The Language of the Outlaw: John F. Taylor's Speech in "Aeolus"

“But though the Irish are eloquent, a revolution is not made of human breath and compromises.” - James Joyce, “Ireland, Island of saints and Sages”, 1907

To listen to a discussion of this topic, check out the podcast episode here and here.

In the closing pages of “Aeolus,” Ulysses’ seventh episode, the men gathered in the offices of the Evening Telegraph share a smoke as they recite their favorite bits of oratory. In response to attorney Seymour Bushe’s eloquent courtroom defense (as recited by disgraced attorney J.J. O’Molloy), the eccentric professor MacHugh offers up a speech given by attorney John F. Taylor. It’s the third and final example of rhetoric presented in “Aeolus,” and like the two previous examples (Bushe’s legal defense and Dan Dawson’s doughy discourse), Taylor’s speech is an example of one of Aristotle’s three styles of oratory: the deliberative, which is employed for political, hortative or advisory speech.

Out of the entirety of Ulysses, this is the only passage of which James Joyce produced a voice recording. Joyce said he chose this passage because it is “declamatory and therefore suitable for recital.” There was no market for audio novels in 1924 when he and Sylvia Beach preserved Joyce’s voice in black resin; they were merely a novelty. Only 30 copies of the record were pressed, most of which are now lost (though not all), but one must wonder if Taylor’s oratory also held a special place in the Artist’s heart beyond its declamatory voice.

A MAN OF HIGH MORALE

Professor MacHugh introduces Taylor’s speech:

“The finest display of oratory I ever heard was a speech made by John F Taylor at the college historical society. Mr Justice Fitzgibbon, the present lord justice of appeal, had spoken and the paper under debate was an essay (new for those days), advocating the revival of the Irish tongue.”

The scene described by MacHugh is based on real events, with John F. Taylor and Gerald Fitzgibbon butting heads in a battle of wits on the question of reviving the Irish language. The Gaelic Revival was in full swing at the time, and the revival of the Irish language was mainly supported by Catholics and Nationalists, so this was a political argument as much as a cultural one. Legend has it that a young university student by the name of James Joyce attended the event, retained parts of the speech in his prodigious memory, and immortalized Taylor’s moving rhetoric in Ulysses.

The Honorable Society of King's Inns, Dublin

The exact date of the debate is itself up for debate. Joyce biographer Richard Ellmann wrote that Joyce attended the debate at the Law Students’ Debating Society at King’s Inns in Dublin, October 1901, and most scholars have accepted this as fact over the ensuing decades. However, Taylor and Fitzgibbon’s debate was such a hit, that they reprised their performance in November 1901, this time at the University College Debating Society. There is no corroborated evidence that Joyce attended either, though clearly Joyce was familiar with this particular debate. However, Joyce was a student at University College Dublin in 1901 but did not frequent the Law Student’s Debating Society. Additionally, another attendee of the November debate mentioned that he had seen “Dreamy Jimmy” and J.F. Byrne (a friend of Joyce’s) in attendance that night.

MacHugh reports that the debate was held in the “college historical society,” which doesn’t quite match either of the two 1901 venues. That’s alright - this allows Joyce to fictionalize this event as much as the novel demands. Mr. Justice Fitzgibbon, descended from a long line of supreme court judges, was indeed the lord justice of appeal, one of the highest ranked judges in Ireland. Scholar So Onose describes Fitzgibbon as an “intractable Unionist and Protestant” who was greatly opposed to the Nationalism so popular among educated, young Catholics in the audience at the UCD debate. Fitzgibbon was happy to pour “the proud man’s contumely upon the new [Gaelic Revival] movement.”

Irish Home Rule, or devolved government, was also popular amongst the young students, but Fitzgibbon’s plan was to convince them to become good Unionists not through the pouring of contumely (meaning scorn), but through attempting “to kill Home Rule with kindness,” as Onose puts it. Rather than heap scorn on the Nationalists’ passions, Fitzgibbon hoped to convince them that the Irish language wouldn’t do them any good, and that the Tories would treat them with so much dignity and respect that they didn’t really need silly old Home Rule after all.

Another name that pops up in MacHugh’s preamble is Nationalist politician and attorney Tim Healy. I’ve written previously about Joyce’s personal animus against Healy. Though Healy was quite a prominent Irish political figure of the time, and quite an accomplished orator, his name only appears in Ulysses in passing, such as in this passage in “Aeolus”:

“—He is sitting with Tim Healy, J. J. O’Molloy said, rumour has it, on the Trinity college estates commission.

—He is sitting with a sweet thing, Myles Crawford said, in a child’s frock. Go on. Well?”

Editor Myles Crawford dismisses Healy as nothing more than “a sweet thing in a child’s frock” before demanding MacHugh “go on.” Healy appears seated beside conservative Justice Fitzgibbon, opponent of Home Rule. Joyce’s grudge against Healy is due to his prominent role in the downfall of Charles Stewart Parnell, promoter of Irish Home Rule and a favorite of Joyce. The juxtaposition of Fitzgibbon and Healy, I believe, is to show Healy as an enemy of Irish Home Rule and a friend of the Fitzgibbons of the world. In fact, the other two mentions of Healy in Ulysses also pair him with Fitzgibbon. From “Oxen of the Sun”:

“Over against the Rt. Hon. Mr Justice Fitzgibbon’s door (that is to sit with Mr Healy the lawyer upon the college lands)”

And in “Circe,” he appears as part of the “hue and cry” that attack Bloom:

“...Lenehan, Bartell d’Arcy, Joe Hynes, red Murray, editor Brayden, T. M. Healy, Mr Justice Fitzgibbon, John Howard Parnell, the reverend Tinned Salmon…”

IMPROMPTU

Professor MacHugh prepares his rapt audience for his recitation of Taylor’s oration just as dramatically as he delivered his preamble on Fitzgibbon. The narration describes MacHugh as speaking in a “ferial tone,” an obscure reference to be sure, and according to Harald Beck on James Joyce Online Notes, a misunderstood one. A ferial tone, or tonus ferialis, is an uninterrupted monotone used to deliver ordinary, weekday prayers during a Catholic Mass. This contrasts with a festal tone (tonus festivus), which is also a monotone but with occasional changes of tone. A festal tone would be used more appropriately for delivering such lofty oratory as Taylor’s. Beck interprets Stephen Dedalus as the narrator here, ironically casting MacHugh’s tone as ferial. Basically, it’s a sick Latin burn.

Curiously, MacHugh directs his opening remarks to J.J. O’Molloy, but there’s a plausible reason. Taylor and Fitzgibbon’s debate was covered in detail by the Dublin press, despite MacHugh’s assertion that “there was not even one shorthandwriter in the hall.” Both the Freeman’s Journal and the Irish Daily Independent not only reported on the debate and its content, but also on the attendees. Both newspapers reported John O’Mahony, B.L., O’Molloy’s real-life counterpart, in attendance. MacHugh says to O’Molloy, “Taylor had come there, you must know, from a sickbed.” Indeed, O’Molloy must know this as he was in the audience.

Taylor did arrive from his sickbed to deliver his extemporaneous, or impromptu, remarks. Gifford and Seidman’s Ulysses Annotated, states simply, “Taylor’s speech was never written out or taken down.” Gifford and Seidman acknowledge that the speech was covered in the Freeman’s Journal, though the coverage was not as “pallid” as their annotation states, a description originating in Richard Ellmann’s biography of Joyce.

FROM THE FATHERS

MacHugh gives a detailed recitation of Taylor’s speech - the most comprehensive of the three samples of rhetoric present in “Aeolus” - silently interrupted by Stephen’s own annotations. Taylor deftly analogizes the plight of the Israelites held in bondage in Egypt with that of the Irish as imperial subjects of the English. This analogy did not originate with Taylor, however, and was quite a common parallel employed by Nationalists and Home Rulers in those days.

Stephen riffs on this Mosaic imagery:

“Nile.

Child, man, effigy.

By the Nilebank the babemaries kneel, cradle of bulrushes: a man supple in combat: stonehorned, stonebearded, heart of stone.”

Michelangelo’s Moses, in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome

“Child, man, effigy” describes the three phases of Moses - as a child among the bulrushes, a man leading his people to the Promised Land, and post-mortem as an unchanging effigy in the Vatican or wherever. Stephen’s comment calls to mind J.J. O’Molloy’s recitation of Seymour Bushe’s defense of Samuel Childs, in which he used an especially eloquent description of Michelangelo’s sculpture of Moses to help acquit the possibly-innocent Childs. Stephen can’t help but notice that the other men are soft on a speech with Moses in it. The images of “babemaries kneeling beside the Nile, placing infant Moses amongst the bulrushes to spare him from a cruel pharaoh, is a callback to his thoughts beside the sea back in “Proteus”:

“The two maries. They have tucked it safe mong the bulrushes. Peekaboo. I see you.”

Stephen’s thoughts in “Proteus” are darkly irreverent as he likens two midwives giving a stillbirth to waves with Moses’ mother and her sister Miriam trying to spare the infant Moses’ life in Exodus. This is maybe the darkest peekaboo of all time. Stephen employs that same irreverence and skepticism to Taylor’s words. Moses is eternal and powerful, yes, but perhaps the “stonehorned, stonebearded” patriarch of old also bears a “heart of stone.”

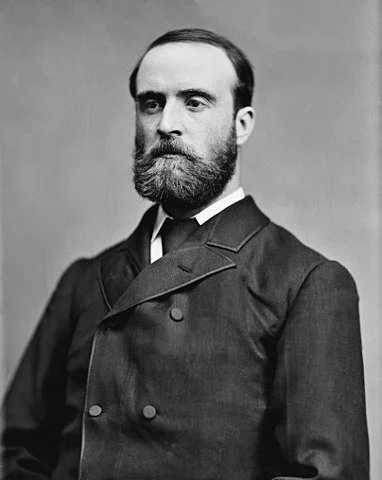

Charles Stewart Parnell

Stephen’s dubiousness toward Taylor's speech is as much political as it is religious. Joyce’s most-revered Charles Stewart Parnell, the double-crossed hero of Home Rule, was frequently compared with Moses in this era. Parnell was, after all, a man who fought for the rights of his people against an immovable behemoth, only to perish without ever setting foot in the Promised Land for which he sacrificed so much. The Parnell-Moses parallel was particular to turn-of-the-century Irish politics, as by 1922 it would be replaced with the new narrative of a liberation based on self-sacrifice that was distinctly New Testament. In any case, the Mosaic imagery so resonated with Joyce that in a 1912 article entitled “The Shade of Parnell”, he described how Parnell:

“... like another Moses, led a turbulent and unstable people from the house of shame to the verge of the Promised Land.”

The identification of the subjugation of the Irish with that of the Jews runs deeper than mere political analogy, though. As far back as the 17th century, Irish writers told of how the Irish were not just similar to the ancient Israelites, but were, in fact, the descendants of a lost tribe of Israel who had settled on the fringes of Europe. (I’ve explored this idea in-depth in a blog post entitled “Was Leopold Bloom Phoenician?” which you can read here.) To make a long story short, some writers contended that the mythical founders of Ireland, Milesians, were Phoenicians, an ancient Semitic group that lived in the Near East. If the Irish were connected to Israel through the Milesians, then they too were also among God’s chosen people. In Joyce’s era, this empathy for the struggle of the Israelites was invoked in speeches by Nationalist figures such as Michael Davitt, as well as by Parnell himself. The Jews were held up by Irish Nationalists as “brothers in a common struggle” and even “brothers in sorrow.” And just as Taylor makes a case for the revitalization of the Irish language, Zionists in the early 20th century were pushing for the revival of Hebrew. In 1892, Gaelic Revivalist and future president Douglas Hyde wrote:

“...for an educated Irishman… to be ignorant of his own language would make it at least as disgraceful as for an educated Jew to be quite ignorant of Hebrew.”

This empathy and kinship was extended to Biblical Jews but not necessarily to contemporary, living Jews. Antisemitism was common in many Irish Liberal circles. This ambivalence had a long history in Britain, as well, but politically allowed Irish Catholics to position themselves in line with the ancient history of Judaism as members of the oldest church, a palatably Christianized version of the Chosen People. Amongst our characters in Ulysses, this quality can be seen in how moving these men find Taylor’s speech comparing themselves to the Israelites being lead home by the exalted Moses, while at the same time they are dismissive and occasionally outright cruel to Leopold Bloom, the sole Jewish member of their peer group.

This Mosaic imagery didn’t originate with John F. Taylor, then, nor did it originate with Joyce. As mentioned above, Joyce is likely to have attended Fitzgibbon and Taylor’s debate in 1901, and many commentators attribute the detailed quotations found in “Aeolus” to Joyce’s own superior memoria, the skill of memory employed by master orators. Joyce’s memoria, though impressive, likely had a fairly healthy assist.

Joyce scholars have long held that Taylor’s speech went unrecorded in its day, but this isn’t quite accurate. It was printed in its entirety in the press the following day. Ellmann as well as Gifford and Seidman describe the critical response in 1901 as “pallid,” which also seems inaccurate as The Freeman’s Journal recounted it in fairly glowing terms. Taylor’s first speech was improvised and delivered straight from his sick bed, so it may not have been his peak performance, but he was able to polish the speech for their repeat performance in November, the one that Dreamy Jimmy may have attended.

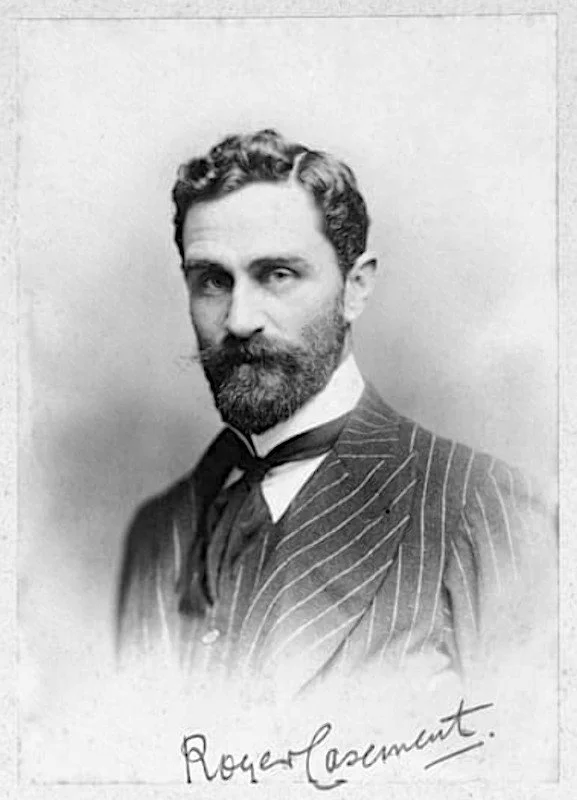

Roger Casement, c. 1910

Taylor’s speech lived on in a pamphlet entitled “The Language of the Outlaw”, which was privately printed in a run of 5-10,000 copies and circulated in 1904 or 1905, mainly in the North of Ireland. Given the ephemeral nature of the reproductions of Taylor’s 1901 debate performance, it’s believed that this is the version that Joyce would have been most familiar with. Though the pamphlet was printed anonymously, it’s now believed that Irish revolutionary Roger Casement was the pamphlet-maker. Taylor died in 1902, but his speech took on a life of its own after its creator’s untimely passing. This explains O’Molloy’s remark that, “he died without having entered the land of promise.”

Casement’s version is a revision that omits, for example, Taylor’s focus on the purported purity of Irish and reframes the argument about Irish as the cultural property of a down-but-not-defeated people. The version found in Ulysses is not taken purely from Casement’s pamphlet, either. According to Onose, Joyce punched up Taylor’s speech to add a greater degree of “Parnellite animus,” as he felt that “Taylor lacked precisely this bold, insurrectionary spirit of Parnellism.” Casement’s revision might be a 7 or 8 out of 10, but Joyce was shooting for 11. Let’s contrast Casement’s closing paragraph with Joyce’s. Casement’s reads:

“And… if Moses had listened to these arguments, what would have been the end? Would he ever have come down from the Mount, with the light of God shining on his face and carrying in his hands the Tables of the Law written in the language of the outlaw?”

Whereas Joyce’s reads:

“—But, ladies and gentlemen, had the youthful Moses listened to and accepted that view of life, had he bowed his head and bowed his will and bowed his spirit before that arrogant admonition he would never have brought the chosen people out of their house of bondage, nor followed the pillar of the cloud by day. He would never have spoken with the Eternal amid lightnings on Sinai’s mountaintop nor ever have come down with the light of inspiration shining in his countenance and bearing in his arms the tables of the law, graven in the language of the outlaw.”

Joyce’s Moses

Casement may have been a better revolutionary, but Joyce was by far the better poet. Joyce adds rhetorical flourishes such as repetition (“...had he bowed his head and bowed his will and bowed his spirit…”) and assonance (“arrogant admonition”). Joyce’s Moses has a “countenance” rather than a “face,” and his tables are “graven” rather than “written.” In the Jewish fashion, Joyce’s version avoids referring directly to “God,” rather his Moses encounters “the Eternal amid lightnings on Sinai’s mountaintop.” Joyce’s version more prominently emphasizes the oppression of the Jews, referencing Moses’ bowed head, and their entrapment in the “house of bondage” (a phrase also favored by Leopold Bloom). Richard Ellmann wrote that Bloom’s description of his childhood seders and his malapropism about the house of bondage is actually a callback to Taylor’s speech rather than the other way round, since the Haggadah is read from right to left, and so “Aeolus” can also be interpreted from right to left, or back to front. Thus, Taylor’s speech would precede Bloom’s thoughts on Passover.

For all its fire and poetry, MacHugh’s recitation is not met with rapturous applause:

“He ceased and looked at them, enjoying a silence.”

Their reaction is simply silence. The silence could be due to disinterest, but it could also be awe at the oratory. The newsmen don’t offer up much comment, but on the other hand, MacHugh is able to get out his whole recitation without interruption (unlike Crawford’s story about Ignatius Gallaher), he gets through far more than O’Molloy’s recitation of Bushe’s defense, and no one mocks Taylor like they did Dawson.

OMINOUS - FOR HIM!

Stephen offers a rebuttal, though it is also silent:

“Gone with the wind. Hosts at Mullaghmast and Tara of the kings. Miles of ears of porches. The tribune’s words, howled and scattered to the four winds. A people sheltered within his voice. Dead noise. Akasic records of all that ever anywhere wherever was. Love and laud him: me no more.”

Stephen is initially swayed by Taylor’s eloquence, just like with Bushe’s. He is even tempted to follow in Taylor’s footsteps (“Noble words coming. Look out. Could you try your hand at it yourself?”) just as Moses was tempted by the fleshpots of Egypt. Stephen is quick to realize that words are merely wind, likely to blow away as soon as they’re uttered only to twist and turn weathercocks in their gusts. Stephen’s true aspiration is to be a weaver of the wind.

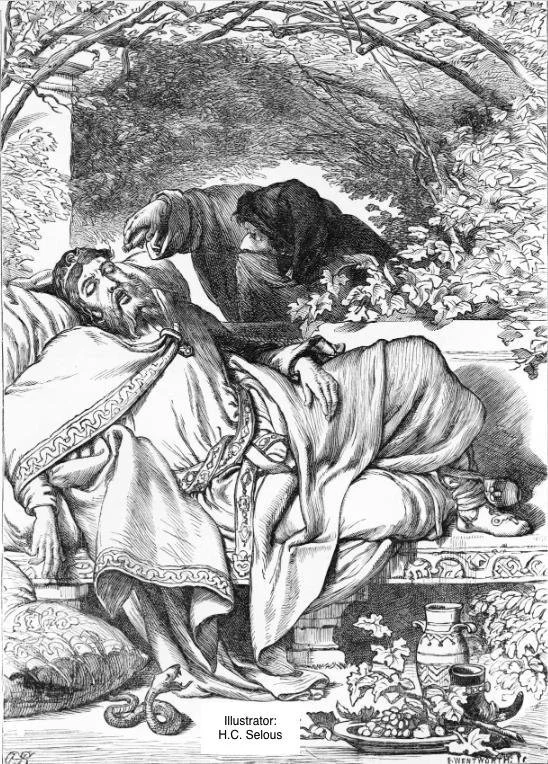

Poison poured in the ear of King Hamlet

Perhaps via the Akashic records, Stephen calls to mind the Liberator Daniel O’Connell’s famous mass rallies at Mullaghmast and the Hill of Tara. While they attracted possibly millions of devotees, eager to hear “the tribune’s words,” they were ultimately “dead noise” in Stephen’s mind. Prime Minister Robert Peel declared these rebellious meetings illegal, and O’Connell capitulated rather than push back. Like Taylor’s compromised liberalism, O’Connell was not radical enough in his resistance. He comforted the throngs with his words, but they were filled with false hope, a poison for the ears of his listeners. Taylor’s nationalistic eloquence is similarly hollow. As a spoken riposte, Stephen has a much better suggestion for those assembled:

“—Gentlemen, Stephen said. As the next motion on the agenda paper may I suggest that the house do now adjourn?”

Onose believes that this is an allusion to Parnell's tactic of adjourning meetings prematurely in order to force the English MPs to focus on Irish issues. In 1877, Parnell and six colleagues managed to hold the floor for more than twenty hours until the English opposition capitulated. The newsmen are far more energized by Stephen’s invitation to adjourn to the pub than by MacHugh’s nationalistic rhetoric. O’Madden Burke even jousts with an umbrella-sword, perhaps accepting a role as a brother-in-arms alongside Stephen’s “ash sword.”

Ultimately, if Taylor’s words lack the power to move these men, booze certainly motivates them:

“—That it be and hereby is resolutely resolved. All that are in favour say ay, Lenehan announced. The contrary no. I declare it carried. To which particular boosing shed...? My casting vote is: Mooney’s!”

How similar were the situations of the Irish and the Israelites, really? The Hebrew language seemed to be widely spoken in ancient Egypt and the pharaohs weren’t necessarily trying to impose their own language or culture on the Israelites. Taylor’s speech is indeed moving, but it still succumbs to the perils of Dawson and Bushe. Ellmann points to “a desire not to live in the present but to live in a petrified past and speak a dead language” and that Bloom’s malapropism about the Exodus story (“out of Egypt and into the house of bondage”) could also be the fate of the Irish if they are swayed too easily by pretty words. In James Joyce’s Ulysses: Critical Essays, M.J.C. Hodgart lays out how Taylor’s argument lacks logic, relying too heavily on argumentum ad passiones (an appeal to emotion), and never provides adequate evidence to prove his syllogism that the Irish language is the historical successor of Hebrew. His argument also leans on argumentum ad hominem (an appeal to the man), as Taylor’s good character is touted early on by MacHugh and Crawford. The esteem of the man lends esteem to his words. Author of Ulysses: A Study Stuart Gilbert wrote that Taylor’s speech is an example of:

“...the manner in which eloquence aided by the rhetorical device of a far-fetched, not to say false, analogy, can produce conviction in the listener’s mind.”

Despite all this, I still love re-reading Taylor’s speech. It may not present evidence to support its premise, but it plays to my natural biases, so I am predisposed to find it convincing. I already believe Taylor’s buried premise - that the Irish language must be revived - and therefore can be easily swayed by his eloquence since I don’t need a solid proof of that statement in order to find his argument compelling. While the language debate may seem relatively benign on its surface, pretty words akin to Taylor’s eventually contributed in part to armed revolt in Ireland. Whether or not you see that as positive may be due to your own biases as well. Words may be woven of wind, but any breeze has the potential to become a gale.

Further Reading:

Beck, H. Undertones of the sacred offices. James Joyce Online Notes. Retrieved from https://www.jjon.org/joyce-s-words/undertones

Bender, A. (2007). The Language of the Outlaw: A Clarification. James Joyce Quarterly, 44(4), 807–812. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25571086

Bender, A. (2015). Israelites in Erin: Exodus, Revolution, and the Irish Revival. Syracuse University Press.

Casement, R. (2004). The Language of the Outlaw. New England Review (1990-), 25(1/2), 155–158. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40244373

Crowley, R. John O’Mahony and the Language of the Outlaw. James Joyce Online Notes. Retrieved from https://www.jjon.org/jioyce-s-people/john-omahony-2

Cheyette, B. (1992). "Jewgreek is greekjew": The Disturbing Ambivalence of Joyce's Semitic Discourse in "Ulysses". Joyce Studies Annual, 3, 32-56. Retrieved May 4, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/26283605

Davison, N. R. (1998). James Joyce, Ulysses, and the Construction of Jewish Identity: Culture, Biography and ‘the Jew’ in Modernist Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/rp9ctrt

Ellmann, R. (1972). Ulysses on the Liffey. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.65767/2015.65767.Ulysses-On-The-Liffey_djvu.txt

Gilbert, S. (1955). James Joyce’s Ulysses: a study. New York: Vintage Books. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.124373/page/n3/mode/2up

Hodgart, M.J.C. (1974). Aeolus. In C. Hart & D. Hayman (eds.), James Joyce’s Ulysses: Critical essays (115-130). Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yy2gpfhs

Joyce, J. (1912). The Shade of Parnell. In E. Mason & R. Ellmann (eds.), The Critical Writings of James Joyce, (223-228). Cornell University Press.

Joyce, J. (1924). Ulysses [Speech audio recording]. Shakespeare and Co. Retrieved from https://www.themorgan.org/exhibitions/online/ulysses/joyces-recording-ulysses

Onose, S. (2016). “a great future behind him”: John F. Taylor’s Speech in “Aeolus” Revisited. European Joyce Studies, 24, 46–62. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44871385

Slote, S., Mamigonian, M., and Turner, J. (2022). Annotations to James Joyce's Ulysses. Oxford University Press.

Smith, E. D. (2004). How a Great Daily Organ Is Turned out: “Aeolus,” “Techne,” and the Recording of “Ulysses.” James Joyce Quarterly, 41(3), 455–468. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25478071

Sultan, S. (1961). Joyce’s Irish Politics: The Seventh Chapter of “Ulysses.” The Massachusetts Review, 2(3), 549–556. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25086710

Taylor, John Francis | Dictionary of Irish Biography. (n.d.). Retrieved October 18, 2022, from https://www.dib.ie/biography/taylor-john-francis-a9618

Williams, E. (1986). Agendath Netaim: Promised land or waste land. Modern Fiction Studies, 32(2), 228-235. Retrieved February 22, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/26281745

King’s Inns image source