The House of Keyes

“Love laughs at locksmiths.” -Gerty MacDowell

To listen to a discussion of this topic, check out the podcast episode here.

There’s a parallel universe where, rather than becoming one of the great novelists, James Joyce became a master advertiser and propagandist on par with Edward Bernays. Consider the following tableau:

“-- a colored picture… representing two young ladies… seated at a table on which a book stands upright, with title visible, and underneath the picture three lines of simple dialogue, for example:

Ethel: Does Cyril spend too much on cigarettes?

Doris: Far too much.

Ethel: So did Percy (points) -- until I gave him Zeno.”

“Zeno” in this case refers to the novel The Confessions of Zeno, written by Joyce’s friend and model for Leopold Bloom, Italo Svevo. Joyce thought it imperative that Svevo had some snappy ads to promote his forthcoming novel, and this is what he proposed in a letter to Svevo. Like his famous protagonist, Joyce had a fascination with the power of advertising. There is an artistry to the best ads. Only a master can create something deceptively simple yet powerful enough to grip the human subconscious through a multitude of layered meanings.

Enter Leopold Bloom, master ad canvasser.

In the opening pages of “Aeolus”, Ulysses’ seventh episode, we find Bloom in the printshop of the Freeman’s Journal, explaining his latest dynamite design to foreman Joseph Nannetti. While more industrious than his colleagues in the office, Nannetti is phlegmatic in the face of Bloom's creative exuberance. Nannetti “[moves] his scratching hand to his lower ribs and [scratches] there quietly” while Bloom gushes about his clever design for wine, tea and spirit merchant, Alexander Keyes. After hearing Bloom out, Nannetti laconically replies, “We can do that.... Let him give us a three months’ renewal.”

Joseph Nannetti, Sr.

Joseph Nannetti was indeed the foreman printer at the Freeman’s Journal during this era. In real-life there were actually two Nannettis, a father and son both called Joseph. The character in “Aeolus” is a melange of the two. Nannetti the Younger was similar to the foreman printer portrayed in Ulysses, while Nannetti the Elder was a distinguished politician, as Bloom hints in “Aeolus.” Bloom addresses Nannetti as “councillor,” as he had been elected as a Dublin city councillor in 1898. Bloom also describes him as “member for College Green,” since Nannetti had been elected as the Member of Parliament for that constituency in 1900. Bloom even correctly guesses Nannetti’s political future when he thinks, “Soon be calling him my lord mayor;” Nannetti served two terms as Lord Mayor of Dublin between 1906-1908.

Alexander Keyes was a real tea, wine and spirit merchant in Dublin in Joyce’s era, though less keen to advertise in the Freeman’s Journal than his fictional counterpart. Keyes ran very few ads in the newspapers of the day, perhaps because the experience was a bit of a fiasco. Keyes bought a month’s worth of ads in the weekly Irish Figaro in 1896. The first week’s ad promoted the business of Alexander “Kayes.” While this orthographical error was corrected in the subsequent editions, elsewhere in the ad the word “warehouseman” came out “warehousema.” Unsurprisingly, Keyes did not renew his ad with the Figaro. It seems Keyes didn’t advertise with any of the Dublin dailies, including the Freeman’s Journal, or The Kilkenny People, as Bloom says in Ulysses.

Keyes’ Figaro ad wasn’t nearly as snazzy as the one that Bloom cobbles together in Ulysses, lacking that signature crossed keys logo. The Figaro ad was text-only (as are all the other ads sharing the page). Bloom pushes for “a little par calling attention,” meaning a short paragraph (“just a little puff”) on a separate page promoting Keyes’ business, but there was no puff piece anywhere in the Figaro. If you’d like to see a reproduction of Keyes’ Figaro ad, you can find it in this article. In the end, it’s nice to see Keyes’ ad given immortality in Ulysses after being so consistently botched in the real world.

One more note about Keyes - he and a young James Joyce crossed paths in life, though at least Keyes was surely unaware of it. Keyes was one of the jurors on the Samuel Childs murder trial, which J.J. O’Molloy discusses later in “Aeolus”. Joyce, who was fascinated with legal proceedings, sat in the gallery of Childs’ trial and took notes. Though the Childs murder trial is mentioned prominently in “Aeolus,” Keyes’ participation didn’t make it into the novel.

If Bloom ever manages to get Keyes’ ad to print, it would be worthy of at least four months renewal. It’s truly a work or art, worthy of Bernays or Draper. On its face, it’s an obvious pun on the name Keyes, but there are multiple levels of meaning concealed in those simple crossed keys. Bloom intends it to have a political meaning - “innuendo of home rule.” The crossed keys also conjure religious, economic and personal meaning for Bloom and his peers. Mark Osteen describes how Bloom’s quest for “renewal” of this ad mirrors his personal quest for renewal of home. Like Odysseus, his hopes for renewal (in this case, of Keyes’ ad) are ultimately dashed by Aeolus/Crawford. Even before Crawford’s denial, Keyes had only offered Bloom a partial renewal. Unlike Odysseus, Bloom never achieves his symbolic renewal, mentally noting it as an “imperfection” in “Ithaca”. What could obtaining renewal through an emblem of two keys crossed in saltire (to use heraldic language) offer our gentle Irish Odysseus?

House of Keys seal

Let’s begin with that “innuendo of home rule,” a hot topic in Bloom’s Dublin and in Joyce’s works generally. M.P. Charles Stewart Parnell led a popular campaign for Irish home rule, or devolved government within the United Kingdom, in the late 19th century before scandal ended his political career. In 1904, Irish home rule was still an unachieved political dream for many. The Isle of Man, on the other hand, had achieved limited home rule beginning in the 1860’s, with their lower house of parliament known as the House of Keys. Bloom’s crossed keys could be a homey little reminder to attract Manx tourists like he suggests, or it could be a subtle call for the Irish to wrest a bit of power from London. Ireland’s desire for political home rule parallels Bloom’s own desire to rule his own home in the face of Blazes Boylan’s incursion. Poor Bloom has forgotten his key in his other pair of trousers and has lost the power of the keyholder, losing control of the Keys of House, at the very least.

Bloom has subconsciously integrated crossed keys as a symbol of political power, as is evident when they reappear as the keys to the city of Dublin in “Circe.” In this scene, as Bloom is exalted by his fellow Dubliners, Alexander J. Keyes steps from the crowd to ask, “When will we have our own house of keys?” Bloom, like any politician, real or hallucinated, offers up a litany of pledges, vowing to bring all people together in unity, ending with, “Free money, free love and free lay church in a free lay state.”

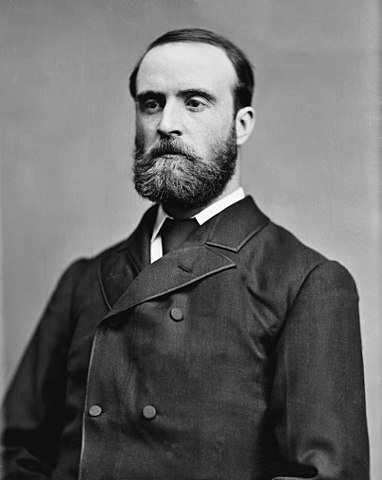

Charles Stewart Parnell

Osteen points out that the crossed keys could instead symbolize a double cross, a symbolic betrayal rather than renewal. During the above scene in “Circe”, the crowd turns on Bloom after his litany of promises. Parnell’s crusade for home rule evaporated when the Church disavowed him, which was seen as betrayal by his supporters. The tea that Keyes sells is produced on the backs of those most exploited by the British Empire, the same Empire exploiting the Irish. In this example, the crossed keys are stripped of political potency by the immediacy of commerce. Economics takes priority over any overt political ideal because, ultimately, Keyes is in business to sell tea, wine and spirits, not idealism. The crossed keys can offer nothing more than a vague innuendo unlikely to lead to bold political action against the established order. No one with real power would attempt to prevent Keyes including such an insinuation in his ad because there’s zero chance that anyone would be moved to revolution by such a subtle symbol.

Joyce frequently portrays the Irish in a state of paralysis in their occupied country. They’re happy to sit around a pub or a committee room and remember the good ol’ days, but they do very little to change their lot in life. In fact, they are often complicit in the very system that oppresses them. Bloom goes to Dillon’s auction house to find Keyes and get his renewal. We learn in “Wandering Rocks” that the Dedalus sisters are also at Dillon’s selling their family’s furniture in order to survive. The poor pawn their most meager possessions to those enriched by imperial trade. Even Bloom will benefit financially from Molly’s concert tour with Blazes Boylan, though it makes him a cuckold.

The Coat of Arms of Vatican City

The emblem of crossed keys also evoke the coat of arms of Vatican City, a seat of entrenched power with immense influence over Ireland. Also known as the Keys of Heaven, this emblem is made of two keys, one silver and one gold, crossed diagonally on a red shield. The keys are a symbol of St. Peter, as is stated in Matthew 16:19:

“And I will give unto thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt bind on earth shall be bound in heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.”

Given Bloom’s spotty track record with Catholicism, we can assume that he doesn’t recognize this symbol of papal supremacy. However, Joyce expects us readers to pick up on it. The red background is even incorporated when Bloom is given the keys to the city in “Circe”:

“The keys of Dublin, crossed on a crimson cushion, are given to him.”

When interpreting the crossed keys, Bloom considers a political interpretation in the morning but concludes with a religious one at the end of the night, parenthetically describing Keyes’ ad as “Urim and Thummim” in his recap of the day in “Ithaca.” The Urim and Thummim are two stones, one black and one white, kept in the breastplate of the High Priest. From Exodus 28:30:

“Also put the Urim and the Thummim in the breastpiece, so they may be over Aaron’s heart whenever he enters the presence of the LORD. Thus Aaron will always bear the means of making decisions for the Israelites over his heart before the LORD.”

There are a lot of unknowns when it comes to the Urim and Thummim, but some believe they can be used for divination. The stones would be placed in a bag and drawn to answer “yes” and “no” questions. The symbolic meaning of the Urim and Thummim is likewise uncertain, though there are plenty of interpretations, such as lights and perfection, guilt and innocence, and revelation and truth. Their divinatory power means they are able to reveal the will of God to the user. Their dual nature and connection to the divine correspond the Urim and Thummim with the Keys of Heaven, which confer Paradise only by the will of God and symbolize the duality of absolution and excommunication.

The crossed keys symbolize both the sacred and temporal then, allowing Keyes’ products to promise the consumer renewal in their earthly home in the form of home rule and the salvation of their everlasting soul in the afterlife. Alexander Keyes is a “spirit merchant,” after all, just like a pope or high priest. Keyes’ ad hints at the ability of his product to open the gates of heaven, an “abode of bliss,” if you will. There is an elitism to this consumerist route to spiritual restoration, though. Only those who can pay their way can access Keyes’ Keys of Heaven. Like the Christian Heaven, not everyone is worthy of entry into Keyes’ Paradise, and those who can pay their way have easier access than those who cannot.

Keys confer power to the keyholders throughout Ulysses. However, Patrick White sees these keyholders as scions of a diminished power. Joyce’s characters in Ulysses are living in a period of disintegration in line with Giambattista Vico’s cyclical view of history. Bloom and friends are less potent reincarnations of the lofty figures of a bygone age of heroes, thus Odysseus has become a low-level ad canvasser in Dublin. (We discussed Vico’s ideas in more detail here). In the case of Keyes’ ad, White states that, “... the keys from the Papal arms of the previous divine age now participate for Alexander J. Keyes in the religion of the period of disintegration, whose god is Mammon.” The people that Bloom and Stephen Dedalus meet throughout the course of June 16th are also diminished forms of ancient ideals. In Ulysses’ first episode, “Telemachus”, we meet Buck Mulligan, a sarcastic blasphemer who, by the end of the episode, holds the key (and by extension the power) to the domain of our diminished prince, Stephen Dedalus, who is totally dispossessed.

Peter Paul Rubens, Saint Peter, 1610-1612

Bloom must contend with his own set of keyholders, each in possession of a diminished version of St. Peter’s Keys of Heaven. Consider John O’Connell, caretaker of Glasnevin Cemetery. When we first meet O’Connell in “Hades”, he is “puzzling two long keys at his back.” Bloom takes notice and even connects O’Connell’s keys with Keyes’ ad:

“Mr Bloom admired the caretaker’s prosperous bulk. All want to be on good terms with him. Decent fellow, John O’Connell, real good sort. Keys: like Keyes’s ad: no fear of anyone getting out. No passout checks.”

Bloom knows that O’Connell holds both keys and power (“all want to be on good terms with him”), but he doesn’t know the depth of the power. O’Connell is also a spirit merchant of sorts, providing the souls of his customers a comfortable berth into the next life. Osteen describes him as a “terrestrial analogue of St. Peter’s.” Unlike St. Peter, O’Connell does not preside over Heaven, but instead over an earthly realm of the dead, of grief and putrefaction and corpse-eating rats. Either way, this psychopompic power is still governed by a pair of keys. When O’Connell resurfaces in “Circe”, he calls out the location of Dignam's postmortem digs, revealing O’Connell’s house of death to be a house of keys:

“Burial docket letter number U. P. eightyfive thousand. Field seventeen. House of Keys. Plot, one hundred and one.”

Fast forward to “Aeolus”, where Evening Telegraph editor Myles Crawford lives in a world of memory. We see him “jingling his keys in his back pocket” while reminiscing about his journalistic heroes of the past rather than hunting down any current scoops. After some furtling around, the newsmen prepare to head towards the pub when Crawford asks, “Where are those blasted keys?” He then “fumble[s] in his pocket pulling out the crushed typesheets.” Crawford is a keyholder struggling to locate the source of his power, lost amongst the disorderly typesheets, the tools of his trade.

Caravaggio, The Denial of St. Peter, 1610

Crawford, like Peter, holds the keys to the kingdom, though Crawford’s kingdom is the Evening Telegraph, a newspaper in decline. In a golden age, he might preside as the voice of his city and his people, a St. Peter of the press, guardian of ideas. However, in this Viconian age of disintegration, he represents that era’s voice in the guise of a confused old man, unable to fish his keys out of his pocket, his only motivation an impending pint or two. Bloom approaches St. Peter Crawford in search of renewal (commercial, not spiritual) and is thrice denied, evoking Peter’s denial of Christ in the New Testament.

The two keys that feature most prominently in Ulysses are not those that unlock a home rule parliament, a heavenly gate, or even an ad for spirits. Our protagonists Bloom and Dedalus have found themselves in a state of keylessness, locked out of their respective kingdoms. Bloom twice forgot his keys that morning as he parted ways with Molly for the day, while Stephen consciously left his key with the usurper Buck Mulligan, choosing not to return to their shared Martello Tower.

Keylessness in this case represents disenfranchisement. Stephen and Bloom are locked out of the traditional halls of power due to their outsider status, but we can see they have both surrendered the keys to their domestic lives as well. They are described in “Ithaca” as a “premeditatedly… and inadvertently, keyless couple.” Though they are both keyless, the circumstances of their keylessness are not the same. Bloom is inadvertently keyless, having left his key in his other pair of trousers that morning. His hand “mechanically” goes to the pocket where they ought to be only to be met with an empty pocket. Metaphorically, Bloom’s foreign heritage, Judaism and soft demeanor mark him as an outsider, always the odd man out, whether he would choose that status or not. In “Circe,” Bloom appears as a youth wearing a “gent’s sterling silver waterbury keyless watch,” suggesting that maybe he never had the metaphorical keys at all. It’s fitting that Bloom would search for symbolic renewal in a set of keys.

On the other hand, Stephen “Non Serviam” Dedalus has rejected religion, academia and the literary establishment. Stephen has chosen to relinquish his key to Mulligan in order to strive for power on his own terms. Before Stephen departs Eccles St. for parts unknown, he makes it clear that embarking on this path is his choice, though Bloom doesn’t fully understand:

“He affirmed his significance as a conscious rational animal proceeding syllogistically from the known to the unknown and a conscious rational reagent between a micro and a macrocosm ineluctably constructed upon the incertitude of the void.”

Stephen “proceeds syllogistically” from the known (his current life) to the unknown (whatever comes next) through the incertitude of the void (the front door of 7 Eccles St.). The exit from 7 Eccles St. is a microcosm of the choice that lies before young Dedalus. Macrocosmically, Stephen has additionally “proceeded syllogistically” into the unknown by choosing not to return to the Martello Tower and, if he follows in the footsteps of his Creator, his homeland of Ireland. Stephen has used logic and reason to “fly by the nets” of the paralysis he sees in the society around him. To possess keys to this kingdom is to possess merely the keys to his own jail cell, and thus he forgoes this symbol of power altogether.

Bloom faces the void in a different way, believing:

“That as a competent keyless citizen he had proceeded energetically from the unknown to the known through the incertitude of the void.”

Bloom accepts his keylessness. He may be inadvertently keyless, but not unwittingly so. Entering 7 Eccles St. for him is traversing the void from an unknown, hostile world to a known place of comfort, even with the current disarray of his marriage. I suppose the devil you know is better than the devil you don’t. Bloom views himself as keyless yet competent. He has developed the necessary skills to exist in a society that wasn’t built for him and isn’t quite sure what to do with him. He has adjusted to his lot in life, even if his Keyes-less state stands out as an imperfection in his mind as he drifts off to sleep. Due to his maturity, he can tolerate life’s imperfections in a way that a 22-year-old can’t. The world built by his Creator is a keyless world (after all, there is no key to decipher all of Ulysses’ cryptic secrets).

Further Reading:

Berger, A. P. (1965). James Joyce, Adman. James Joyce Quarterly, 3(1), 25–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25486537

Ellmann, R. (1972). Ulysses on the Liffey. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.65767/page/n39

Gilbert, S. (1955). James Joyce’s Ulysses: a study. New York: Vintage Books. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.124373/page/n3/mode/2up

Gunn, D. P. (1996). Beware of Imitations: Advertisement as Reflexive Commentary in Ulysses. Twentieth Century Literature, 42(4), 481–493. https://doi.org/10.2307/441878

Igoe, V. (2016). The real people of Joyce’s Ulysses: A biographical guide. University College Dublin Press.

Larkin, F. (2019, May 8). James Joyce’s joust with journalism: The Freeman’s Journal in Ulysses’ Aeolus chapter. The Irish Times. Retrieved from https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/james-joyce-s-joust-with-journalism-the-freeman-s-journal-in-ulysses-aeolus-chapter-1.3879908

O’Shea, M.J. (1986). James Joyce and heraldry. Albany: State University of New York Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/y4u57wya

Osteen, M. (1995). The economy of Ulysses: making both ends meet. New York: Syracuse University Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yycf2ar5

Power, M. (1995). Without Crossed Keys: Alexander Keyes’s Advertisement and “The Irish Figaro.” James Joyce Quarterly, 32(3/4), 701–706. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25473669

Tomkinson, N. (1965). Bloom’s Job. James Joyce Quarterly, 2(2), 103–108. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25486488

White, P. (1971). The Key in “Ulysses.” James Joyce Quarterly, 9(1), 10–25. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25486940

Zweifach, B. Aeolus - Modernism Lab. Retrieved from https://campuspress.yale.edu/modernismlab/aeolus/