as a man so eager to collect a debt that he would send hired goons to stalk Fr. Cowley, as described in “Wandering Rocks”. Armed with the knowledge of the real-life Dodds, we can deduce that the Dodds were not, in fact, Jewish at all. Readers might see clues to Dodd’s Jewishness in his given name Reuben, his occupation as a moneylender, and his comparison with Barabbas and Judas Iscariot by the other characters, and of course there’s Bloom’s description of him as a “dirty Jew.” However, there are plenty of Gentiles named Reuben (even in Catholic Ireland) as well as Gentile moneylenders. On top of this, if Reuben J. Dodd, Jr. was Jewish, he couldn’t have attended Jesuit-run Belvedere College.

Matthew Kane, aka Martin Cunningham

Antisemitic slurs aren’t solely reserved for Jews, either. A person who truly believes the stereotype of a money-grubbing, hook-nosed usurer often applies the term “Jew” more broadly to anyone they believe is behaving in this manner. Such slurs are still in use in our current era. Bloom’s cohorts are certainly guilty of this. In the Dubliners short story “Grace,” Martin Cunningham, Jack Power, and others describe the character Harford as an “Irish Jew,” meaning an Irish Catholic who behaves like the negative stereotype of a Jew:

“[Harford] had begun life as an obscure financier by lending small sums of money to workmen at usurious interest. Later on he had become the partner of a very fat short gentleman, Mr Goldberg, in the Liffey Loan Bank. Though he had never embraced more than the Jewish ethical code his fellow-Catholics, whenever they had smarted in person or by proxy under his exactions, spoke of him bitterly as an Irish Jew and an illiterate and saw divine disapproval of usury made manifest through the person of his idiot son.”

Some scholars believe that Harford was a prototype for Dodd. Note the tossed-off comment about his “idiot son”. Harford, as this extract demonstrates, is a Catholic beyond a shadow of a doubt. He is even in the audience at Fr. Purdon’s seminar at the end of “Grace,” where he is spotted at a distance by Cunningham’s crew. If Joyce has already depicted these same characters in another work using “Jew” as a slur for a usurious Gentile, why not in Ulysses as well?

With this in mind, we can realize that referring to a person as a “Jew” does not mean they are literally Jewish as the term “Jew” has been co-opted as a slur in itself. Even if a character calls Dodd a “dirty Jew” or “Reuben J. Antichrist, wandering Jew,” we cannot assume that character literally believes him to be Jewish but rather is speaking from a place of internalized antisemitism. In this antisemitic mindset, to be a Jew is to be a conniving miser, and a conniving miser of any religion is therefore a kind of Jew. Joyce depicts this prejudice in Ulysses to show the hypocrisy of this belief. Take for example Lenehan, who accuses Bloom in “Cyclops” of “defrauding orphans and widows” while Bloom is actively collecting money to support Paddy Dignam’s widow and children.

This brings us back to the story of Dodd the Younger’s rescue from the Liffey. The man who rescued Dodd was named Moses Goldin. His identity is obscured in Ulysses, but his name gives us a hint that he likely was Jewish. Patrick McCarthy, writing in James Joyce Quarterly, sees this as a trap set by Joyce - to make the reader believe that Jewish Dodd is saved by a heroic Gentile when likely the opposite is true.

You may be thinking at this point, all the people in Ulysses are fictional, including those who existed in the real world. Dodd could become Jewish in a fictional context, no matter what faith he practiced in the real world. However, unlike in many other works of fiction, these untold, real-world anecdotes often do hang over the events of Ulysses, and therefore we must take them into consideration in a close reading of Ulysses. As Ellmann put it:

“Joyce’s surface naturalism in Ulysses has many intricate supports, and one of the most interesting is the blurred margin. He introduces much material which he does not intend to explain, so that his book, like life, gives the impression of having many threads that one cannot follow.”

It’s enough to turn your brain to scrambled eggs.

Joyce’s trap, then, may be too subtle for readers to catch if they don’t know the story of Dodd’s plunge. While this justifies my blog’s existence, it also has the power to alter how we interpret the actions and interactions of characters in the narrative of Ulysses. Take for instance Bloom’s reference to Dodd as a “dirty Jew.” Without knowing the full irony of Dodd’s story, this comment comes across as perhaps self-loathing, brought on by hearing his friends defame another Jewish Dubliner. He mocks Dodd right along with the other men in the carriage. It marks Bloom as a Dubliner, possessed of the same petty grudges and prejudices as his cohorts. Robert Adams certainly saw it this way, writing in Surface and Symbol:

“Bloom’s Jewishness served, for Joyce, as a vehicle for his own self-pity;... his self-loathing. As a Hungarian, Bloom has hardly any fictional functions; as a Jew, he has almost too many. This is only one of several circumstances which, taken in conjunction, make him seem more like a verbal device than a proper literary character.”

While I agree with Adams that Joyce was definitely working out some personal demons on the page in Ulysses, I find his conclusion to be too reductive in this case. By knowing the full story about Dodd, we know that Bloom is really listening to his friends defame an unscrupulous Christian as a Jew, that they use Bloom’s cultural identity as an insult for anyone they don’t like. Since the text never describes Dodd as Gentile, we can’t assume that Bloom sees him this way. However, if we choose to incorporate this outside knowledge into our reading of Ulysses, Bloom’s slur takes on an air of resentment, a sarcastic comment from a man who is tired of hearing “Jew” as an epithet but who knows he can’t change this prejudice. He has decided to go along to get along, but doing so wears on him.

Incubism

Let’s also take another look at Martin Cunningham’s comment that, “We have all been there…. Well nearly all of us.” The men in the carriage, with the exception of Bloom, feel the stifling incubism of excessive debt. If Cunningham is aware of this, what are the implications of this remark? Whether or not Dodd is truly Jewish, Cunningham may suspect Dodd and Bloom of being in the same swim. Recall the detail of Harford partnering up with a Mr. Goldberg in “Grace.” Does Cunningham see Bloom as another Mr. Goldberg? The Eye of Sauron is now focused on Bloom, regardless of whether he’s actually defrauding orphans and widows or not. He’s guilty by the most tenuous of association, even in the eyes of his friends. Bloom then tells the story of Dodd’s son falling in the river, knowing their opinion of the Dodds, in order to shift suspicion away from himself, and indeed the other men take the bait. He goes along to get along, but it still takes its toll, resurfacing as the “dirty jew” comment.

The introduction of Dodd’s tale into the narrative allows for the drowning motif established in the early episodes to resurface here in “Hades.” Recall how in “Proteus”, Stephen Dedalus envisions his father Simon as a drowning man. Bloom’s cohorts are using Jews as a scapegoat for their metaphorical, financial drowning. It’s especially ironic that Cunningham is the one to tell the story of Dodd the Younger’s near-drowning as Cunningham’s real-life counterpart, Matthew Kane’s “death by water” is recalled in “Ithaca.”

1904 Florin

1899 Florin

Mark Osteen, in The Economy of Ulysses, sees significance in the exchange of a florin for a life. Recall that real-life Dodd paid half-a-crown for his son’s life, but in Ulysses it was reduced to a florin. Bloom has a symbolic connection to the florin. A flower (or bloom) was often incorporated on one face of the florin. However, the 1904 florin had an image of Britannia above the waves. Bloom, who is our Odysseus, a lover of water, similarly masters the waves and doesn't drown in them like the rest of his crew. Bloom’s connection to the water can even be seen in his childhood nickname “mackerel.” Mackerels don’t drown in water; they integrate into its circulation and flow. Bloom recalls in “Ithaca” how he once notched a florin and sent it into circulation to see if it ever returned to him (it didn’t). Osteen sees the florin, when paid by Dodd, as a symbol of Jewish greed, but in the hand of Bloom, the florin demonstrates the imperfection of circulation and that it doesn’t guarantee a return. The florin is connected to rescue from drowning as well. The florin was given as a measly reward for saving Dodd’s son from drowning, but Bloom, florin incarnate, will be the one who saves Simon’s son from drowning like his father.

Further Reading:

Adams, R. M. (1962). Surface and Symbol: The Consistency of James Joyce’s Ulysses. New York: Oxford University Press.

Boyle, R. (1965). A Note on Reuben J. Dodd as "A Dirty Jew". James Joyce Quarterly, 3(1), 64-66. Retrieved May 25, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25486544

Casey, N. ( 2016 Jun. 16). 'My father's Jewish cousin Reuben Dodd appeared in Ulysses' - Norah Casey on her connection to Joyce. The Irish Independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.ie/entertainment/books/my-fathers-jewish-cousin-reuben-dodd-appeared-in-ulysses-norah-casey-on-her-connection-to-joyce-34807361.html

Cheyette, B. (1992). "Jewgreek is greekjew": The Disturbing Ambivalence of Joyce's Semitic Discourse in "Ulysses". Joyce Studies Annual, 3, 32-56. Retrieved May 4, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/26283605

Davison, N. R. (1998). James Joyce, Ulysses, and the Construction of Jewish Identity: Culture, Biography and ‘the Jew’ in Modernist Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/rp9ctrt

Ellmann, R. (1959). James Joyce. Oxford University Press.

McCarthy, P. (1984). The Case of Reuben J. Dodd. James Joyce Quarterly, 21(2), 169-175. Retrieved May 25, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25476578

O’Connor, U. (2012 Feb 12). Ulick O'Connor: Real-life 'Ulysses' character who caused a literary stir. The Irish Independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.ie/opinion/analysis/ulick-oconnor-real-life-ulysses-character-who-caused-a-literary-stir-26820766.html

Osteen, M. (1995). The economy of Ulysses: making both ends meet. New York: Syracuse University Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yycf2ar5