Ulysses & The Odyssey - The Lestrygonians

“I have just got a letter asking why I don’t give Bloom a rest. The writer of it wants more Stephen. But Stephen no longer interested me to the same extreme. He has a shape that can’t be changed.” - James Joyce to Frank Budgen

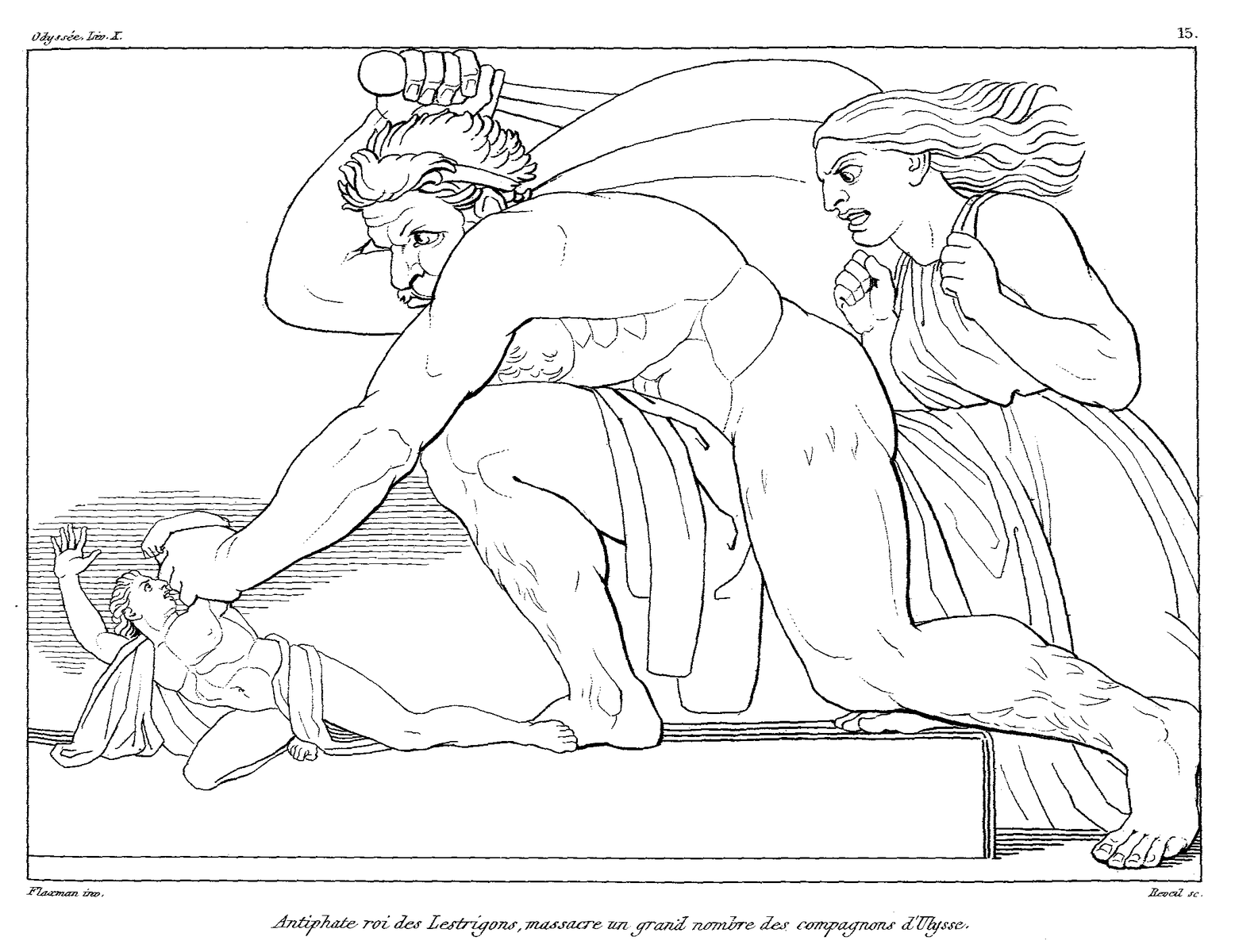

The Odyssey - Book X

After their dust-up with Aeolus, Odysseus and his crew are feeling pretty low. Worse still, the winds refuse to aid them, so they must row day and night. After a week solid of rowing, they try to take refuge in Lamos, the land of the Lestrygonians. Odysseus sends some of his crew to scope things out, and they are brought to the house of Antiphates, king of the Lestrygonians. In a terrible twist, the Lestrygonians turn out to be hideous, man-eating ogres. They devour most of his men and sink all but one of his ships. Odysseus and his surviving crew flee for their lives.

At the opening of “Lestrygonians”, the eighth episode of Ulysses, the newsmen and Stephen have all tottered off to their liquid lunch. After such a crowded and boisterous episode as “Aeolus”, we find ourselves back inside the head of Mr. Leopold Bloom, treated to his (mostly) uninterrupted stream of consciousness monologue as he journeys from the Freeman’s Journal offices north of the Liffey to Davy Byrne’s restaurant to the south. He passes a few famous Dublin landmarks on the way, but it’s his quirky observations and wistful reflections that make this episode memorable. James Joyce told his friend Frank Budgen that “Bloom should grow upon the reader throughout the day” as we eavesdrop on his thoughts. Joyce said that while his protagonist is not particularly brilliant, he is always “singular, organic, Bloomesque,” three qualities that this episode has in spades.

Despite its gruesome barbarity, the Lestrygonians’ appearance in The Odyssey is fairly brief, so there aren’t many characters to map onto Ulysses’ eighth episode. The Homeric parallel mainly surfaces as direct and indirect references to Bloom’s nagging hunger. He’s waited a little too long for lunch, so his rumbly tummy won’t quite let him be. A delayed dinner can be enough to turn a mild-mannered gentleman fully lestrygonian if not tended to soon enough. “Eat or be eaten! Kill! Kill!” It’s enough to convert a vegan to carnivore. We see the full manifestation of the Lestrygonians as the messy, chaotic diners in the Burton restaurant. While we all have a hangry little ogre inside us that rears its head from time to time, Bloom is able to resist and control his inner Lestrygonian.

Blazes Boylan

Bloom is pursued by his own correspondent Antiphates in the form of Blazes Boylan, who keeps cropping up in his thoughts and then in the flesh in the finale of the episode. In Les Phéniciens et l’Odysée (a favorite of Joyce’s), Victor Bérard says that “Antiphates” derives from a word meaning “accuser, backbiter, slanderer.” Joyce incorporated this interpretation into the character of Boylan, who is described in Joyce’s notes as “blasphemer, accuser, curser (Boylan).” Blazes’ overindulgence tends more towards lust than gluttony, though. He may be the worst man in Dublin, but as far as I know, he’s never eaten anyone.

Both Bérard and Joyce scholar Richard Ellmann point to the importance of anthropomorphic geography in making sense of the Lestrygonians encounter, whether in Homer or Joyce. Bérard, writing in French, tried to capture the near-sentient qualities of the ancient Greek landscape often lost in English translations. In Homer’s version of the Mediterranean, the land itself hungers. For instance, Bérard characterized the narrow inlet leading to Lamos as an open mouth leading to a goulet (bottleneck), also evoking the English word “gullet.” Odysseus’ men are then led sur une route plate (on a flat road) to the court of Antiphates, the pun on the word plate easily guessable even for non-French-speakers.

The land beneath Bloom’s feet may not hunger for him, but every other contour of the episode is purposely packed with a preponderance of food imagery. Joyce told Budgen that it’s notable, for instance, that Bloom refers to Molly’s legs as “out of plumb” in this episode. Thus spake Joyce:

“At another time [Bloom] might have expressed the same thought without any underthought of food. But I want the reader to understand always through suggestion rather than direct statement.”

This quality of non-food items acquiring foodlike qualities is called “trophomorphism”. It’s a high-falutin' version of when the Looney Tunes see their friend turn into a big chicken leg when they’re starving. Once you’re aware of it, you’ll see it everywhere in “Lestrygonians.”

Ellmann takes the image of two towering headlands and narrow fjord that lead to Lamos and applies it thematically to Joyce’s “Lestrygonians”. Bloom navigates a channel between his persistent thoughts and encounters with food and sexuality in this episode, some of which are nice, while others are downright lestrygonian.

The first metaphoric headland, food, was also of great importance to the ancient Greeks. What a nation eats defines its character in many instances in The Odyssey. We’ve already encountered the Lotus Eaters, corrupted by their soporific suppers. Odysseus and his crew identify as “men who live on the earth by bread” as a way of separating themselves from the many supernatural entities they meet on their travels. We now meet the Lestrygonians, a nation of vile, ravening cannibals.

The dark side of hunger reveals itself in ways great and small during Bloom’s walk to the safe harbor of Davy Byrne’s. The lestrygonian impulse can be seen in the greedy, ungrateful gulls that snap up Bloom’s banbury cakes and in the rats he imagines drinking and vomiting all over the Guinness barge. It’s there in the racist rhyme about Mr. MacTrigger and in the vision of the communal souppot as big as Phoenix Park, itself reminiscent of the ring of the bay that traps Odysseus’ men. If hunger is not sated, it can lead to the quiet tragedy of the malnourished Dedalus children, represented by Dilly Dedalus selling the family’s possessions in the auction house.

Just as he did in “Lotus Eaters”, Bloom can’t help but notice the bloodthirstiness of power, both sacred and secular. He has a religious throwaway thrust into his hands that reads “Blood of the Lamb” followed by the sight of a Christian Brother indulging in some disgustingly sweet ice cream. This leads to Bloom imagining a king “sucking red jujubes white,” further combining a too-sweet childish treat with the color of blood. Bloom’s horror and disgust at the parade of bloody metaphors he encounters on the way to lunch convinces him to seek out a vegetarian option in the end - a nice cheese sandwich.

John Flaxman, Jr., 1810

Bloom is also oppressed by the headland of sex, the other appetite he can’t quite shake during his lunch hour. For his Homeric counterparts, it was the cajoling of Antiphates’ daughter that eased the fears of Odysseus’ men before leading them to their doom. Hidden seduction slinks through Bloom’s mind as he traverses the city center. Bloom is preoccupied throughout much of the episode by memories of happier days with Molly, which are supplanted by thoughts of her affair with Boylan, and then in turn interrupted by thoughts of Martha’s naughty letter. Joyce intentionally developed this seduction motif throughout the episode in the same way he did the hunger motif. In one scene, Bloom’s mind reels from the sight of some sexy petticoats in a window:

“Perfume of embraces all him assailed. With hungered flesh obscurely, he mutely craved to adore.”

To Joyce, this floating, intoxicating “perfume” is the form taken by Antiphates’ daughter, luring men to their doom. Joyce told Budgen that he had agonized over these two sentences for a full day to perfectly represent this motif, saying that the words came to him easily enough, but the task of “arranging” them correctly was excruciating. As a side note, scholar Hugh Kenner thinks this oft-repeated anecdote doesn’t match up with evidence in Joyce’s manuscripts, so take it with a grain of salt. In any case, Bloom, like Odysseus, once again maintains his discipline in the face of so much temptation and is able to sail away intact from his encounter with the Lestrygonians.

The motifs of food and sex merge in the image of seedcake in one of Bloom’s most vivid memories - the day he and Molly made love under the rhododendrons on Howth:

“Ravished over her I lay, full lips full open, kissed her mouth. Yum. Softly she gave me in my mouth the seedcake warm and chewed. Mawkish pulp her mouth had mumbled sweetsour of her spittle. Joy: I ate it: joy. Young life, her lips that gave me pouting. Soft warm sticky gumjelly lips. Flowers her eyes were, take me, willing eyes. Pebbles fell. She lay still. A goat. No-one. High on Ben Howth rhododendrons a nannygoat walking surefooted, dropping currants. Screened under ferns she laughed warmfolded. Wildly I lay on her, kissed her: eyes, her lips, her stretched neck beating, woman’s breasts full in her blouse of nun’s veiling, fat nipples upright. Hot I tongued her. She kissed me. I was kissed. All yielding she tossed my hair. Kissed, she kissed me.”

The image of fermentation - “Mawkish pulp her mouth had mumbled sweetsour of her spittle.” - is where the intersection of food an sex lie for Joyce. He told Budgen:

“Fermented drink must have had a sexual origin…. In a woman’s mouth, probably. I have made Bloom eat Molly’s chewed seed cake.”

I suppose it’s apropos that Bloom reminisces over a glass of Burgundy.

Ellmann sees powerful, emotional memories like this as Bloom’s most powerful weapon against the Lestrygonians. It’s his sensitivity that allows him to maintain possession of his sense of self against a hostile and irrational world:

“Love animates his imaginative memory and allows him to bring forth a succulent tidbit from his mental larder.”

Bloom, like Odysseus, is trying to find his way home. His love for Molly is his North Star, if he can manage to find her in all the din and distraction around him. The way is fraught, though. This beautiful, romantic scene opens and closes with the image of two buzzing flies “stuck” together on a window pane. They are a filthy image in contrast to the sensuous world of Howth and the seed cake, but they may be a signal to Bloom’s future as well. If not treated with respect, food and sex can both lead to “indigestion” of sorts. At some point, maybe husbands and wives are just stuck with one another.

Further Reading:

Budgen, F. (1972). James Joyce and the making of Ulysses, and other writings. London: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AMF2PZFZHI2WND8U

Childress, L. D. (1989). “Les Phéniciens et l’Odyssée”: A Source for “Lestrygonians.” James Joyce Quarterly, 26(2), 259–269. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25484946

Ellmann, R. (1972). Ulysses on the Liffey. Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.65767/2015.65767.Ulysses-On-The-Liffey_djvu.txt

Homer, translated by Palmer., G.H. (1912). The Odyssey. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications.

Gilbert, S. (1955). James Joyce’s Ulysses: a study. New York: Vintage Books. Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.124373/page/n3/mode/2up

Kenner, H. (1987). Ulysses. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Romanoff, A. Lestrygonians-Modernism Lab. Retrieved from https://campuspress.yale.edu/modernismlab/lestrygonians/

Schwarz, D. (2004). Reading Joyce’s Ulysses. Palgrave Macmillan.