Agendath Netaim

To listen to a discussion of this topic, check out the podcast episode here.

“He took a page up from the pile of cut sheets: the model farm at Kinnereth on the lakeshore of Tiberias. Can become ideal winter sanatorium. Moses Montefiore. I thought he was. Farmhouse, wall round it, blurred cattle cropping. He held the page from him: interesting: read it nearer, the title, the blurred cropping cattle, the page rustling.”

The cited passages appear mainly on pgs. 59-60 of Ulysses (1990 Vintage International Edition).

Sometimes all a man needs is a nice pork kidney to start his day.

Leopold Bloom is endeavoring to do just this in “Calypso,” Ulysses’ fourth episode. Our hero has nipped around the corner from his house to buy the last pork kidney from Mr. Dlugacz, a porkbutcher and fellow Hungarian Jew. This encounter highlights just how tepid Bloom’s Judaism is - he’s opting for a decidedly un-kosher breakfast treat while ogling the “moving hams” of a stout cleaning woman. To reign in his lust while waiting in line, Bloom picks up a pamphlet for Agendath Netaim, a Zionist “planter’s company” offering to sell plots of land in Palestine to be planted with citrus trees and other crops. The Zionist movement encouraged the Jewish diaspora to settle in Palestine in order to create a Jewish homeland, eventually (spoiler alert) culminating in the foundation of the state of Israel in 1948. Bloom reads the pamphlet with interest, but given the casual nature of his Judaism, does it stir a longing in him for a Promised Land far to the East?

“He walked back along Dorset street, reading gravely. Agendath Netaim: planters' company.”

To begin with, Agendath Netaim was a real company, or real enough for our purposes. In Hebrew, the name means “plantation company,” rather than “planter’s company” as Bloom renders it. We can assume the non-observant Bloom’s Hebrew is less than perfect. As it turns out, so was James Joyce’s. The company’s actual name was “Agudat Netaim.” It’s unclear why the name ended up as “Agendath” in the text of Ulysses, but don’t worry, scholars have so many theories.

The discrepancy might have been a simple typographical or transcription error - “u” and “en” look a bit similar in Joyce’s cursive handwriting. Or maybe he just wrote it down incorrectly, not being well-versed in Hebrew. It was then never picked up in successive rounds of editing since the editors were also not Hebrew readers. Maybe. Some think it may have been changed purposely to look like “agenda,” hinting at Agendath Netaim’s political agenda. Bloom later remembers the name as “Agenda what was it?” The spelling could also hint at “Uganda,” which was once proposed as a potential Jewish homeland. Francis Bulhof thought that it was altered in order to map onto Stephen’s “Agenbite of Inwit” to show the beginnings of the gradual merging of Stephen and Bloom’s consciousnesses in a Ulyssean hypostasis. Perhaps. There’s no consensus to date, so feel free to adopt the theory you like best.

“To purchase vast sandy tracts from Turkish government...”

Agudat Netaim, then, was the real company. Founded in 1905 by Aharon Eisenberg, the company aimed to build a Jewish colony near the Sea of Galilee (aka Lake Tiberias). Because the art of “Calypso” is economics, let’s take a moment to consider Eisenberg’s business plan. His company would buy plots of land, turn them into plantations, and resell them for a profit. A key part of Eisenberg’s strategy was that the company trained middle-class European Jews to be plantation farmers, hopefully increasing the plantation’s profitability and the likelihood that the farmers would make Palestine their home. Agudat Netaim was the largest capitalist organization during the period of Jewish emigration to Palestine from 1904 to 1914, though they were less successful as a colonizing enterprise. The region was under control of the Ottoman Empire which, reluctant to sell land to Jewish colonists, placed many restrictions on world-be planters. Nevertheless, Agudat Netaim carried on and by 1914 employed around 20% of Eastern European Jewish laborers in Palestine.

If you’re paying close attention, you might have noticed that Agudat Netaim wouldn’t have existed at all in 1904, making it impossible that Mr. Bloom could peruse a copy of their prospectus. No worries. While Joyce did incorporate many precise details about 1904 Dublin in Ulysses, he was also pretty flexible with facts when it suited him. If Mr. Deasy is on his way to a meeting about an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease that wouldn’t affect real-life Dublin until 1912, then Mr. Bloom can read a pamphlet from a company that wouldn’t exist for another year.

“Every year you get a sending of the crop. Your name entered for life as owner in the book of the union. Can pay ten down and the balance in yearly instalments. Bleibtreustrasse 34, Berlin, W. 15.”

Agendath Netaim’s address at Bleibtreustraße 34 in Berlin is another piece in our puzzle. The German phrase “bleib treu” translates to “stay faithful.” So, is this Zionist planter’s company located on Stay Faithful Street? Is Bloom rejecting the call of Zion because he’s estranged from his faith? Is it a subtle mockery as Bloom has just purchased a most un-Kosher pork kidney? Bleibtreustraße exists in real-life Berlin, taking its name from the German artist Georg Bleibtreu, though this particular address didn’t exist until 1908 when the building was built. Additionally, Joyce met Bleibtreu’s son Karl in Zurich in 1917 and mentions him as “Herr Bleibtreu” in “Scylla and Charybdis.” While locating a Zionist planter’s company on Stay Faithful Street is thematically resonant, it wasn’t the product of Joyce’s imagination.

While Agudat Netaim never made its home at Bleibtreustraße 34, the address was used by groups including the Palestine Real Estate Corporation, the Tiberias Land and Plantation Corporation, and the Palestine Land Development Company (PLDC). The third company still exists today under the name Israel Land Development Company. Historically, they have been one of the most successful groups in the business of buying land in Palestine for Jewish resettlement.

To return to our art of economics, the PLDC’s innovative plan allowed buyers of more modest means to put down a down payment on a property and then pay off the remainder in monthly installments. The system was so novel to Europeans in the early 1900’s that it was nicknamed the “California plan.” The PLDC’s plan worked in part because it allowed middle class buyers to circumvent the enormous fees imposed by the Turkish government on Jewish-bought properties as they no longer had to present all the money up front. There doesn’t seem to be any further historic connection between the PLDC and Agudat Netaim, apart from a common goal of a Jewish colony in Palestine. Agudat Netaim and the PLDC were big players in Palestine at the time, and it seems Joyce took the name of one and grafted it onto the address of another to create a fictional-but-somewhat-real company for Bloom to ponder throughout his day.

From James Joyce Quarterly

“He took a page up from the pile of cut sheets: the model farm at Kinnereth on the lakeshore of Tiberias. Can become ideal winter sanatorium. Moses Montefiore. I thought he was. Farmhouse, wall round it, blurred cattle cropping.… Orangegroves and immense melonfields north of Jaffa.”

Kinnereth, on the shore of the Sea of Galilee/ Lake Tiberias, was settled in the early 1900’s (though after 1904). Rather than being a “model farm,” Kinnereth was a moshava, or a rural Jewish settlement, that included a farm used to train would-be farmers. The area also contained hot springs and mineral baths which could indeed make for a nice winter sanatorium. Moses Montefiore was a Jewish philanthropist who used his wealth to support Zionist projects in Palestine during the 19th century, including planting a citrus grove northeast of Jaffa (in modern day Tel Aviv). Montefiore’s grove is now the Tel Aviv suburb of Shekhunat Montefiore. Kinnereth and Galilee are also northeast of Jaffa. In the area around Kinnereth, the two main Jewish agricultural activities were citrus farms and cattle.

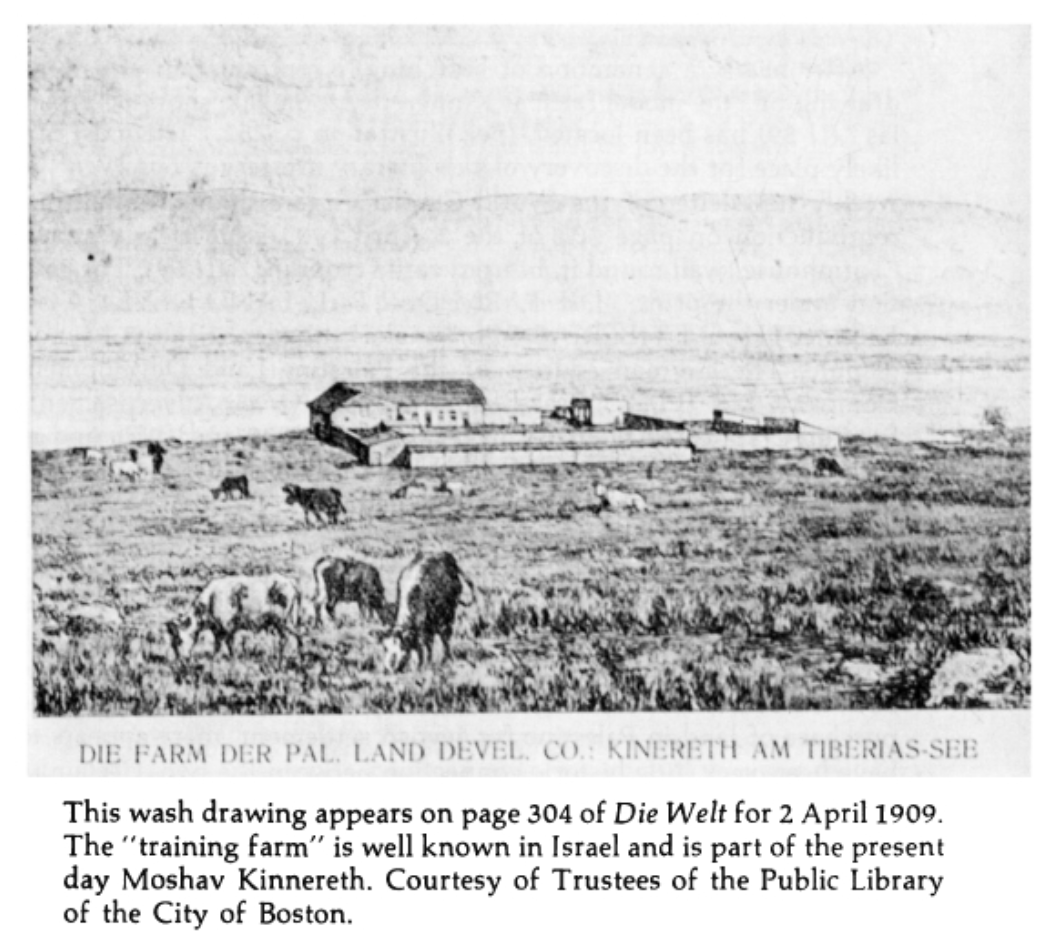

The description Bloom gives here, “Farmhouse, wall round it, blurred cattle cropping,” accurately describes an image that appeared in Die Welt, the weekly newsletter of the World Zionist Organization on April 2, 1909. During this same time, the PLDC was operating out of Bleibtreustraße 34, whose ads ran regularly in Die Welt, bearing that same Berlin address. As these details fall into place, we can assume that Joyce had access to a copy of Die Welt from this time period. The images used in this post were taken from this article in James Joyce Quarterly.

The model farm at Kinnereth, from James Joyce Quarterly

“I thought he was…. A speck of eager fire from foxeyes thanked him. He withdrew his gaze after an instant. No: better not: another time.”

We can make an educated guess that Joyce was familiar with Zionist literature, though he likely first encountered it after he had already left Dublin. One clue is that many of the Zionist activities Joyce is detailing in “Calypso” date, in reality, from the late 1900’s after he had already made his own exodus from Ireland. While living in Trieste, Italy, Joyce worked as an English tutor and befriended several Jewish students who would become immensely influential over his artistic work, such as Ettore Schmitz (Italo Svevo) and Leopoldo Popper. Another of his students was Moses Dlugacz, an ordained rabbi from a family of Ukrainian rabbis and a founder of a Hebrew language class in Trieste. He was also a passionate Zionist, eventually emigrating to Palestine himself. Though Joyce knew several of the professional, European Jewish families that companies like Agudat Netaim were hoping to court, it seems likely that Dlugacz was his source of information on Zionism.

It’s no coincidence, then, that Bloom finds the prospectus for Agendath Netaim while waiting to buy his kidney from Dlugacz, “the ferreteyed porkbutcher.” Dlugacz’s profession might seem out of step for a Jewish man, but it was not uncommon in that time period for Jewish butchers to cater to Gentiles as well. As Neil R. Davison wrote, “...immigration and economics make strange bed-fellows, and kosher butchers didn’t do too well in Dublin.” We can assume that Dlugacz is more in touch with his Judaism than Bloom because he is receiving mail from the PLDC at Bleibtreustraße 34. The line, “I thought he was,” shows us that Bloom suspected Dlugacz was a Zionist. Dlugacz’s “ferreteyes” become “foxeyes” the moment Bloom thinks of asking about Agendath Netaim. Is that “spark of eager fire” a Zionist ember or is it something else? “No: better not: another time,” Bloom decides not to ask, and so we’ll never know.

Moses Montefiore on an Israeli 10 pound note

Mr. Dlugacz’s “foxeyes” stand out as well because they are potentially a connection to disgraced Irish politician Charles Stewart Parnell. Famous both for fighting for Irish devolution and being brought low by a sex scandal, Joyce, in his essay “The Shade of Parnell,” described how Parnell “like Moses, lead a turbulent and unstable people from the house of shame to the verge of the Promised Land.” Parnell’s “code name” while communicating with his lover was “Mr. Fox,” and I read one source that said that any time a fox is mentioned in Ulysses, it’s an oblique reference to Parnell. I don’t know if it means anything, but a sort-of Moses with “foxeyes” is too intriguing to just ignore.

As a Homeric parallel, Dlugacz stands in for the god Hermes, who traveled at the behest of Zeus to Ogygia to demand Odysseus’ release from Calypso’s cave. Dlugacz is subtly calling Bloom “home” to Zion, but Bloom, unlike Odysseus, does not heed the call. Later on page 68, Bloom thinks again of the porkbutcher, “Deep voice that fellow Dlugacz has. Agenda what was it? Now, my miss. Enthusiast.” Bloom is unsure that his Hermes figure would deliver him to the Promised Land. Instead, he may be a mere enthusiast, happy to leave a pamphlet in a strategic location but not likely to take real action.

“Nothing doing. Still an idea behind it.”

In the end, does Bloom accept or reject the call of Zion in the East? Bloom’s summative thought on the pamphlet rejects Agendath Netaim (“Nothing doing”) but doesn’t totally close the door to future possibility (“Still an idea behind it”). The phrase “Agendath Netaim” is Ulysses’ most-repeated catchphrase, appearing around a dozen times, more than either “Agenbite of Inwit” or “Elijah is Coming.” Even if Bloom isn’t currently planning to build Bloomville in Palestine, the idea resonates enough to stick in his mind on June sixteenth.

No, not like that. A barren land, bare waste. Vulcanic lake, the dead sea: no fish, weedless, sunk deep in the earth. No wind could lift those waves, grey metal, poisonous foggy waters.

A cloud begins to obscure the sun, and Bloom’s daydream of “vast sandy tracts” shifts suddenly into a desiccated husk of a wasteland, his would-be Zion symbolized by “a bent hag [crossing] from Cassidy's, clutching a naggin bottle by the neck.” The Agendath Netaim pamphlet makes would-be buyers some high-flying promises, but upon closer inspection, cracks appear.

Kinneret on the lakeshore of Tiberias

Consider the economics of this proposal: “To purchase vast sandy tracts from Turkish government and plant with eucalyptus trees. Excellent for shade, fuel and construction.” How are you going to make your money back on your plantation investment selling shade and firewood? On top of that, the land around the Sea of Galilee isn’t particularly dry or sandy. Rather, planting eucalyptus trees was encouraged to dry out the marshy soil in order to drive out malaria-carrying mosquitoes and make this region of Palestine habitable. If selling shade and battling malaria didn’t dissuade you as an investor, political instability might. Once the Ottomans (aka the Sick Man of Europe) had fallen, the Young Turks, who took power after their revolution in 1908, were hostile toward foreign land buyers, Zionist or not.

Joyce felt that Zionism was an impractical project, more an exercise in dream-chasing than nation-building, a passing enthusiasm. There is an idealism and an optimism to the Zionist mindset of men like Moses Montefiore: European Jews experienced terrible persecution in 19th century Europe, such as pogroms, high rates of poverty and unemployment, and political and legal discrimination such as the Dreyfus Affair. Creating a Jewish homeland far from Europe offered a way out, a new beginning. It’s not hard to see why an Exodus from Europe made sense. However, Joyce presents Agendath Netaim’s goals as purely commercial, capitalist and profit-oriented. It’s possible that there was an ideological or political pitch in their prospectus as well, though it doesn't appear in the text of Ulysses. Maybe Bloom wasn’t interested in that section as he skimmed the pamphlet while waiting for his kidney. His mind is focused on economics, and it seems Joyce wanted to highlight the economic angle of Agendath Netaim’s enterprise over any hypothetical ideals.

There was plenty of skepticism toward Zionism amongst European Jews during this era. Some Orthodox Jews felt that political Zionism was actually blasphemous, as it was God’s work to send a Messiah to reclaim Zion, not the work of mortal men. Assimilated Jews also held doubts. Not only was settling in Ottoman Turkish lands a difficult proposition, there were already around 600,000 Muslims and Christians living in Palestine. It wasn’t clear the land could support a large influx of settlers and financial backing was hard to come by for large-scale settlement. The ongoing conflict between modern-day Israelis and Palestinians proves how contentious such a project truly is.

Nationalistic politics in general rankled Joyce. When asked if he would be willing to die for Ireland, Joyce replied, “I say let Ireland die for me.” He tended to see yearning for the long-lost past, whether it be the Israel of King David or the Heroic Ireland celebrated by poets like W. B. Yeats and Lady Gregory, as nothing but a desire to enter a fantasy land. Think of Stephen Dedalus recalling his absinthe-soaked conversations with Kevin Egan, exiled Fenian, in “Proteus”: “Weak wasting hand on mine. They have forgotten Kevin Egan, not he them. Remembering thee, O Sion.” Dreaming of Zion (Sion) is for men trapped in toxic nostalgia. You may yearn for the past, but the past yearns not for you.

Zionism is such a powerful motif in Ulysses because at its heart, it is the story of man trying to go home and not being certain where that home is. Is Bloom Odysseus, trying to find peace in his own private Ithaca at 7 Eccles St., or is he perhaps a modern-day Moses, wandering for nearly 40 years in a wilderness in search of his land of milk and honey, far to the East?

By ignoring the call in Dlugacz’s butcher shop, Bloom chooses to be Odysseus. Edwin Williams wrote that Bloom, in the end, chooses Molly over some kind of fantastical Eastern promise, “Fantasy, art, dreams can become a substitute for reality…. As long as he entertains the prospect of escape to a fertile land in the East, he is incapable of being a true husband to Molly.” Following his escapades with Stephen in Nighttown, Bloom ultimately burns the Agendath Netaim pamphlet in order to light some incense, its flame transforming the cone of incense into “a vertical and serpentine flume redolent of aromatic oriental incense.” To find his lost home, our Odysseus must learn to “stay faithful” not to a dream, but to his real queen. He must choose the lemon soap and creamfruit melons of home over the citrus trees and vast tracts of melonfields in Zion.

Further Reading:

Bell, M. (1975). The Search for Agendath Netaim: Some Progress, but No Solution. James Joyce Quarterly,12(3), 251-258. Retrieved February 28, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/25487184

Bulhof, F. (1970). Agendath Again. James Joyce Quarterly,7(4), 326-332. Retrieved March 4, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/25486859

Byrnes, R. (1992). Agendath Netaim Discovered: Why Bloom Isn't a Zionist. James Joyce Quarterly,29(4), 833-838. Retrieved February 11, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/25485325

Davison, N. R. (1998). James Joyce, Ulysses, and the Construction of Jewish Identity: Culture, Biography and ‘the Jew’ in Modernist Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/rp9ctrt

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/vy6j4tk

McNally, F. (2020, Feb 28). How Joyce paid the ferryman. The Irish Times. Retrieved from https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/how-joyce-paid-the-ferryman-1.4187092

Parish, C. (1969). Agenbite of Agendath Netaim. James Joyce Quarterly,6(3), 237-241. Retrieved February 22, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/25486772

Philologos. (2018, Jun 27). The real zionist planters' society in James Joyce's "Ulysses." Mosaic. Retrieved from https://mosaicmagazine.com/observation/israel-zionism/2018/06/the-real-zionist-planters-society-in-james-joyces-ulysses/

Shafir, G. (1996). Land, Labor and the Origins of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, 1882-1914. Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/texbal9

Wicht, W. (2003). "Bleibtreustrasse 34, Berlin, W. 15." (U 4.199), Once Again. James Joyce Quarterly,40(4), 797-810. Retrieved March 14, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/25477995

Williams, E. (1986). Agendath Netaim: Promised land or waste land. Modern Fiction Studies,32(2), 228-235. Retrieved February 22, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/26281745

Source for image of Kinneret