MEMORABLE BATTLES RECALLED: The Sham Squire and the Boys of Wexford

The nightmare of history is woven throughout “Aeolus,” Ulysses’ seventh episode. Journalists report historic events as they happen, playing an integral role in how events are viewed, past, present and future. However, no matter how memorable a battle may have been, it seems our newsmen in the Evening Telegraph office don’t remember it with much precision (at least editor Myles Crawford doesn’t). Upon Crawford’s entry to the scene, Professor MacHugh declares, “And here comes the sham squire himself!” Even if we don’t know quite what a “sham squire” is, we can tell that MacHugh is teasing the ruddy-faced editor, who fires back, “Getonouthat, you bloody old pedagogue!”

So then, who or what is a sham squire? And what has it got to do with Myles Crawford, journalism, Ulysses or anything for that matter?

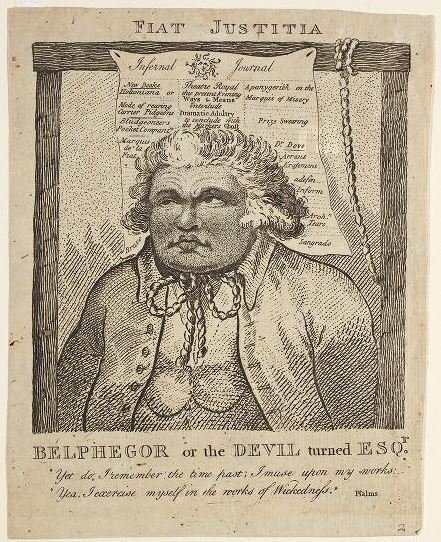

A caricature of Higgins from the early 19th c.

To answer these questions, we must look to 18th century Dublin and the life of one of Ireland’s most prolific grifters, Francis Higgins. Though he was born into poverty, Higgins’ influence would alter the course of Irish history before the end of the century. As a young man, he used his finely honed skills as a forger to weasel his way into high society. He cooked up papers showing that he was a gentleman in possession of an estate in County Down worth £3,000 per annum. Higgins’ work was so convincing that he persuaded a family of good reputation to allow him to marry their daughter. It was discovered soon after the nuptials that Higgins owned no estate whatsoever and was worth a whopping £0 per annum. Higgins served a few weeks in jail for his deceit, while his victims all died within the year. Far worse for Higgins, the judge who oversaw his case coined the nickname “Sham Squire,” a nickname that would plague him until the end of his days.

Higgins took up his various money-making schemes again following his release from prison. Though he was reputedly semi-literate, Higgins knew that commanding the written word won him even greater wealth, influence and entry into Dublin’s high society. Higgins used his connections to gain the editorship of the Freeman’s Journal. Prior to Higgins’ tenure as editor, the Freeman’s Journal was staunchly opposed to British rule in Ireland. Higgins put an end to that, currying the favor of the pro-British establishment by slanting the paper’s coverage in their favor. During this time he honed another lucrative skill set: sharing secrets with the government in Dublin Castle.

The 1780’s and 90’s were a tumultuous era in history, as the American colonies had recently fought and won a revolution against the British, and the French had overthrown their monarch in a bloody revolution. The Catholic population of Ireland had obtained some rights with the loosening of the Penal Laws, but they were still second-class citizens in their own country. Following these other revolutions, some factions of the Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland also saw opportunity in greater distance from the Crown. In this atmosphere, the non-sectarian United Irishmen formed. They hoped to build an alliance with France and overthrow British rule in Ireland.

The Arrest of Lord Edward Fitzgerald, Isaac Cruikshank, 1845

The United Irishmen succeeded in building a French invasion force, accompanied by United Irishman Theobald Wolfe Tone, but the fleet and their hopes were destroyed in a storm off the west coast of Ireland. The land-based United Irishman had planned to launch their own uprising in Dublin in 1798, but on the eve of their insurrection, their leadership was suddenly arrested. Lord Edward Fitzgerald, one of the most prominent leaders of the United Irishmen, escaped capture and went into hiding. A reward of £1,000 was offered to anyone who knew of Fitzgerald’s whereabouts. In the end, an informant revealed his location, and the authorities closed in. Fitzgerald tried to escape again, but died of wounds incurred during his arrest. He was interred at St. Werburgh’s Church in Dublin, which Leopold Bloom recalls in “Hades” for its famous organ that he imagines is played with corpse-gas.

The mystery of who informed on Sir Edward Fitzgerald endured until the mid-19th century. Around that time, an antiquarian bookseller acquired a bundle of documents from Dublin Castle. Tucked in the stacks of uninteresting, procedural documents was a ledger called “Secret Service Money Expenditure” containing the entry, “June 20th (1798) F.H. Discovery of L.E.F., £1,000.” “F.H.” must surely be Francis Higgins and “L.E.F.” Lord Edward Fitzgerald. The documents made clear that F.H. didn’t discover L.E.F.’s location on his own; he used his networks of spies that he had cultivated through the Freeman’s Journal to discover Fitzgerald’s hiding spot and then passed the information on to the authorities. If initials in a ledger aren’t strong enough proof for you, in another book, The Memoirs and Correspondence of Marquis Cornwallis, Higgins is also named as the informer who brought down the rebels:

“Francis Higgins, proprietor of the Freeman’s Journal, was the person who procured for me all the intelligence respecting Lord Edward Fitzgerald, and got £300 to set him, and has given me much information.”

Cornwallis was the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland in 1798. The Sham Squire received a pension of £300 a year for his efforts, and his name became synonymous with treachery all the way down until 1904.

Back to our boys in the newsroom.

MacHugh isn’t accusing Crawford of any high crimes or misdemeanors. This is just a bit of banter in which he calls Crawford the name of the most ignominious person to hold the position of editor in Freeman’s Journal history. However, like a pebble dropped in a pond, this comment ripples out over the next few headlined sections, turning up memories of 1798 that linger just beneath the surface of Dublin’s consciousness.

After MacHugh and Crawford’s exchange, Ned Lambert asks if the editor will join the men for a liquid lunch, to which Crawford replies:

“—North Cork militia! the editor cried, striding to the mantelpiece. We won every time! North Cork and Spanish officers!

—Where was that, Myles? Ned Lambert asked with a reflective glance at his toecaps.

—In Ohio! the editor shouted.

—So it was, begad, Ned Lambert agreed.”

Ned “yes and’s” Crawford through a very peculiar conversation. His final comment (“So it was, begad”) is a verbal pat on the head of the old editor, as Crawford’s response to the question, “Will you join us, Myles?” is bombastic, exuberant and totally nonsensical. Crawford turns out to be another Mr. Deasy figure - an older man very passionate about the history of his people while also being almost totally ignorant of its details, thankfully without the antisemitism this time.

The North Cork militia was real and they were active in 1798, however they were not quite as formidable as Crawford boasts. It’s possible that Crawford is revealing pride for his Cork roots. He is based on real-life Evening Telegraph editor Patrick Meade, who began his career in journalism on the Cork Herald. J.J. O’Molloy cautions Crawford in a later passage, “...your Cork legs are running away with you.” It’s possible that partisanship has clouded his memory, much like his Unionist counterpart Mr. Deasy.

The North Cork militia wasn’t made up of Corkmen, though. Like many territorial militias, their name was taken from where they were stationed. Loyal to the Crown, the North Cork militia took up arms against rebels in 1798. Prior to the summer of 1798, invasion was expected along Ireland’s west coast, similar to Wolfe Tone’s failed invasion. With the Eye of Sauron turned toward the rugged Atlantic Coast, the southeastern counties Wexford and Wicklow were left loosely garrisoned with British soldiers. During the summer, following the capture and death of Fitzgerald, the United Irishmen in the region saw their chance, taking up arms in revolt. Between 4,000 and 5,000 rebels, mainly armed with pikes, overwhelmed 110 men of the North Cork militia in battle on Oulart Hill in Wexford. The loyalist side was handily defeated, and the momentum of victory carried the United Irishmen forward, next winning a battle for control of the town of Enniscorthy.

Crawford is completely turned around, then - the North Cork militia actually lost a pivotal battle. Crawford’s claim that the North Cork militia went undefeated in Ohio is even more perplexing. Territorial militias didn’t serve outside of their home countries until the 1820’s, and even then they only served in Britain and Ireland. One guess about the Ohio outburst is that it could be related to the 1755 invasion of the French-held Ohio Valley by regiments that were once stationed in Cork. However, those regiments had only a very tenuous connection to Ireland and about half of their men were recruited in North America. Furthermore, the battle site is now part of Pennsylvania, not Ohio. If this is what Crawford is referring to, this section would be better titled “Obscure Battles Recalled.” Crawford’s real-life counterpart Patrick Meade’s brother James lived in Ohio and died there in the 1890’s. The reference to Spanish officers is a real head-scratcher as well, as both the North Cork militia and the regiments that fought in 1755 were commanded by British men.

It’s not clear why Crawford would make any of these connections or bring up any of these details in the context of “Aeolus.” Scholars have worked hard to connect these dots, but it’s hard for me to see any significance apart from mere dot-connecting. I think it’s not supposed to make sense, as this exchange fulfills a social function rather than an intellectual one. Crawford’s friends likely know he’s full of “shite and onions,” as Simon Dedalus would say. In a later section, Crawford also fudges the date of the Phoenix Park Murders, a major event that occurred during his journalistic tenure. Perhaps they enjoy winding him up because he doubles down when he’s said something ridiculous. Crawford’s absurd declamation could have just as easily been ignored, but notice Ned Lambert’s follow up, “Where was that, Myles?” You can imagine the other men mimicking Crawford’s, “Ohio!” once he’s out of earshot. Lambert whispers to J.J. O’Molloy, “Incipient jigs,” which is often taken to mean that Crawford has destroyed his mind with booze and that’s why he’s serving up word salad. If this is the case, the other men’s teasing is rather cruel. Crawford, for his part, chooses to express himself in song:

“—Ohio! the editor crowed in high treble from his uplifted scarlet face. My Ohio!

—A perfect cretic! the professor said. Long, short and long.”

The ever assiduous John Simpson at James Joyce Online Notes has tracked down a song from the early 20th century called “Ohio, My Ohio” which is set to the tune of “O, Tannenbaum.” This would indeed make the word “Ohio” a perfect cretic, a metrical foot in poetry with stress “long, short and long” as MacHugh notes. Despite his odd, disheveled character, he’s in on the jokes at Crawford’s expense.

In the next section, headlined O, HARP EOLIAN, MacHugh even accompanies the song. He pulls dental floss out of his pocket and “[twangs] it smartly between two and two of his resonant unwashed teeth.” On his ersatz harp, MacHugh plucks out “Bingbang, bangbang.” Whatever Crawford is up to, flossing your teeth in the middle of an office seems like the greater faux pas to me. This disgusting harp twangs amidst talk about battles fought for the freedom of the nation of Ireland, which is symbolized by the harp. If Crawford is a sham squire, MacHugh is a sham bard, turning the symbol of the nation into a bit of rubbish.

The men’s banter is interrupted by the horsplay of noisy newsies out in the hall. MacHugh scolds a straggler, but after the fray, they can be heard singing the song, “The Boys of Wexford,” which also dates to 1798. The lines included in “Aeolus” are the first half of the chorus. The chorus in full is:

“We are the boys of Wexford,

Who fought with heart and hand

To burst in twain the galling chain

And free our native land.”

“The Boys of Wexford” tells of victory for the rebels at Oulart, but also of the rebels’ last stand at Vinegar Hill where they were ultimately defeated. In some versions of the song, that final stanza goes:

“My curse upon all drinking it made our hearts full sore

for bravery won each battle but drink lost evermore

and if for want of leaders we lost at Vinegar Hill

we're ready for another fight and love our country still”

The version of the song embedded here is by John McCormack, with whom Joyce shared the stage in 1904. I think this would be the version of the song known to the characters of Ulysses. I listened to half a dozen or so versions of “The Boys of Wexford” in preparation for writing this post, and most of the later versions, such as The Wolfe Tones’ version from the mid-1960’s, alter that final stanza, removing those first two lines about how drink upended the rebels’ efforts despite their bravery and patriotism, changing it to:

“And Oulart's name shall be their shame,

Whose steel we ne'er did fear.

For every man could do his part

Like Forth and Shelmalier!

And if for want of leaders,

We lost at Vinegar Hill,

We're ready for another fight,

And love our country still!”

I think those lines about drink spoiling the grand plans of Irish men are meant as a warning to the men in the Evening Telegraph office. As we’ve detailed in other blog posts, alcohol has been the downfall of most of the men in the office (with the exception of Mr. Bloom). Even young Stephen, who once planned to “forge in the smithy of [his] soul the uncreated conscience of [his] race,” is presently squandering his salary on a round of drinks with the newsmen. The stagnation of Irish culture is a theme throughout Ulysses, and alcohol is usually the culprit. Alcohol is the cause of Crawford’s “incipient jigs” that make him think the North Cork militia must have won at Oulart Hill. The glory of memorable battles is recalled but not the substance. Someone won something and it was great, and therefore by extension we are great.

The image of these men hanging out, shirking their duties, and sneaking out for a midday pint stands in contrast to the two patriotic visions of Ireland laid out so far in this episode - the awe-inspiring grandeur of Ireland’s natural beauty in Dan Dawson’s overwrought speech and the heroic, if tragic, rebels fighting for freedom in “The Boys of Wexford.” Zach Bowen in his book Musical Allusions in the Works of James Joyce, points out that:

“The saviors of Ireland, the gentlemen of the press, are losing their battle for old Erin just as the boys of Wexford did, and for some of the same reasons!”

Bowen goes on to cast a similar judgment on the newsboys outside the office, stating:

“the boys that sing [the songs] today will be tomorrow’s frequenters of the Dublin bars.”

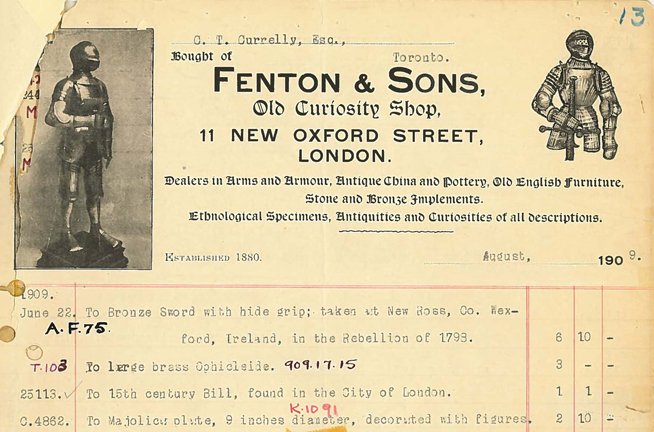

Let’s end on an odd little coda in which a memorable battle is recalled. In 1909, a shipment of antiquities arrived in Canada from Fenton & Sons Old Curiosity Shop in London. The first item on the manifest was listed as “Bronze Sword with hide grip; taken at New Ross, Co. Wexford, Ireland, in the Rebellion of 1798.”

Certifiably curious, the sword in time made its way to the Royal Ottawa Museum, where it was examined by archaeologist Francis Pryor in the 1980’s. If you’re a fan of the long running Channel 4 archaeology series Time Team, you’ll remember Pryor as the sometimes ostentatious Bronze Age expert from the earlier seasons. Pryor examined the sword and determined the only part of it not original was the hide grip and that it showed signs of recent use (at least more recent than the Bronze Age). Pryor found it credible that the roughly 3-4,000 year old sword could have been carried into battle in New Ross in 1798. To put it into perspective, the sword is possibly around the same age as Homer’s Odyssey. Similar swords tend to be found submerged in bogs, where the anaerobic conditions preserve the swords over the millenia. Conceivably, the sword was found while cutting turf and taken home. When the countryside rose in rebellion, the sword’s 18th century owner decided to put it to use, marching to battle at New Ross beside his friends and neighbors who were armed with pikes. We’ll never know for sure, but I can’t shake the vision of a young man brandishing a Bronze Age sword in the heat of battle one last time in 1798.

Further Reading:

Adams, R. M. (1962). Surface and Symbol: The Consistency of James Joyce’s Ulysses. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bowen, Z. (1974). Musical allusions in the works of James Joyce: Early poetry through Ulysses. Albany: State University of New York Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/y9erlwtw

Dorney, J. (2017, Oct 28). The 1798 rebellion -A brief overview. The Irish Story. Retrieved from https://www.theirishstory.com/2017/10/28/the-1798-rebellion-a-brief-overview/#.YcokNi-B1WM

Fishback, P. (2021). The British Army in Ulysses: Volume II of the British Army on Bloomsday. Birmingham, Alabama: F.F. Simulations, Inc. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/2t8rjmsv

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/vy6j4tk

Kee, R. (2003). Ireland: a history. London: Abacus.

Looby, D. (2018, Feb 03). Ancient sword shines in Ottawa museum. The Irish Independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.ie/regionals/goreyguardian/news/ancient-sword-shines-in-ottawa-museum-36544180.html

Lysaght, M. (1972). The Sham Squire. Dublin Historical Record, 25(2), 64–74. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30104376

Mason, R. (2013, Dec 18). Weapon Wednesday: The Long History of an Irish Bronze Age Sword. Royal Ottawa Museum blog. Retrieved from https://www.rom.on.ca/en/blog/weapon-wednesday-the-long-history-of-an-irish-bronze-age-sword

O’Cathaoir, B. (2004, Oct 11). An Irishman’s Diary. The Irish Times. Retrieved from https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/an-irishman-s-diary-1.1161407

Simpson, J. A perfect cretic floating down the O-hi-O. James Joyce Online Notes. Retrieved from https://www.jjon.org/joyce-s-allusions/ohio-1

Image Source for Sham Squire caricature: https://www.ecis.ie/francis-higgins/