Decoding Dedalus: Folly. Persist.

This is a post in a series called Decoding Dedalus where I take a passage of Ulysses and break it down line by line.

The line below comes from “Scylla and Charybdis,” the ninth episode of Ulysses. It appears on page p. 184-185 in my copy (1990 Vintage International). We’ll be looking at the passage that begins “—Monsieur de la Palice…” and ends “Folly. Persist”

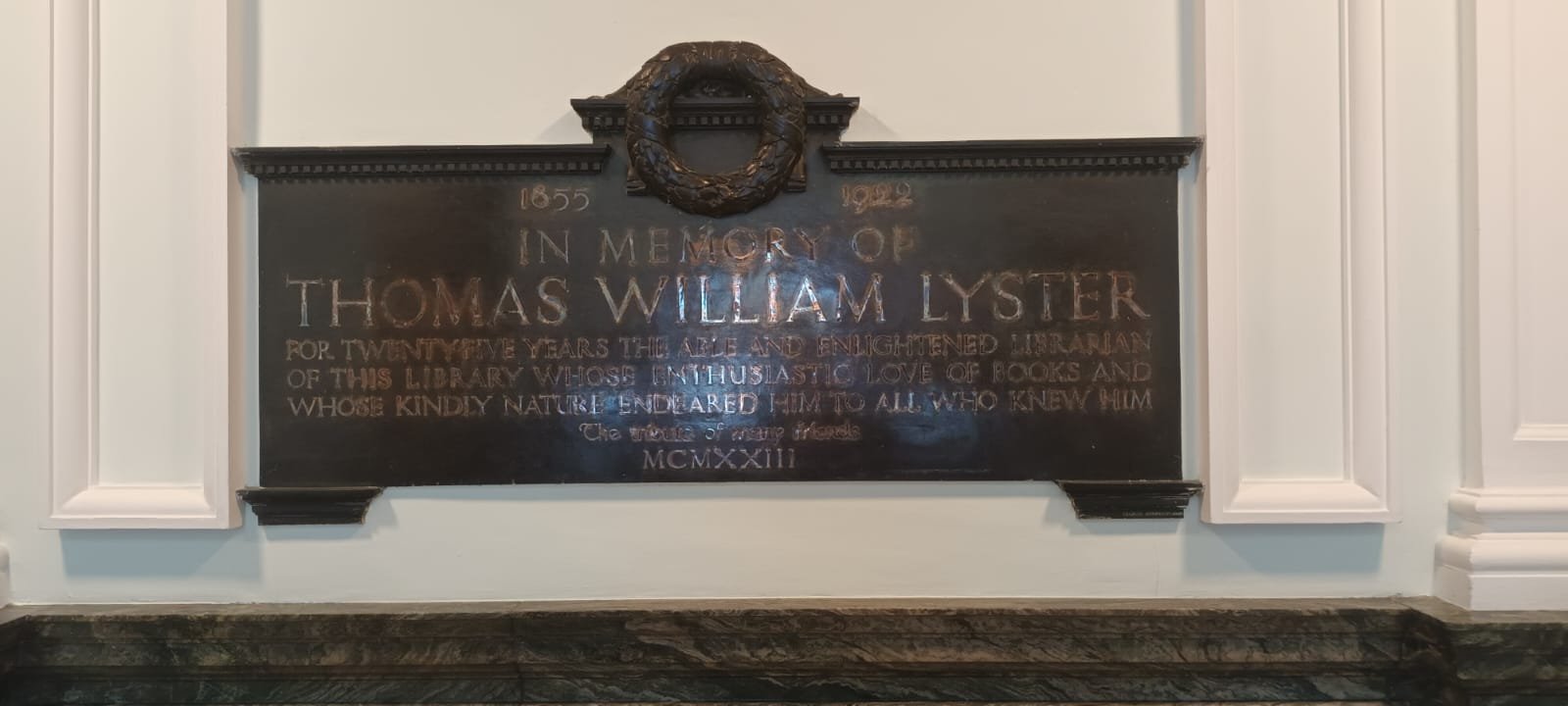

National Library of Ireland, July 2024

“Scylla and Charybdis”, Ulysses’ ninth episode, opens with head librarian Thomas Lyster sharing his thoughts on Wolfgang von Goethe’s novel Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship and Travels. Heinrich Dunzter’s Life of Goethe was translated by the real-life Lyster, so his fictional counterpart offers his expertise on the subject here. In Goethe’s novel, the titular Wilhelm Meister translates and comments on Hamlet, so Lyster’s brief comments in this section prime us for Stephen Dedalus’ “translation” of sorts of Hamlet. Much like Wilhelm Meister, Stephen’s theories and opinions on Hamlet will reflect those of his creator. Following Lyster’s remarks, Stephen makes a snarky retort and the episode unfolds from there:

“—Monsieur de la Palice, Stephen sneered, was alive fifteen minutes before his death.”

James Joyce never could resist a pun, certainly not a pun that lets you know that he’s been to Paris.

M. de la Palice, fifteen minutes before his death

Monsieur Jacques de la Palice, or Lapalisse depending on who you ask, was a French nobleman who died at the Battle of Pavia in 1525. Whatever Monsieur de la Palice’s accomplishments in life were, he’s remembered now for having a mildly amusing tombstone. His epitaph reads:

“Ci-gît le Seigneur de La Palice: S’il n'était pas mort, il ferait encore envie.”

"Here lies Sir de la Palice: If he weren't dead, he would be still envied."

The thing is, “f” in “ferait” kind of looks like an “s” in the inscription, and the word “envie” kind of sounds like the phrase “en vie.” If you tweak this guy’s epitaph just so, it becomes:

"...il serait encore en vie"

"...he would still be alive"

Hilarious.

Or at least, it’s memorable enough to become an expression meaning a truism or tautology; in fact, “lapalissade” has come to mean “truism” in French. While La Palice’s tomb was destroyed during the French Revolution, his epitaph’s memory lingered on in a song from the early 18th century.

For our purposes, Stephen, underwhelmed with Lyster’s praise of Goethe, more or less responds, “Well, duh.” I imagine Stephen picked this expression up during his disastrous sojourn to Paris and is flexing his shred of worldliness here among the library men he’d love to impress. The arrogance displayed in this snarky aside opens Stephen to attack:

—Have you found those six brave medicals, John Eglinton asked with elder’s gall, to write Paradise Lost at your dictation? The Sorrows of Satan he calls it.

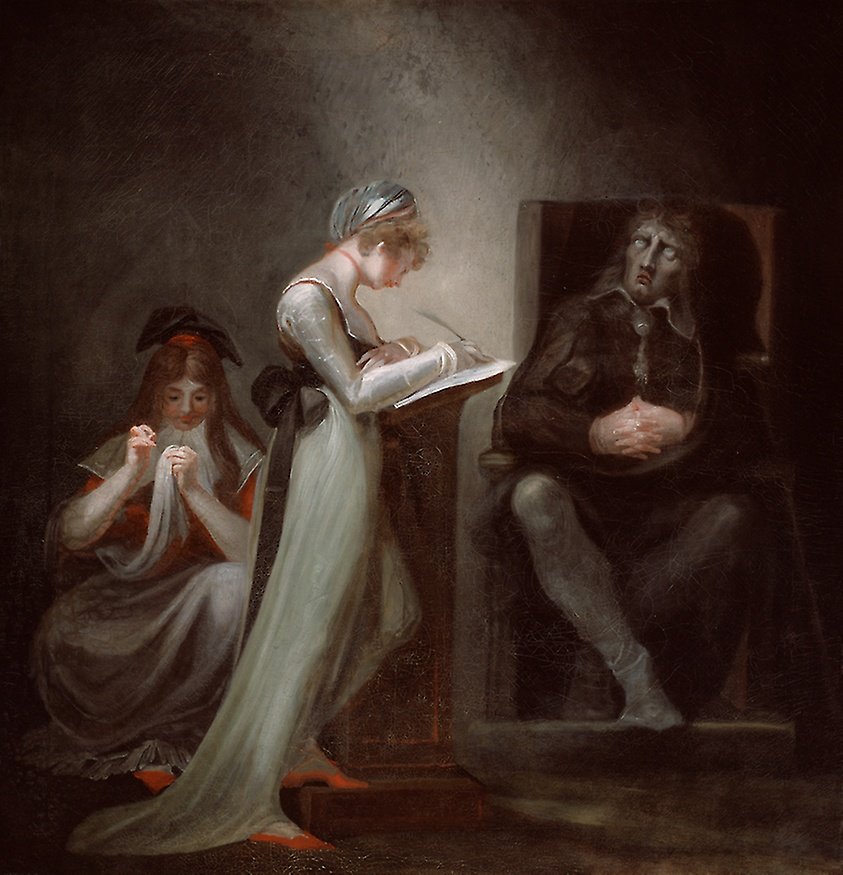

Milton Dictating to His Daughter, Henry Fuseli (1794)

John Eglinton references two works of literature here - one quite famous and the other obscure. We can first unravel the mystery of the six brave medicals by delving into Joyce’s notes for his unfinished novel Stephen Hero in his so-called Pola Notebook:

“Six brave medical students under my direction will write Paradise Lost except 100 lines [sic].”

The six brave medical students may be an allusion to the six crewmen devoured by Scylla as Odysseus’s ships passed beneath her treacherous rocks. As far as Paradise Lost is concerned, John Milton was blind during the period in which he wrote his epic poem and employed his daughters as amanuenses, or scribes, to do the physical act of writing while he dictated. Assuming this was a real idea that Stephen confessed to the Eglinton, perhaps he has rightly clocked that our young Artist was attempting a bit of Milton cosplay in this odd endeavor, mimicking the activities of a literary giant in the vain hope that this would somehow translate into his own literary triumph. Setting half a dozen men of science to a job better suited to men of Art would seem to be a task doomed to fail, especially if Stephen’s Shining Six were anything like the rowdy medical students we meet in “Oxen of the Sun.” It would also imply that he’s grasping at straws, recruiting students from his college due to his lack of contacts among the literary set. It’s easy to see why Stephen finds this remark galling.

You’d be forgiven for missing the significance of The Sorrows of Satan, but its inclusion bolsters Ulysses as a feat of intertextuality, seamlessly weaving Milton, Shakespeare, Homer and Dante with utter garbage. The Sorrows of Satan is an 1895 novel by Marie Corelli that tells the story of Geoffrey Tempest, a man who accidentally makes a Faustian deal with the devil and is saved by a wholesome, benevolent Christian author named Mavis Clare. The twist (spoiler alert) is that Tempest has panned Clare’s books in the past but learns the error of his ways through her Christian grace. Many of Corelli’s novels followed the pattern above, replete with petty score-settling and literal come-to-Jesus epiphanies.

Corelli waged a lifelong war against book critics, refusing to send out review copies of her books, because at least she’d make a sale off anyone who wrote a negative review. Mavis Clare was a self-insert character for Marie Corelli, who was truly the Kirk Cameron of her day. Like Cameron, Corelli was a fundamentalist Christian who vehemently opposed libraries, as she felt they spread disease and worse still, allowed people to read her books for free. As readers of Ulysses, we can appreciate the irony of her most famous book being referenced in a literal library. To Corelli’s credit, The Sorrows of Satan was a best-seller in its day and popularized the name Mavis in wider culture. It was also turned into a film by D.W. Griffith, who also made Birth of a Nation, so do with that information what you will.

Stephen just can’t catch a break from Eglinton. He’s getting mocked for likening himself to Milton, a pretty big swing for an unknown, young writer in fairness, and now he’s being compared to Corelli, the type of hack every aspiring Artist secretly worries they might truly be. In fairness to Corelli, Joyce did adopt her habit of literary score-settling in his own masterpiece, in this very scene, so maybe she was onto something. And surely much to Ms. Corelli’s chagrin, Joyce uses the title of her novel, along with Paradise Lost, to introduce a satanic motif that runs throughout this passage. More on that momentarily.

Smile. Smile Cranly’s smile.

First he tickled her

Then he patted her

Then he passed the female catheter

For he was a medical

Jolly old medi...

Irritated by Eglinton’s jibes, Stephen’s mind flashes to the past betrayals of his former friend Cranly and then Buck Mulligan, in the form of his rude poem, “The Song of Medical Dick and Medical Davy.” To me, this implies that Stephen wants Eglinton’s approval but feels slighted when all he gets is teasing in response to his miscalculated intellectual bids.

You can read about Stephen’s fraught relationship to Cranly here, and his fraught relationship to Medical Dick and Medical Davy here. There’s no word on whether Medical Dick and Medical Davy were among Stephen’s would-be amanuenses.

—I feel you would need one more for Hamlet. Seven is dear to the mystic mind. The shining seven W.B. calls them.

Glittereyed his rufous skull close to his greencapped desklamp sought the face bearded amid darkgreener shadow, an ollav, holyeyed. He laughed low: a sizar’s laugh of Trinity: unanswered.

The “rufous skull” belongs to the auburn-haired Eglinton, but the “face bearded” belongs to Æ, master of mystics, octopuses and agrarian reform, who once more rears his head on the page. The speaker in this passage is ambiguous, but it feels to me that naturally Æ would be dispensing some mystical wisdom as our Platonic stand-in. He helps move the discussion from Milton to Shakespeare, and away from tormenting poor Stephen. Here, he alludes to W.B. Yeats’ poem, “A Cradle Song,” though he gets the line slightly wrong:

“God's laughing in Heaven/ To see you so good;

The Sailing Seven/ Are gay with His mood.”

This passage highlights the intentionally ambiguous use of initials in “Scylla and Charybdis” (really, in all of Ulysses) allowing for densely layered allusions to be jam packed into every letter. In the book Occult Joyce, scholar Enrico Terrinoni likens this aspect of Joyce’s writing to a medium at a séance, though notes such a process is thoroughly parodied by Joyce. The medium analogy is fitting, however, as Joyce wades into explicitly occult territory in this passage. Another W.B. with an occult bent also wrote a poem called “A Cradle Song” - William Blake. Furthermore, Blake also references “the starry seven” in his epic poem Milton. Though Blake’s “A Cradle Song” doesn’t contain a line similar to Æ’s quote here, we become aware of an overlap of the two W.B.’s as we move through the episode, creating an enticing synthesis with each subsequent reference, allowing Æ to quote two W.B.’s simultaneously. This allusion, then is actually reinforced by the misquote, since it’s not quite perfectly either W.B. These overlapping allusions allow for more complex interpretations of these passages, much like the use of metempsychosis to draw historical and literary parallels to various Ulysses characters.

Turning to the substance of Æ’s statement, he is absolutely correct – the number seven is indeed very dear to the mystic mind. There are too many implications of this number to mention all of them, though Terrinoni notes the seven colors, the seven notes of a musical scale, the seven numerals of Pythagoras, the seven wonders of the world and the seven steps of the Masons among many, many others. Yeats’ sailing seven are the seven planets recognized at the time he composed the poem. Notably, the Catholic Church holds the number seven sacred as well, as evidenced by the Seven Sacraments, Seven Virtues, and Seven Deadly Sins.

Orchestral Satan, weeping many a rood

Tears such as angels weep.

Ed egli avea del cul fatto trombetta.He holds my follies hostage.

These lines are Stephen’s internal riposte to Eglinton and Æ’s commentary on his youthful literary “follies.” Stephen realizes the medical thing wasn’t a good idea, one to be left on the shelf with his alphabet books, but now these older influential men are holding his follies hostage, so to speak, discussing them as if they were something serious (and notably not discussing Stephen’s current work).

Detail from The Garden of Earthly Delights, Hieronymous Bosch, 1490-1510

Stephen paraphrases a bit more of Paradise Lost, once more with a focus on Satan, and then throwing in some Dante for a line of (Divine) comedic effect. The Italian is once more taken from The Divine Comedy and translates to something along the lines of “And he made a trumpet of his ass.” It is spoken by the devil Malacoda as he heralds the departure of the fictional Dante and Virgil on their long journey. Malacoda’s ass trumpet can be heard reverberating throughout Ulysses backwards and forwards in time with this moment as its epicenter. Its echo can be heard in Bloom’s fart at the end of “Sirens,” in the query “Mr. Editor, what is a good cure for flatulence?” in “Aeolus”, and in the bawdy language of the Italian ice cream vendors in “Eumaeus.” What does it herald for our Stephen? In its immediate aftermath, anyway, just more thoughts of Cranly:

Cranly’s eleven true Wicklowmen to free their sireland. Gaptoothed Kathleen, her four beautiful green fields, the stranger in her house. And one more to hail him: ave, rabbi: the Tinahely twelve. In the shadow of the glen he cooees for them. My soul’s youth I gave him, night by night. God speed. Good hunting.

Mulligan has my telegram.

Folly. Persist.

Stephen redirects his thoughts to one of Cranly’s own follies, and then to one of W.B.’s. Cranly’s assertion that eleven (really twelve) men from Wicklow doesn’t appear anywhere in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, the only literary work in which Cranly appears as a character. Richard Ellmann notes in his biography of Joyce that this assertion was made by Joyce’s friend J.F. Byrne, upon whom Cranly was based. Byrne, and thus Cranly, had roots in Wicklow and was proud of his county’s rebellious history, as some of the bloodiest battles of the 1798 Rebellion raged in Co. Wicklow. Cranly (and Byrne) is being mocked here for his youthful idealism. It’s implied that the twelfth man would be Cranly himself:

“And one more to hail him: ave, rabbi: the Tinahely twelve.”

An Sean Bhean Bhocht

Cranly is the “one more to hail him.” He speaks, “Ave, Rabbi,” Judas’ words to Jesus just before kissing him in Gethsemane in the ultimate betrayal. The line just before alludes to “the stranger in her house,” which would generally mean the British colonial government (the stranger) in “her” (Ireland’s) house. Ireland is personified her as “gaptoothed Kathleen,” an allusion to the W.B. play Cathleen ní Houlihan, in which the elderly, beaten down Cathleen symbolizes Ireland and “her four beautiful green fields,” or the four provinces of Ireland. The “sean bhean bhocht” (poor old woman) as an allegory for Ireland has already been parodied in Ulysses as the old milk woman in “Telemachus.” Kathleen is gaptoothed here because she is elderly, yes, but she is also gaptoothed because she is from Wicklow. The Irish language name for Wicklow is Cill Mhantáin, which is related to the Irish word for gaptoothed or toothless, mantach. Legend has it Mantan was a follower of St. Patrick who had his teeth knocked out in an altercation when Patrick first landed in Wicklow. Mantan would go on to found the church in Cill Mhantáin, meaning Mantan’s Church or the Church of the Toothless One. In the Shadow of the Glen is a one-act play by J.M. Synge set in, you guessed it, Wicklow. Stephen is laying it on a bit thick here.

Naturally, Stephen’s residual bitterness towards Cranly turns to thoughts of Mulligan once more. Stephen is trying to psych himself up to defend his Shakespeare theory to these older men, who are already poking fun at his old literary follies. Stephen’s insecurity in the moment is compounded by the mockery he suffered at the hands of other so-called friends, Cranly and Mulligan. He is able to muster his courage in the end, thinking, “Folly. Persist.” and pushing forward.

Significantly, in the midst of this inner turmoil, Stephen thinks of Cranly, “My soul’s youth I gave him, night by night.” This sentiment is echoed in a letter Joyce wrote to Nora in 1904 regarding Byrne:

“When I was younger I had a friend to whom I gave myself freely – in a way more than I give to you and in a way less. He was Irish, that is to say, he was false to me”.

Portrait dramatizes how Stephen confessed to Cranly many of his innermost concerns and anxieties, including his lost faith and his unwillingness to pray with his then-living mother. Cranly pushed back, arguing that there is nothing so pure in this world as a mother’s love and that such a love should be honored, just as Byrne did against Joyce in real life. Mulligan, by contrast, just said that Stephen’s mother is beastly dead. Stephen ultimately rejects Cranly’s advice and much of Stephen’s inner turmoil on Bloomsday is due to his refusal to pray with his mother once more, this time at her deathbed, which is why he’s so haunted by Cranly in this particular moment. He may even see the face of his ailing mother in the stereotypical image of An Sean Bhean Bhocht, as he rejects both his mother’s religion and his Motherland.

I think this is also why the allusions to Paradise Lost and Satan are bubbling up here. Stephen told Cranly when pressed that he would not pray because “[he] will not serve,” echoing Satan’s words in Fr. Arnall’s fire and brimstone sermon from Portrait. Stephen will of course utter the Latin version of Satan’s phrase again at the climax of Ulysses, “Non serviam.” Stephen does have a, if not exactly Satanic then certainly Luciferian, quality. He has rejected authority and struck out on his own, dresses all in black, and is doing his level best to reject Christianity. He awakes next to Dublin Bay’s “bowl of bitter waters” just as Satan awakes in a lake of fire in Paradise Lost. If you really want to belabor the analogy, you can even liken Stephen’s ashplant to Satan’s spear.

Terrinoni notes one peculiarly Luciferian moment for Stephen from Portrait:

“Yes, his mother was hostile to the idea, as he had read from her listless silence. Yet her mistrust pricked him more keenly than his father’s pride and he thought coldly how he had watched the faith which was fading down in his soul ageing and strengthening in her eyes. A dim antagonism gathered force within him and darkened his mind as a cloud against her disloyalty and when it passed, cloudlike, leaving his mind serene and dutiful towards her again, he was made aware dimly and without regret of a first noiseless sundering of their lives.”

On the heels of this passage, Stephen experiences a strange vision or hallucination while walking on the strand:

“It seemed to him that he heard notes of fitful music leaping upwards a tone and downwards a diminished fourth, upwards a tone and downwards a major third, like triple-branching flames leaping fitfully, flame after flame, out of a midnight wood. It was an elfin prelude, endless and formless; and, as it grew wilder and faster, the flames leaping out of time, he seemed to hear from under the boughs and grasses wild creatures racing, their feet pattering like rain upon the leaves.”

Also a Slayer album

Terrinoni notes that the musical intervals described here are three-tone intervals known as tritones and also as Diabolus in Musica - the Devil in Music. The use of these particular musical intervals was prohibited by the Church until the end of the Renaissance. Legend has it that such music would summon Satan himself. Furthermore, it was rumored that anyone caught playing these notes could be tortured or even burned at the stake for their crimes. While Stephen is not playing these notes, it’s significant that he is spontaneously hearing the Diabolus in Musica, enticing and courting him as he wavers in his Christian faith.

While Stephen ultimately rejects the priesthood for the life of an Artist, he does not embrace Satan. While such rejection can be interpreted as an act of luciferian defiance, it is not defiance alone that animates Stephen, but rather a desire to “forge in the smithy of [his] soul the uncreated conscience of [his] race.” Stephen’s will is bent towards creation rather than destruction, though I think his lingering pain and bitterness surrounding Cranly and Mulligan diverts him momentarily when he loses himself in it. Even if Stephen was courted by Satan in Portrait, and while he’s still hyperborean in his way, and while he adopts “Non serviam” as his ethos, he also explicitly rejects Satan early in Ulysses. From Proteus:

“Clouding over. No black clouds anywhere, are there? Thunderstorm. Allbright he falls, proud lightning of the intellect, Lucifer, dico, qui nescit occasum. No. My cockle hat and staff and hismy sandal shoon. Where? To evening lands. Evening will find itself.”

For all his grief and struggle, the clouds don’t rule Stephen as he sets his own course. He flirts with the idea of identifying with Satan once more, and answers with a terse “No.” He strides forth to find his place among humanity, to have the strength and confidence to defend the integrity of his folly before the men in the library. Scholar Peter Dorsey writes:

“From a character who once thought that his mind was more interesting than all of Ireland, Stephen has become a character who recognizes that as the artist accepts himself, so he must accept all of humanity.”

Further Reading:

Crowley, R. (2006). "His Dark Materials": Joyce's "Scribblings" and the Notes for 'Circe' in the National Library of Ireland. Genetic Joyce Studies. Retrieved from https://www.geneticjoycestudies.org/articles/GJS6/GJS6Crowley

DEL GRECO LOBNER, C. (1993). “Sounds are Impostures”: From Patronymics to Dante’s “Trombetta.” Joyce Studies Annual, 4, 43–54. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26283684

Dorsey, P. (1989). From Hero to Portrait: The De-Christification of Stephen Dedalus. James Joyce Quarterly, 26(4), 505–513. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25484982

Ellmann, R. (1959). James Joyce. Oxford University Press.

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/vy6j4tk

Hogan, P. C. (1986). Lapsarian Odysseus: Joyce, Milton, and the Structure of “Ulysses.” James Joyce Quarterly, 24(1), 55–72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25476777

Pope, C. (2009, May 7). The Sorrows of Satan by Marie Corelli. Victorian Secrets. https://victoriansecrets.co.uk/the-sorrows-of-satan/

Schwarz, D. (2004). Reading Joyce’s Ulysses. Palgrave Macmillan.

Terrinoni, E. (2007). Occult Joyce: The hidden in Ulysses. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.