Ground Control to Major Tweedy

“Hard as nails at a bargain, old Tweedy. Yes, sir. At Plevna that was. I rose from the ranks, sir, and I'm proud of it. Still he had brains enough to make that corner in stamps. Now that was farseeing.” - Leopold Bloom, p. 56

To listen to a discussion of this topic, check out the podcast episode here.

Early in “Lotus Eaters”, Bloom ducks into the Westland Row post office under the guise of Henry Flower. He glances at the military recruiting posters tacked up inside:

“He slipped card and letter into his sidepocket, reviewing again the soldiers on parade. Where's old Tweedy's regiment?“

“Old Tweedy” is Major Brian Cooper Tweedy, father of Marion, father-in-law of Leopold. He first got a shout-out in “Calypso” as Bloom was thinking about Molly lying half-asleep in their jingly bed:

“Wonder what her father gave for it. Old style. Ah yes! of course. Bought it at the governor's auction. Got a short knock. Hard as nails at a bargain, old Tweedy. Yes, sir. At Plevna that was. I rose from the ranks, sir, and I'm proud of it. Still he had brains enough to make that corner in stamps. Now that was farseeing.”

In the same episode, Old Tweedy also appears in Bloom’s orientalist fantasy:

Walk along a strand, strange land, come to a city gate, sentry there, old ranker too, old Tweedy's big moustaches, leaning on a long kind of a spear.

Major Tweedy appears in Bloom’s thoughts somewhat frequently, though he never appears as a character on-screen in the novel. I think it’s fair to infer that Bloom had a good relationship with his father-in-law, who exuded a certain amount of bold masculinity in Bloom’s memory. He was impressively mustachioed, perhaps looking a bit like Turko the Terrible (in my imagination, he looked a bit like Lord Kitchener). The first time he’s mentioned in the novel, we learn he’s “hard as nails at a bargain” and that he won the Blooms’ jangly, old bed at a governor’s auction in Gibraltar where he “got a short knock” - meaning that the auction ended quickly, ensuring the buyer a lower price. This alludes to some chicanery on the Major’s part since, as Bloom acknowledges in the next paragraph, “lots of officers are in the swim.” I think Bloom privately finds this little bit of dishonesty kind of cool - a bit edgy and daring on the Major’s part, perhaps proof of his prowess for bargaining or of his friends in high places.

In addition to being cozy with auctioneers, we learn that Tweedy was also a keen philatelist, or stamp enthusiast. Bloom admires the Major’s brains “to make that corner in stamps,” meaning that the Major bought up a run of postage stamps that ended up being valuable. Was he in the swim here, too? Again, Bloom doesn’t exactly chastise his father-in-law if he was. In any case, the Major’s keen eye for “stickyback pictures” has clearly left an impression on Bloom, as he imagines finding rare postage stamps as a “rapid but insecure means to opulence” in “Ithaca.”

No matter what unsavory business he got up to at auctions and stamp-collecting, Tweedy earned his rank of officer. He wasn’t some spoiled kid born with a golden spoon in his mouth like the boys at Deasy’s school. No, Tweedy rose from the ranks of ordinary soldiers, distinguishing himself at the siege of Plevna during the Russo-Turkish War and earning his position as an officer in the imperial army. Bloom remarks on this twice in these early episodes: recalling the Major saying, “I rose from the ranks, sir, and I'm proud of it” and referring to him as an “old ranker” in the daydream. Perhaps Bloom is inspired by this self-made man.

Leopold isn’t the only Bloom to reminisce about the old Major, though. Molly thinks of him during her soliloquy in “Penelope” and clears up, for us readers anyway, some of her husband’s misconceptions about her father. First, the matter of the Blooms’ bed. Leopold is correct in thinking it came from Gibraltar, but a governor likely never slept in it. Thus spake Molly:

“...the lumpy old jingly bed always reminds me of old Cohen I suppose he scratched himself in it often enough and he [Bloom] thinks father bought it from Lord Napier [governor of Gibraltar]...”

She refers to the bed one further time as “old Cohen’s bed” before the end. It’s not clear who old Cohen was, but he almost certainly wasn’t a governor. It seems the old Major may have pulled Leopold’s leg here and that Molly never corrected the record. It’s also not clear why, apart from holding the secrets of their marital bed parallels Molly symbolically with Penelope in The Odyssey. My personal theory is that she knew Leopold admired her father, and she didn’t have the heart to correct her husband by telling him that it was Old Cohen who’d scratched himself in the bed rather than Lord Napier. As for the Major’s philatelic treasure, Molly thinks:

“... my accent… all that father left me in spite of his stamps…”

Molly seems to confirm here that the Major made some money trading in valuable stamps, but that by the time he passed, the only thing she inherited from him was an accent that marked her as lower class.

Molly’s memories of the Major’s military accomplishments vary quite a bit from Leopold’s, as well. Just before she remembers her father’s passing, she thinks about social-climbing women, “...sparrowfarts skitting around talking about politics they know as much about as my backside….” Molly identifies herself in this section as “soldiers daughter am I” and imagines how shocked these women would be seeing her on an officer’s arm. Molly is conscious of her lowly class status, unusual for the daughter of a major, though clearly she describes herself as a “soldiers daughter” rather than a major’s daughter or officer’s daughter. If she were an officer’s daughter, it would be natural for her to step out with men from the officer class. Also, wouldn’t her father have more to leave her than old postage stamps? Plevna, the battle that led to her father’s proudest achievement, is mentioned only once in “Penelope”:

“Captain Groves and father talking about Rorkes drift and Plevna and sir Garnet Wolseley and Gordon at Khartoum…”

Let’s untangle these names. Wolseley and Gordon are connected to the Siege of Khartoum in Sudan, where Mahdist forces held a ten-month siege of the city. Wolseley was sent to relieve the British garrison, headed by Gordon. They were too late, though, and Gordon and most of his men were killed. Rorke’s Drift refers to a small, British-held post in South Africa that was attacked by a Zulu contingent. Though hospital patients outnumbered soldiers at the post, they were able to successfully defend their position. All officers present were promoted to the rank of major. During the Siege of Plevna, which took place during the Russo-Turkish War, the Ottoman Turks were able to hold back the Russian Army for five months before capitulating in the end.

Capturing Grivitza, Henryk Dembitzky, 1881; this painting shows a major turning point in the Siege of Plevna

This is where things get hairy. Major Tweedy also makes an appearance in “Circe.” Bloom says of his wife and father-in-law:

“My wife, I am a daughter of a most distinguished commander, a gallant upstanding gentleman, who do you call him, Majorgeneral Brian Tweedy, one of Britain’s fighting men who helped to win our battles. Got his majority for the heroic defence of Rorke’s Drift.”

Bloom has changed the details - from Plevna to Rorke’s Drift. Interesting. Also, Old Tweedy is now a “majorgeneral.” Double interesting. Though, Bloom is on trial in this scene, so perhaps the extremity of the situation caused him to exaggerate. Towards the end of “Circe,” when Stephen gets into an altercation with Privates Carr and Compton, Major Tweedy, “mustachioed like Turko the Terrible” enters the fray with the battle cry, “Rorke’s Drift! Up, guards, and at them!” Again, Rorke’s Drift is front and center. Maybe it’s possible Bloom just misremembered the name of the battle back in “Calypso,” conflating two tales of heroism from the Major’s storied career. Bloom’s memory has proven faulty more than once, after all.

We learn in “Ithaca” that Bloom has a copy of Hozier's History of the Russo-Turkish War, bearing a “gummed label, Garrison Library, Governor's Parade, Gibraltar, on verso of cover.” The label makes it seem like Bloom either borrowed or was gifted this book from the Major, who in turn must have permanently “borrowed” it from the garrison library in Gibraltar. Bloom goes on to connect Tweedy and Plevna through “mnemotechnic,” or a mnemonic device:

“What among other data did the second volume of the work in question contain?

The name of a decisive battle (forgotten), frequently remembered by a decisive officer, major Brian Cooper Tweedy (remembered).

Why, firstly and secondly, did he not consult the work in question?

Firstly, in order to exercise mnemotechnic: secondly, because after an interval of amnesia, when seated at the central table, about to consult the work in question, he remembered by mnemotechnic the name of the military engagement, Plevna.”

However, if Bloom had consulted the Hozier volume rather than relying on his quirky memory, he’d have learned that the British army never fought at Plevna, and so it would be very unlikely that Major Tweedy would have been present at the battle, much less earned an officer’s rank for service there.

Returning to Rorke’s Drift, where Bloom claims Tweedy earned his majority, the officers present were promoted to major, but Tweedy said that he rose from the ranks, remember. He wouldn’t have been an officer but rather a soldier (making Molly a soldier’s daughter), and thus wouldn’t have been promoted to major. Despite Tweedy’s claims of meritocracy, rank in the British army of the period was heavily class-biased, with officer positions reserved for members of prominent families. Tweedy could rise through the ranks for stellar service, but it would be nearly impossible to rise from them.

When you start to construct a rough timeline, more and more about the Major’s biography doesn’t add up. Molly was born in early September 1870, and her mother was from the area, so Tweedy was present in Gibraltar at that time.One of Molly’s earliest recollections in “Penelope” was hearing the “damn guns bursting and booming all over... when general Ulysses Grant whoever he was or did supposed to be some great fellow landed off the ship” in Gibraltar. Grant visited in late 1878 when Molly was 8, so she would have been living in Gibraltar while her father was off on his exploits - Plevna was in 1878 (thought probably without Tweedy) and Rorke’s Drift was in January of 1879 (just on the heels of Grant’s visit).

Ruth von Phul deduced that Molly’s memories become clearer around the time she turned 10 (1880) and that this seems to be connected to better living conditions for the Tweedys at that time. Molly likely lived a lonely childhood as her father was away fighting for the Empire and she didn’t know her mother, “whoever she was.” She must have been in the care of a third party. Von Phul believes that Molly’s clearer memories are connected to her father earning more money and living full-time in Gibraltar with her. This timeline seems to work if he was promoted after Rorke’s Drift in 1879.

But wait, there’s more.

The Defence of Rorke’s Drift, Lady Elizabeth Butler, 1880

In “Penelope”, Molly recalls reading and re-reading Lieutenant Mulvey’s letter “while father was up at the drill instructing” around the time she was 15. Gifford and Seidman note that drill instruction would have been the duty of a sergeant-major and thus beneath the rank of major. We know that Tweedy was fine fudging other details, both large and small, of his life, so maybe he was indeed a sergeant-major, but shortened it to just “major” when he left Gibraltar.

Richard Ellmann wrote in his biography of Joyce that Major Tweedy was inspired by a family friend called Major Powell, whose title of “major” was disputable at best. It’s unclear if Major Powell was as creative with the truth as Tweedy, though. It’s my feeling that Joyce wanted to spoof this idiosyncratic old man in his novel, putting in just enough detail that the sharp-eyed reader would pick up what Bloom didn’t - the old major is full of b.s. One final fun fact: Major Powell retired in Clondalkin which has a townland called Gibraltar. I don’t know if this inspired the location of Molly’s girlhood home for Joyce, however.

Von Phul posits a compelling theory about what Major Tweedy was doing in Gibraltar all those years - rather than a major, he may have been a drum major, or bandleader, for the military brass band. She believes that while Tweedy never set foot in Plevna, he very well could have been in Rorke’s Drift, but not as a soldier. Tweedy may have been one of the patients in the hospital that were protected by defending soldiers. The officers present were promoted to major, but as Tweedy was just another man from the ranks, they rewarded him with the plumb position of drum major in Gibraltar, affording him better pay and a home base in Gibraltar with Molly.

This hypothesis is based in part on the assumption that Molly got her musical skill from her father, as the position of drum major would require the ability to read music and play brass instruments. On top of this, Molly recalls going around “on an officers arm… on bandnight.” Von Phul said it was customary for the band leader’s “lady” to be escorted by an officer during concerts. Since her mother was out of the picture, young Molly got to play the lady on these evenings, to the great envy of the “sparrowfarts.” Again, Molly refers to herself as a “soldiers daughter” in this recollection, which would have occurred post-Rorke’s Drift. Finally, it’s possible that the members of the band might have referred to Tweedy as “Major” and the title stuck. By the time he came to Dublin, he was well established as “Major Tweedy.” No one bothered to question him, including his son-in-law.

Bloom’s memories of Major Tweedy in “Calypso” are almost totally bunk, then, as he wasn’t a true major, had never been to Plevna, and the bed had belonged to an itchy old man rather than a governor. What of Bloom’s thoughts about Tweedy in “Lotus Eaters”? Let’s take a look:

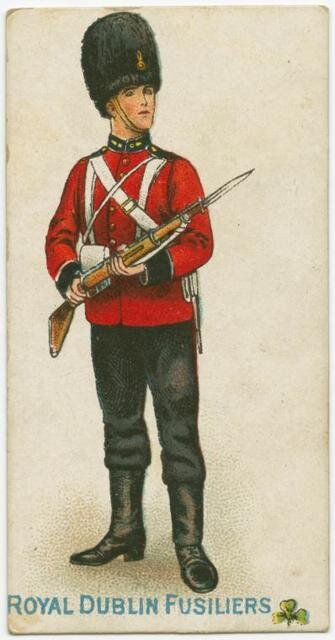

“He slipped card and letter into his sidepocket, reviewing again the soldiers on parade. Where's old Tweedy's regiment? Castoff soldier. There: bearskin cap and hackle plume. No, he's a grenadier. Pointed cuffs. There he is: royal Dublin fusiliers. Redcoats. Too showy. That must be why the women go after them. Uniform. Easier to enlist and drill.”

As Bloom scans for the old major’s regiment on a recruiting poster in the post office, he analyzes the men’s uniforms. Gifford and Seidman point out that Bloom is confusing the uniform of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers with that of the Grenadier Guards. It’s questionable given Tweedy’s timeline in Gibraltar and his casual relationship with the truth if he was even a member of the RDF. They were indeed stationed in Gibraltar at one time, but only for a year in 1884. It seems unlikely that Tweedy would have been stationed there with the RDF, especially considering his daughter Molly was born there in 1870 and the unit wasn’t founded until 1881. Maybe he joined after their founding? Maybe, but I’m personally suspicious of anything in Tweedy’s background that doesn’t quite add up.

“Maud Gonne's letter about taking them off O'Connell street at night: disgrace to our Irish capital.”

There’s nothing about Tweedy here, but we do get an interesting side story about Irish revolutionary Maud Gonne’s activism in the early 20th century. During the Boer War, the British Army tried to boost enlistment by not requiring men stationed in Dublin to stay in the barracks at night. This led to all sorts of wanton acts with the prostitutes of Dublin. Gonne wrote in her autobiography, A Servant of the Queen, that “...O’Connell Street at night used to be full of Red Coats walking with their girls.” She and members of her organization, Inghinidhe na hÉireann (Daughters of Ireland), took to the streets, handing out pamphlets to couples condemning “Irish girls consorting with the enemy of their country.” It all feels kind of gross to me, looking back from the 21st century - essentially slut-shaming impoverished women for doing what they needed to survive. Accosting people on the street turned out to be quite controversial in its day as well, as Gonne’s group traveled in the company of male “guards” to defend them when inevitable altercations arose. I think this tossed off comment from Bloom foreshadows Stephen’s run-in with the English privates Carr and Compton in “Circe.”

“Griffith's paper is on the same tack now: an army rotten with venereal disease: overseas or halfseasover empire. Half baked they look: hypnotised like. Eyes front. Mark time. Table: able. Bed: ed.”

Bloom note’s Sinn Fein founder Arthur Griffith’s nationalist paper The United Irishman opposed the soldiers’ presence as well. Bloom works for The Freeman’s Journal, another nationalist paper, but his own opinion this particular issue is often ambivalent, at least in part due to his family connection to the military. However, he’s clearly no loyalist based on his unflattering comments here about the Empire’s armed forces.

The soldiers on the recruiting poster are correspondents for the Lotus Eaters that ensnared Odysseus’ men in The Odyssey. Here Bloom perceives the men on the poster in the context of the hypnotising vices of sex and booze, “halfseasover” meaning drunk. He imagines them at drill practice, doing as they’re told by some bossy sergeant-major: “Eyes front. Mark time.” Those last few syllables ( “Table: able. Bed: ed”) are meant to be chants used while marching. The men following the orders are trained not to think for themselves. This particular lotus doesn’t offer physical comfort, but perhaps it numbs the distress of having to make difficult decisions. All you have to do is obey (and try not to get your head blown off). And if that causes you stress, go ahead dull those bad vibes with sex and booze.

“The King's own. Never see him dressed up as a fireman or a bobby. A mason, yes.”

Edward VII in freemason apron

It’s not just common men who find comfort in the authoritarian structure of the military. King Edward VII himself liked to dress in military garb, though Bloom astutely notes that he didn’t honor firemen or policemen in the same way. Edward VII was indeed a freemason; he was Grand Master of the United Grand Lodge of England between 1874 and when he ascended to the throne in 1901.

Further Reading:

Ellmann, R. (1959). James Joyce. Oxford University Press.

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/vy6j4tk

Tierney, Andrew. (2013). “‘One of Britain’s fighting men’: Major Malachi Powell and Ulysses.” James Joyce Online Notes. Retrieved from http://www.jjon.org/jioyce-s-people/powell

Von Phul, R. (1982). "Major" Tweedy and His Daughter. James Joyce Quarterly, 19(3), 341-348. Retrieved October 6, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25476450