Rawhead and Bloody Bones in the Burton

“Although Joyce’s parallel reduces Homer’s ‘murderous reception’ to the farce of teeth chomping, a similar violence does exist here, if only in the poverty that has produced this scene…” - Trevor L. Williams

After passing through Grafton St. on the way to lunch in “Lestrygonians”, Ulysses’ eighth episode, Leopold Bloom must pass through one more horrific ordeal before he finds safe harbor in Davy Byrne’s moral pub. Bloom steps momentarily into the neighboring Burton restaurant, where he is repulsed by the deplorable table manners of a roomful of ravenous men. His encounter with the Burton diners parallels Odysseus’ catastrophic foray into the land of the Lestrygonians, a monstrous cannibalistic people that turn most of his fleet into brunch. Bloom's encounter with the Burton diners reveals more about the themes of Ulysses than just a Homeric Easter egg, though. He confronts a sight so petrifying, so shattering, it has the power to turn a man who relishes organ meats into a vegetarian and an ad canvasser into a communist (at least temporarily).

A Flood of Bloodhued Poplin

“A warm human plumpness settled down on his brain.”

Prior to the Burton debacle, Bloom passes through Grafton St., immersed in thirst for human flesh as he indulges in what Stephen Dedalus might consider morose delectation:

Grafton St. in the 19th c. (source)

“Grafton street gay with housed awnings lured his senses. Muslin prints, silkdames and dowagers, jingle of harnesses, hoofthuds lowringing in the baking causeway….

He passed, dallying, the windows of Brown Thomas, silk mercers. Cascades of ribbons. Flimsy China silks. A tilted urn poured from its mouth a flood of bloodhued poplin: lustrous blood….

Gleaming silks, petticoats on slim brass rails, rays of flat silk stockings.

Useless to go back. Had to be. Tell me all.

High voices. Sunwarm silk. Jingling harnesses. All for a woman, home and houses, silkwebs, silver, rich fruits spicy from Jaffa. Agendath Netaim. Wealth of the world.

A warm human plumpness settled down on his brain. His brain yielded. Perfume of embraces all him assailed. With hungered flesh obscurely, he mutely craved to adore.”

Any arousal Bloom feels from the window displays metamorphoses into a confused soup of anxiety about his own moribund sex life. The titillating reverie of “petticoats on slim brass rails” (perhaps on a rhythmically jingling bed all the way from Gibraltar) collapses under the weight of marital despair. He knows the lothario Blazes Boylan will be jingling the Blooms’ bed this afternoon. Even if he wanted to catch Molly and Blazes in the act, his deflated ego concludes it would be “useless to go back.” He considers becoming a man of action like Odysseus, but refuses the call. In a listless attempt at self-soothing, his mind transitions into “tell me all,” trying to conjure up Martha’s saucy letter. This is followed by a cascade of Orientalist imagery, recalling Bloom’s daydreams back in “Calypso.” Like Odysseus on Calypso’s island, though, Bloom can’t quite break free of the enormity of his misfortune.

While the silks are intoxicating, they also conceal a literal booby trap. Joyce saw Bloom’s momentary sexual distraction on Grafton St. as analogous to the allure of the Lestrygonian king’s daughter in The Odyssey. Her seduction lulled the sailors before the cannibalistic ambush that concluded their misadventure, their momentary passivity their downfall. There is also a whiff of things to come, with the Lestrygonian princess’ betrayal foreshadowed by the “bloodhued poplin: lustrous blood….” Bloom sees in the windows of Brown Thomas.

Bloom’s insecurity about his masculinity makes any attempt to interrupt Molly and Blazes’ tryst “useless.” As outsiders, we can imagine all sorts of ways that Bloom showing up at the house could be anything but useless, but he has chosen to retreat until a more favorable moment. Bloom’s inaction distinguishes him from both Odysseus and Blazes Boylan. He doesn’t display the smug gluttony of Boylan, but he also lacks the righteous wrath of Odysseus.

Molly, of course, has an active role as well. She and Blazes are both willing, active participants in their sex. Molly is actively consuming Blazes, too.

This one’s for all the Canadians in the audience.

Bloom’s mind is mired in the Bronze Age, though. In The Odyssey, the character of a nation is determined by what it eats. Sexual consumption and the consumption of food intermingle in Bloom’s imagination - “With hungered flesh obscurely, he mutely craved to adore.” Bloom can’t escape the mounting horror that he may actually be one of those annoying, ethereal veggie people, no matter how many kidneys and gizzards he gobbles up. Real Men must eat meat.

Men, Men, Men

Turning into Duke St., Bloom reaches his dining destination at long last: the Burton restaurant. However, as with Odysseus in the court of the Lestrygonians, things go horribly awry:

“His heart astir he pushed in the door of the Burton restaurant. Stink gripped his trembling breath: pungent meatjuice, slush of greens. See the animals feed.”

What unfolds is a disgusting caricature of Bloom’s idea of a masculine manly men - dirty, brutish, loud, mindless. This macho hellscape grips Bloom’s psyche. The men seem to change shape right before his eyes, twisting into gruesome, bestial forms:

“Perched on high stools by the bar, hats shoved back, at the tables calling for more bread no charge, swilling, wolfing gobfuls of sloppy food, their eyes bulging, wiping wetted moustaches… A man with an infant’s saucestained napkin tucked round him shovelled gurgling soup down his gullet. A man spitting back on his plate: halfmasticated gristle: gums: no teeth to chewchewchew it. Chump chop from the grill. Bolting to get it over.”

Cannibalistic desires reveal themselves as Bloom inches towards the door:

“Other chap telling him something with his mouth full. Sympathetic listener. Table talk. I munched hum un thu Unchster Bunk un Munchday. Ha? Did you, faith?”

Bloom was quick to feel superior to the ethereal vegetarians moments earlier, but when confronted with their carnivorous opposites, he bolts in terror. These men represent the dark aspects of manhood - aggressive, rapacious, insatiable, selfish. This outburst of unbridled masculinity unnerves Bloom further. He briefly panics, wondering if this is how he appears to others. At the end of the day, he too is a man. Do these dark impulses dwell deep within him? He panics:

“Am I like that? See ourselves as others see us.”

Though Bloom escapes physically unscathed, the insensible animal banquet in the Burton leaves him grasping for something to psychically steady himself. Once he is safely back on the street, Bloom transitions from revulsion to empathy, regaining his usual thoughtful demeanor. He ponders solutions to the detached cruelty of society at large:

“Suppose that communal kitchen years to come perhaps. All trotting down with porringers and tommycans to be filled. Devour contents in the street. John Howard Parnell example the provost of Trinity every mother’s son don’t talk of your provosts and provost of Trinity women and children cabmen priests parsons fieldmarshals archbishops. From Ailesbury road, Clyde road, artisans’ dwellings, north Dublin union, lord mayor in his gingerbread coach, old queen in a bathchair. My plate’s empty. After you with our incorporated drinkingcup. Like sir Philip Crampton’s fountain…. Have rows all the same. All for number one. Children fighting for the scrapings of the pot. Want a souppot as big as the Phoenix park.”

Bloom is reacting to the same societal paralysis as Stephen Dedalus. While Stephen feels the artistic and intellectual limitations imposed on him by the dominant culture, Bloom focuses on immediate, material needs of Dublin’s poorest citizens. He imagines a way to streamline feeding the multitudes, though he dejectedly supposes that the worst impulses of his fellow Dubliners would mar such an outpouring as the “eat or be eaten” mindset would eventually take over. The Burton was unnerving enough to turn the commercially-minded Bloom communist for a moment. Our Kidney King also briefly acquiesces to vegetarians in the next paragraph, so powerful was the bloody shock-horror of Dublin’s lestrygonian feast.

Bloom, ever moderate, does not favor radical action, though he does seem to realize the desperation of the people of Dublin. Hunger and predation are built into the system rather than manifesting as an occasional, regrettable byproduct. Bloom is not ready to fully embrace his role as a forward-thinking reformer as he does in “Circe,” and quickly abandons his political thoughts as he enters the sanctuary of Davy Byrne’s moral pub. Bloom has escaped for now, but we readers must dive further into the intellectual fire before finding our own safe harbor.

It is notable that the Dubliners in the Burton are frequently described in bovine terms. Bloom opens with the line “see the animals feed” and remarks at one of the men “chewing his cud.” Their lunchtime meal ultimately evokes images of bloody slaughter in the cattlemarket where Bloom used to work:

“Hot fresh blood they prescribe for decline. Blood always needed. Insidious. Lick it up smokinghot, thick sugary. Famished ghosts.”

The spectacle of the men in the Burton is not just due to their impropriety, but the fact that they look and behave this way because of inescapable poverty. Bloom is experiencing class horror. Being able to sit down and eat slowly and daintily as Bloom ultimately does is due the fact that the demands of his work are light that day. Yes, Bloom needs to secure the ad from Keyes, but he more or less makes his own schedule. He doesn’t have a boss imposing a strict and likely too-short lunch period on him. Indulging in a long lunch doesn’t put him in danger of losing his livelihood. Bloom is by no means a wealthy man, but while he is conscious of his expenditures, he is not stressed about the prices of his meals in any meaningful way. He eats according to his tastes, not his pocketbook or his master’s schedule.

The men in the Burton, by contrast, are perhaps wolfing down their meals because they don’t have time to be polite and tidy. They’ve chosen a cheap, protein-rich meal that allows them to return to their labor. The scene is ugly because the economic conditions that make this sort of lunch necessary are ugly. On the surface, we see the violence of the men’s method of consumption, but they are ultimately the victims of the violence of poverty. Their blood and bodies are requisite for the maintenance of the economic system. The rich men making their money off their labor and sacrifice are the “famished ghosts,” always requiring more and more blood. Like the cattle slaughtered for profit, they are ground up and devoured by the habits of wealthy men. The captains of industry and commerce may well be haunted through all eternity by the eyes of the men they exploited. While we can easily interpret these men as the cannibalistic horde, when we take their economic situation into consideration, Dublin’s middle and upper classes become the Lestrygonians, gobbling up the bodies of laborers without regard for their humanity.

The aftermath of the Easter Rising

To expand this interpretation, we must consider the nightmare of history. How many of these men will be mown down in the wars of the early 20th century? How many of their children will go hungry during the Lockout in 1913? Will they, or others like them, end up in the trenches on the Western Front fighting for the Empire? Or will they die fighting for Ireland in 1916 or the Irish Civil War? Given the circumstances of their birth, few of them are likely to live a quiet life in a leafy suburb. “Lestrygonians” was written in 1918, two years after the Easter Rising and the Battle of the Somme, during the final year of World War I. Joyce and his family were living in Zürich that year, having fled Trieste due to the War in 1915, the same year his brother Stanislaus was imprisoned for his political views.

Writing in Flashpoint Magazine, Rod Rosenquist sees a direct parallel to how different diets portrayed in Ulysses correspond to the Irish political movements of the 1910’s. He notes that violence of the Burton men alludes to the “rhetoric of blood” of Easter Rising leader Padraic Pearse, who wrote in 1913:

“We may make mistakes in the beginning and shoot the wrong people; but bloodshed is a cleansing and satisfying thing, and the nation which regards it as the final horror has lost its manhood. There are many things more horrible than bloodshed; and slavery is one of them.”

Rosenquist sees the phrase “famished ghosts” as a reference to Pearse’ pamphlet entitled “Ghosts”, which played a role in the lead up to the 1916 Rising. Joyce felt great ambivalence to Pearse’s words. While Joyce certainly opposed the “slavery” that societal malaise imposed on Ireland due to British colonialism, his work emphasizes the narrow-mindedness of nationalism, no matter which country it supported. Joyce felt uneasy about the Easter Rising and, like his most famous literary creation, opposed political violence more generally. Joyce knew Pearse when he still lived in Dublin, but I don’t think he embraced the politics of Pearse. In addition to calls for blood in this extract, Pearse’s appeal to masculinity is notable. Joyce described Bloom as a “womanly man”, a term he also applied to himself. This bloody, violent masculinity alienated Joyce and, by extension, Bloom.

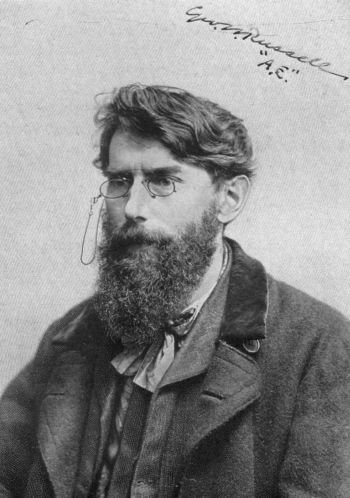

Æ

At the other end of the spectrum from manly, bloody insurrection lies Æ, vegetarian, Irish nationalist, and opponent of political violence. Bloom clocks Æ on the street and conjectures about his vegetarian lunch at a nearby restaurant. (You can read our blog post about it here). Bloom imagines vegetarians like Æ as being lost in the clouds and out of touch with the normal patterns of life. Æ is peaceful, reminiscent of the lotus eaters, and a soft, feminine man. Æ shared Pearse’s nationalistic politics and dedicated himself to securing a better quality of life for people in rural Ireland. However, Æ was shocked by the Rising and used his influence to urge compromise as his country edged toward civil war in the early 1920’s. Æ’s vision for an independent Ireland was similar to Canada, free enough to chart its own course but still tethered to Britain. This proposal was not well received as it satisfied no one and led ultimately to the decline of Æ’s political influence as his friends, including W.B. Yeats and Oliver St. Gogarty, took up roles in the newly formed Seanad. Passivity has already failed Bloom, as we saw at the beginning of this sequence.

Rosenquist describes this conflict between lestrygonian cannibals and lotus eating pacifists as Bloom’s personal Scylla and Charybdis moment, leaving him caught between a rock and a hard place. When faced with such an unappealing binary, one must find a third option or risk going hungry, which is where we leave Bloom at the end of his ordeal:

“Ah, I’m hungry.”

Further Reading:

Adkins, P. (2017). The Eyes of That Cow: Eating Animals and Theorizing Vegetarianism in James Joyce’s Ulysses. Humanities, 6 (46). Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0787/6/3/46

Budgen, F. (1972). James Joyce and the making of Ulysses, and other writings. London: Oxford University Press. Retrieved from https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AMF2PZFZHI2WND8U

Freedman, A. (2009). Don’t eat a beef steak": Joyce and the Pythagoreans. Texas Studies in Literature and Language, 51(4), 447–462. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40755555

Kain, R., & O’Brien, J. (1976). George Russell (A.E.) London: Associated University Presses.

Osteen, M. (1995). The economy of Ulysses: making both ends meet. New York: Syracuse University Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yycf2ar5

RICH, L. (2010). A Table for One: Hunger and Unhomeliness in Joyce’s Public Eateries. Joyce Studies Annual, 71–98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26288755

Romanoff, A. Lestrygonians-Modernism Lab. Retrieved from https://campuspress.yale.edu/modernismlab/lestrygonians/

Rosenquist, R. Bloom’s digestion of the economic and political situation. Flashpoint Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.flashpointmag.com/lestrgon.htm

Tucker, L. (1984) Stephen and Bloom at Life’s Feast. Ohio State University Press.

WILLIAMS, T. L. (1993). “Hungry man is an angry man”: A Marxist Reading of Consumption in Joyce’s “Ulysses.” Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature, 26(1), 87–108. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24780518

Yared, A. (2009). Eating and Digesting “Lestrygonians”: A Physiological Model of Reading. James Joyce Quarterly, 46(3/4), 469–479. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20789623