Is Leopold Bloom Phoenician?

“[The Irish language] is oriental in origin, and has been identified by many philologists with the ancient language of the Phoenicians, the originators of trade and navigation, according to historians. This adventurous people, who had a monopoly of the sea, established in Ireland a civilization that had decayed and almost disappeared before the first Greek historian took his pen in hand.” - James Joyce in “Ireland, Island of Saints and Sages,” 1907

**Author’s Note**

This topic started out as a single post but has ballooned to require the space of two posts to fully support its weight. This is part two of two, and while you don’t need to have read Part 1 to read this, I recommend it anyway! In Part 1, we explore Orientalist motifs in the episodes “Calypso” and “Lotus Eaters”. Part II focuses on Irish Orientalism as a concept and how it influenced James Joyce’s worldview prior to writing Ulysses.

To listen to a discussion of this topic, check out the podcast version here.

We talked a lot in Part 1 about how the Orientalist motifs in Ulysses are a product of British colonialism. Ireland’s position in the tangled web of identity and colonialism of the period in which Ulysses takes place is incredibly complex and worthy of exploration on its own terms. To focus on Ireland’s relationship to Orientalism, we must first gain an understanding of Ireland’s unusual niche in the British Empire. After the Act of Union in 1801, Ireland was considered part of the United Kingdom. Dublin was a secondary city within the UK, and Ireland itself was seen by some as “West Britain” due to factors like geographic proximity, a shared language, and skin-color. In this view, Ireland’s similarity to Britain, some aspects of which were imposed upon them by the ruling British, meant that the Union was inevitable.

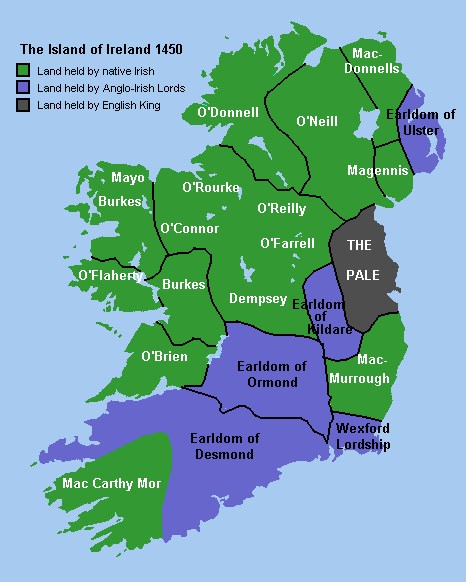

The Irish middle- and upper-classes benefited from the spoils of imperialism in ways that citizens of other colonies didn’t. Historically, Dublin was at the center of a region called the Pale. As the nucleus of English rule in Ireland, the Pale contrasted itself with the domain of the indigenous Gaelic Irish outside its border. Have you ever heard something described as “beyond the Pale” to mean it’s sort of shocking, uncivilized or uncouth? This arrangement is the origin of that expression.

The anglicized people living within the Pale considered themselves several steps above the folks outside it. To use an example from Ulysses, someone like Buck Mulligan would have more in common with an English person of similar class stature than with a tenant farmer in the West of Ireland. This class tension is part of what makes his presence so grating to Stephen. Mulligan is happy to accommodate Haines’ quirks while relentlessly mocking Stephen, his own countryman. Symbolically, we see that an Irish artist is only fit for mockery in the eyes of the Ascendancy while an Oxford-educated English hack is seen as a superior (or at least worth touching for a guinea here and there).

The influence of British rule over Ireland also influenced Ireland’s relationship to the areas of the world considered “The Orient.” As we saw in Part 1, the characters in Ulysses are often fascinated by their idea of what the Orient must be like. Their imaginations are informed by culture both high and low rather than direct experience. Because of this, their opinions and fantasies are often filtered through the lens of imperial Britain. Leopold Bloom, a lifelong Dubliner, is often characterized as foreign and “Oriental” by those around him because of his Hungarian Jewish heritage. Though he is labeled Oriental, he doesn’t have a very sophisticated view of what the Orient is actually like, as we see in his reveries in “Calypso” and “Lotus Eaters.”

Focusing on his experience in the latter episode, window shopping at the Belfast and Oriental Tea Company pulls Bloom into a daydream about what life might be in Ceylon, imagining:

“those Cinghalese lobbing around in the sun, in dolce far niente. Not doing a hand’s turn all day. Sleep six months out of twelve.”

I have no experience farming tea myself, but I imagine that you probably can’t get away with sleeping half the year when the Belfast and Oriental Tea Company is nipping at your heels. Bloom’s Far East fantasy is built entirely on the stereotype of the colonial subjects of South Asia being far less industrious than their British masters. It comes easily to his mind, so it seems to be a bias he’s absorbed from the culture around him.

Later in “Lotus Eaters,” Blooms ponders religion while observing Mass and thinks about Christian missionaries to China,

“Wonder how they explain it to the heathen Chinee. Prefer an ounce of opium…. Buddha their god lying on his side in the museum. Taking it easy with a hand under his cheek.”

This passage contains lots of references to the colonial worldview. Christian missionary work, the act of converting the “heathens” to Christianity, imposes the colonizer’s moral and cultural system on their colonial subjects. Bloom’s association of China with opium is likely a reference to Opium Wars of the 19th century. Association of a foreign people with vices like drugs is part of this colonial mindset. I won’t get into Bloom’s total misunderstanding of Buddhism (that’s for another post), but the Buddha statue on display in the National Museum of Ireland is definitely imperial contraband. According to Fintan O’Toole, writing in the Irish Times, “Col Sir Charles Fitzgerald, an Irishman in the British army in India, stole it while on a punitive military expedition to Burma in 1885-6. In 1891, Fitzgerald sent it, along with other looted Burmese statues, to the museum.” Clearly Ireland was embiggened at least culinarily and culturally by imperial commerce and plunder. Furthermore, though Bloom has lived his life in Ireland and doesn’t seem to be loyal to the Crown, he has unconsciously absorbed many misconceptions and biases about the East. Does this make him and his peers the victims of colonial rule or beneficiary citizens of the United Kingdom, profiting from imperial plunder?

It’s complicated.

Because the Irish culture of Joyce’s era was so steeped in British influence, it could be hard to tell where one ended and the other began. Some believed that the Irish were uncivilized barbarians until the English arrived on their shores and whipped them into shape. It followed then that Irish peasants were poor because they were Irish, possessing some inherently indigent quality that resulted in their lowly status. Think of Mr. Deasy’s insistence that the pride of the English was that they could pay their way and never incurred debts. This belief paints the English as inherently middle class - always possessed of the money they need to live. The flip side is that Irish people are inherently poor and don’t value economics and prosperity in the same way as the English. This in turn lets the ruling classes off the hook for maintaining an unequal society. There’s no need to reform a society if the people living in it are incapable of “bettering” themselves; their poor state is simply God’s will.

The liminal status of middle- and upper-class Irish people complicated their view of their own position in UK society. On one hand, Unionists like Mr. Deasy were happy to live under British rule and took pride in their status. On the other hand, the Protestant Ascendancy also produced its fair share of revolutionaries, such as Maud Gonne and Sadhbh Trench who we’ve discussed previously. Writers like William Butler Yeats and Lady Gregory counteracted the assumption of British Supremacy through the Celtic Revival movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Revivalists writers aimed to depict a Gaelic Ireland devoid of English influence by centering the Irish language and Irish myths. Many drew inspiration from interacting with Irish people native to the West of Ireland in regions like Connemara and the Aran Islands.

Illustration from The Boys’ Cuchulain, 1904

Interestingly, this movement, fostered by members of the upper classes, followed patterns reminiscent of Orientalism. Works that came out of this movement tended to focus on highly idealized representations of Irish identity, crafting an image of Ireland as a magical land populated by gods, mythical creatures, and otherworldly women. Others depicted pious, innocent peasants living in harmony with the land, upholding nearly-forgotten traditions. This fantastical Ireland stood as a counterpoint to modernity, offering a spiritual alternative to the rational progress of British Imperialism. It in no way reflected the lived experience of the people who made their homes in rural Ireland, particularly in the West. It instead reflected an idealized idea of Ireland that appealed to wealthy Anglo-Irish people. Just as traditional stories from the Middle East were retooled to appeal to Europeans in works like A Thousand and One Nights, Irish folklore was translated to reflect the values of the era. A once-lusty hero like Cúchulainn suddenly becomes quite chaste when constrained by Victorian mores. Much like Orientalist stereotypes, this mythical stereotype of Ireland survives into the 21st century.

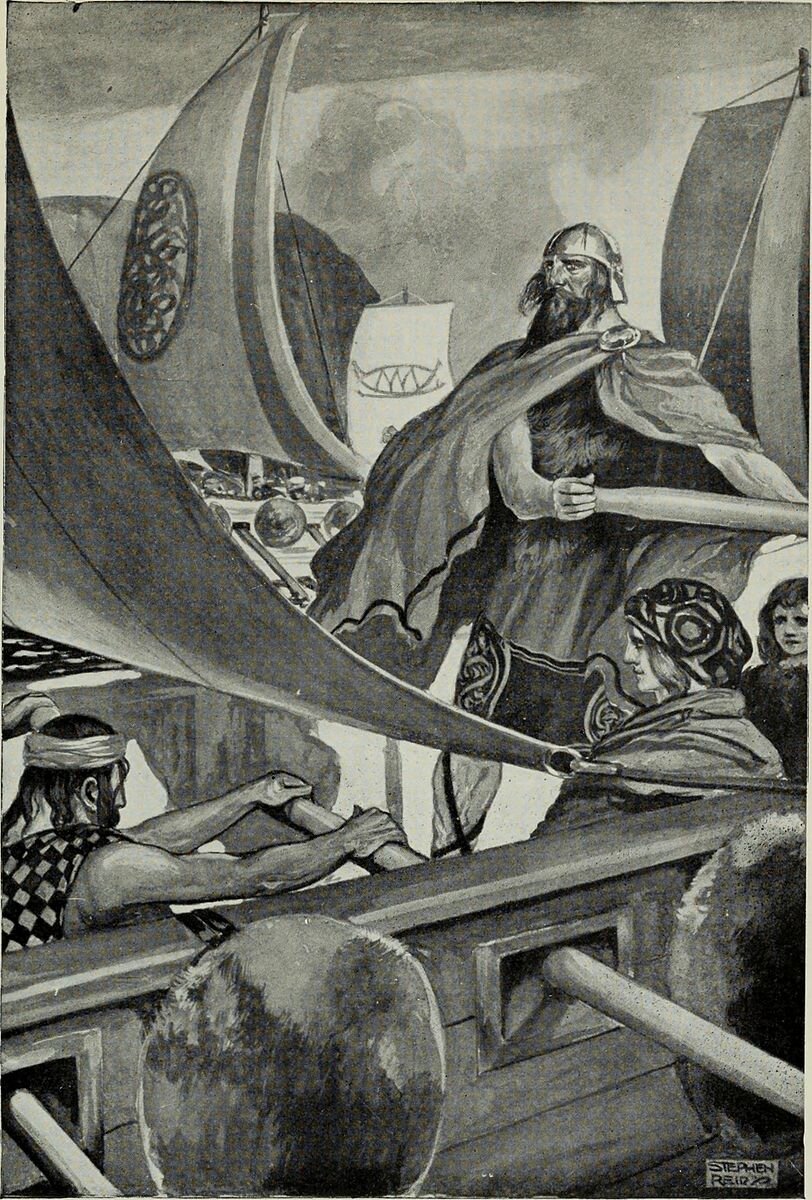

"The Coming of the Sons of Miled," c. 1911

While the Revivalists looked to Ireland’s “past,”others looked further afield - to the Orient. The belief that the Irish people’s origins lie in the Orient date back to The Book of Invasions, a medieval manuscript that tells Ireland’s origin story. Sort of. It’s a mix of pagan and Christian mythology, but aspects of its tales were taken as fact into the era in which Ulysses was written. The Book of Invasions tells of a succession of monsters and gods who deposed one another until a group called the Milesians showed up and took the wheel. The mythological equivalent to the historical Gaels, the Milesians are the forebears of the people today we call “Irish.” In mythology, the Milesians (Gaels) were said to have descended from Noah’s son Japhet in the Near East. The Milesians spent time in Scythia and Egypt before setting sail through the Mediterranean and then heading for Ireland via Iberia (the peninsula that is home to modern-day Spain and Portugal). The Milesians take their name from Milesius, whose latinized name is derived from the phrase “Miles Hispaniae,” or “Soldier of Hispania.”

What’s not clear to me is if this story predates Christianity in Ireland or not. The Book of Invasions was written in a Christian Ireland. There is recent DNA evidence that indicates that Neolithic inhabitants of Ireland (such as the people who built Newgrange) were likely dark-skinned people from the Near East who were genetically distinct from the Mesolithic people they displaced. However, the Gaels are believed to have arrived during the Bronze Age, displacing the Neolithic people. Due to my limited knowledge of The Book of Invasions, it’s unclear to me whether this story of invasions is some long held myth based in history or an attempt to give the Irish a direct connection to Biblical patriarchs or both.

Let’s flash forward to the 17th century and meet Roderic O’Flaherty, who wrote in a book called Ogygia in which he posited that the Irish people originated in Phoenicia and migrated over the sea to Ireland. You might recognize the name Ogygia as Calypso’s island in The Odyssey where Odysseus was marooned for 20+ years. O’Flaherty believed that Homer, who was believed by some to be Phoenician in origin, was referring to Ireland when he wrote about Odysseus trapped on Ogygia. O’Flaherty borrowed heavily from myths similar to those found in The Book of Invasions to get the ancient Phoenicians to Ireland.

O’Flaherty’s Phoenician hypothesis had traction, and held on into the 20th century. As late as 1922, a book published by the Oxford University Press explained that Ireland was first settled by the Phoenicians and that the ruins of Dun Aengus were built by them as well. In the 18th century, Charles Vallancey wrote a detailed linguistic analysis of the Irish language, tying it to the Semitic language spoken by the ancient Phoenicians. The poet Thomas Moore believed that the Irish were actually descended from the ancient Persians and attempted to draw a parallel between the Zoroastrian fire temples of antiquity and the round towers found in early Christian sites in Ireland, though he seems to be alone in that assertion. Linking the Irish to the Phoenicians seems to be particularly key since the Phoenicians held colonies throughout the Mediterranean, such as Carthage in modern day Tunisia, and in Iberia, following the path of the Milesians in The Book of Invasions.

This set of beliefs is sometimes termed Irish Orientalism - the imagining of the Orient as the mythical Eden whence the Irish sprung. The historical Gaels don’t seem to have any connection to Semitic peoples in the Near East, and I think it’s fair to say Milesius only existed in the realm of myth. As a result, it’s easy to toss these theories out as silly or fantastical, but they do give us a window into the minds and worldview of Irish thinkers of an earlier era. Getting into such a mindset is invaluable to understanding the world in which Ulysses takes place and the world in which James Joyce lived and wrote Ulysses. It also allows us a moment to contemplate just how recently our DNA-informed notion of the world and the origins of its peoples came into being. It’s quite astonishing when you think about it.

Newgrange

The belief that the Irish are descendents of the Phoenicians or another Near Eastern group allows the Irish people a hidden past steeped in nobility and grandeur. It’s sort of like realizing, as a culture, that you’re actually a wizard rather than a sad kid living under a staircase. Ireland occupied quite a lowly position in the British Empire - Dublin was one of the poorest cities in Europe at the turn of the last century. As Joseph Lennon put it in his book Irish Orientalism, Ireland’s purported connection to the Orient symbolizes immutability, antiquity and perpetuity. A connection with an ancient lineage such as Phoenicia was proof that the Irish were embarrassed kings rather than barbarians or West Britons and one day would be again.

Additionally, an ancient lineage divorced from English rule meant that the Irish were perfectly capable of ruling themselves and didn’t require their colonial rulers to civilize them, a notion having real-world political implications leading up to 1916. Their civilization pre-dated Britain’s by centuries! This detail is particularly key to understanding the appeal of Irish Orientalism. The influence of the English on Ireland was so dominant, as English culture had been forced on the Irish - their language, their religion to a certain extent - proving that the destiny of the Irish was naturally connected to English rule. The idea of an independent Ireland in this scenario was absurd on its face since the two were so historically intertwined. Why would Ireland become independent when there was so much evidence that it was truly just West Britain? An origin outside the context of British colonialism was a powerful rebuttal to this argument.

It's worth noting that the interest in Irish Orientalism was mainly a hobby of the middle- and upper-classes, much like Celtic Revivalist literature. They had a sense that the wealthy classes in England were getting a bigger proportion of the colonial spoils than they were, and the wealthy in Ireland wanted their fair share, as they felt they were on par socially with their English peers. Revivalist literature didn’t imagine an Ireland for everyone. Rather, it portrayed an Ireland that was the birthright of an Irish nobility. It upheld the same rigid class structure that existed in English society, just more… Irish. Orientalism in any form is a tool of nationalism and can be manipulated to justify exploitation on the part of the wealthy. Irish Orientalism could be used in a similar way - pointing out an ancient, noble lineage to argue that the wealthy Irish were just as entitled to imperialist largesse as the English.

This brings us finally to James Joyce. Like many European men of his time, Joyce was fascinated by the notion of the Orient. As a young man, his personal familiarity was mainly funneled through popular works like A Thousand and One Nights, and through Anglo-Irish spiritualists like Yeats and Æ Russell. When Joyce settled in Trieste, at that time part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, he experienced life in a diverse city at the crossroads of East and West where he made friends quite different from his friends from home, including Jewish friends like Ettore Schmitz who so inspired him. Though Trieste may not sound particularly exotic by 21st century standards, for a young Dubliner in the early 1900’s it was Oriental enough. Joyce had a complicated view of Orientalist studies, as on one hand, he was fascinated with the languages and cultures of the East, but on the other hand, he also felt that students of these topics were furthering the cause of the Imperialist British government.

In 1907, Joyce gave a lecture entitled “Ireland, Island of Saints and Sages,” in which he promulgated the Phoencian hypothesis to an Italian audience. Thus spake Joyce:

“[The Irish] language is oriental in origin, and has been identified by many philologists with the ancient language of the Phoenicians, the originators of trade and navigation, according to historians. This adventurous people, who had a monopoly of the sea, established in Ireland a civilization that had decayed and almost disappeared before the first Greek historian took his pen in hand. It jealously preserved the secrets of its knowledge, and the first mention of the island of Ireland in foreign literature is found in a Greek poem of the fifth century before Christ, where the historian repeats the Phoenician tradition. The language that the Latin writer of comedy, Plautus, put in the mouth of Phoenicians in his comedy Poenulus is almost the same language that the Irish peasants speak today, according to, the critic Vallancey.”

Ireland’s reputation as the land of Saints and Sages (or Saints and Scholars) was tied to the early Irish Christian tradition of sending its leading holy men to Europe to spread the Faith. In “Proteus,” Stephen mockingly likens himself, a most unsaintly young man, to early Christian saints like Columbanus and Fiachra who were canonized for their efforts on the Continent. Using Vallancey’s linguistic analysis as a basis, Joyce argued that the “Sages” referenced were actually the wise men of ancient Phoenicia, while the “Saints” were priests of ancient Egypt who traveled to Ireland in antiquity and became the Druids.

Phoenician Merchants and Traders, 1880’s

Joyce’s embrace of the Phoenician hypothesis is particularly fascinating since he uses it to not only decouple Ireland’s history from Britain, but also from the supremacy of the Catholic Church. Ireland was populated by wise men and holy men thousands of years before Patrick ever so much as imagined a shamrock. This ancient wisdom existed in Ireland from time immemorial and was the birthright of its people, separate from the Church. Ireland’s successful monastics, then, did not arise as a result of Christian enlightenment, but because of their ancient Oriental roots.

An Irish-Phoenician connection adds a layer of understanding to Joyce’s characterization of Leopold Bloom. Joyce was fond of Victor Bérard’s analysis of The Odyssey in which Bérard asserted that Odysseus was himself a Phoenician. An Irish Everyman must be Phoenician in his distant ancestry. Bloom represents this heritage, as he is both Irish and Semitic. Dublin itself takes on a similar hybrid quality in Ulysses as it transforms through metempsychosis into the ancient Mediterranean as Bloom-Odysseus voyages throughout.

Joyce’s embrace of the Phoenician hypothesis set him apart from the Celtic Revivalists in one more key way - it allowed him to imagine an Ireland with diverse inhabitants. A current of racial purity underlies the mythic Ireland of Revivalist literature, which conjures a “true” Irish culture unadulterated by foreigners. Descent from ancient Phoenicians eliminates the possibility of a racially pure Ireland. Joyce, in drawing parallels between Ireland and the Orient, was able, in his mind, to reject “the old pap of racial hatred.” Joyce certainly plays into racial and ethnic stereotypes in Ulysses, but he also envisions a modern Ireland that has room for people like Leopold and Molly who are undeniably Irish, but also just foreign enough for their Irishness to be questioned or qualified by their peers, even by one another.

Joyce wanted to see Ireland modernize, or more to the point, to become more forward-thinking like Continental Europe. A key component to nurturing a worldy Ireland is to embrace the nation’s diversity. Consider the Citizen’s rejection of Bloom as Irish. The Citizen represents an insular view of the Irish people. It’s no mistake that the narrative of “Cyclops” is interspersed with spoofs of those old Irish myths so beloved by the Revivalists. Their ideas belong to a long dead past, not to the lived reality of actual Dubliners. In her essay “Phoenician Genealogies and Oriental Geographies: Joyce, Language and Race”, Elizabeth Butler Cullingford wrote, “Leopold Bloom, a peripatetic Jew whose ethnic identity is uncertain,... who fantasizes about the Orient, and who is subjected to the racial hatred of Irish nationalists, embodies… Joyce’s affirmation of cultural hybridity through the myth of Wandering Ulysses, the Semitic Phoenician.” Through Bloom, we find the means to build a new Bloomusalem - a modern Ireland with room for all people.

Further Reading:

Bongiovanni, L. (2007). “Turbaned Faces Go By”: James Joyce and Irish Orientalism. Ariel: A Review of International English Literature, (38) 4 (2007): Retrieved from https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/ariel/article/view/31180

Butler Cullingford, E. (2000). Phoenician genealogies and oriental geographies: Joyce, language and race. In D. Attridge & M. Howes (eds.), Semicolonial Joyce (219-239). Cambridge University Press.

Herring, P. (1974). Lotuseaters. In C. Hart & D. Hayman (eds.), James Joyce’s Ulysses: Critical essays (71-90). Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/wu2y7mg

Ito, E. (2008). Orienting Orientalism in Ulysses. James Joyce Journal, 41(2), 51-70. Retrieved from http://p-www.iwate-pu.ac.jp/~acro-ito/Joycean_Essays/U_Orientalism.html

Joyce, J. (1907). Ireland, Island of Saints and Sages. Retrieved from http://www.ricorso.net/rx/library/authors/classic/Joyce_J/Criticism/Saints_S.htm

Kershner, R. (1998). "Ulysses" and the Orient. James Joyce Quarterly, 35(2/3), 273-296. Retrieved July 14, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/25473906

Lennon, J. (2008). Irish Orientalism. Syracuse University Press. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/books/edition/Irish_Orientalism/nnbRKOsmyJIC?hl=en&gbpv=0

McKenna, B. (2002). James Joyce’s Ulysses: A Reference Guide. Greenwood Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/y2oth7lc

Said, E. (1978). Orientalism. Vintage Books.

Shloss, C. (1998). Joyce in the Context of Irish Orientalism. James Joyce Quarterly, 35(2/3), 264-271. Retrieved July 14, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/25473905