Decoding Dedalus: Latin Quarter Hat

He dressed in black, a Hamlet without a wicked uncle…. - Richard Ellmann

This is a post in a series called Decoding Dedalus where I take a passage of Ulysses and break it down line by line.The passage below comes from “Proteus,” the third episode of Ulysses. It appears on pages 41-42 in my copy (1990 Vintage International). We’ll be looking at the passage that begins “My Latin quarter hat.” and ends “...curled conquistadores.”

To listen to a discussion of this topic, check out the podcast episode here.

In December 1901, a young, determined James Joyce showed up in Paris to study medicine. There were other, more sensible courses of study he could have taken. Most obviously, he could have carried on at University College Dublin where he had done his undergraduate work. However, he couldn’t afford the fees, and the university had denied him work doing grinds (tutoring), which would have helped him earn money to pay his fees. There was no particularly compelling reason for Joyce to study medicine in Paris. In fact, he had some powerful connections (W.B. Yeats, Lady Gregory) who were more than happy to call in favors and get him a position in Dublin or London as a writer. But no, Paris was the only option. He wrote to Lady Gregory that he would travel to Paris “alone and friendless,” that he must “try [himself] against the powers of the world.”

Richard Ellmann wrote that Joyce was provisionally allowed entrance into the École de Médecine at La Sorbonne, despite the fact that the term was mere weeks from ending. Joyce’s younger brother Stanislaus, on the other hand, said that when his brother arrived in Paris, the university didn’t recognize his undergrad degree from Ireland and that he would have had to pay all of his student fees in advance of study, still an issue for the Young Artist. Apparently, this information could have been ascertained while Joyce was still in Dublin. It was also not clear if a French medical degree would be valid in Ireland or if Joyce intended to practice medicine in France. Such setbacks would not turn our intrepid hero aside, however. He remained in Paris, as Stanislaus tells it, “with some undefined purpose, vaguely literary.”

In this passage, Stephen remembers his days in Paris as he strolls along the strand.

My Latin quarter hat. God, we simply must dress the character. I want puce gloves.

Stephen Dedalus and James Joyce both tried desperately to become a bohemian artist during their time in Paris. Simply traveling to Paris does not a bohemian make, however. So what’s a young Artist to do? Fake it til you make it, as they say. Stephen employed a fashion-first method of transforming into a bohemian writer. He adopted a Parisian style of dress, a style he was still clinging to upon his return to Dublin. There is a photo of Young Joyce in December of 1902 dressed in what Ellmann described as “a heavy, ill-fitting coat and a long-suffering look.” A bit harsh. Young Joyce looks good in my opinion, if perhaps a little emo. You can judge for yourself in the photo on the left, below.

While Joyce’s fashion critic manifested in his biographer, Stephen’s inner-critic manifests in the voice of Buck Mulligan. Back in “Telemachus,” Buck Mulligan teased Stephen about his “Latin Quarter hat,” not long after he teased Stephen about his fussy Parisian habit of taking his tea with lemon rather than good Sandycove milk like a proper Irishman. Mulligan may be a pain in the ass, but he sees that his old friend’s behavior is inauthentic and jejune. Stephen is wearing a costume, trying to pretend that he is someone else. Stephen, in his mind, dressed Mulligan in the “puce gloves” that make their second appearance here. Stephen may be in a costume, but so is Mulligan. Mulligan is clothed in his own brashness and crudity, of which the snotgreen gloves are an outward symbol.

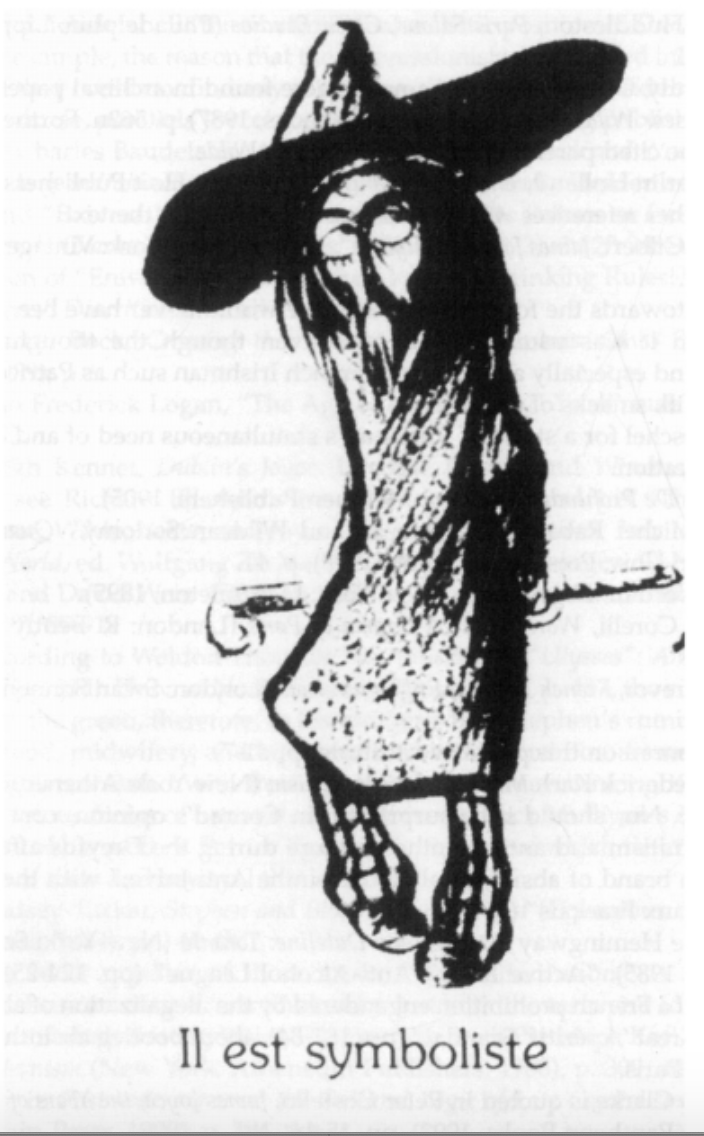

In real-life, Oliver St. John Gogarty, Mulligan’s real-life counterpart, said that Joyce was trying to ape the style of French symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud. Based on the center sketch below by the poet Paul Verlaine, he may have been on to something. David M. Earle noted a cartoon sketch (on the right, below) of “un symboliste” that was drawn in 1901 showing a young, shaggy-bearded man in dark clothing, wearing a black, wide-brimmed hat and carrying an ashplant. Stephen/Joyce is absolutely “dressing the character.”

You were a student, weren't you? Of what in the other devil's name? Paysayenn. P. C. N., you know: physiques, chimiques et naturelles. Aha.

“Paysayenn” is the phonetic pronunciation of the way the letters “PCN” are pronounced in French. They stand for the three subjects listed here in French, which are physics, chemistry and biology (sciences naturelles). Ellmann thought that one reason Joyce didn’t get very far in his medical studies was that he had barely passed chemistry in Dublin and was unlikely to have had better success in a second language.

Eating your groatsworth of mou en civet, fleshpots of Egypt, elbowed by belching cabmen.

Because of the half-baked nature of Young Joyce’s plan to run away to Paris, he found himself in fairly dire poverty. He regularly wired his family for more money, and his mother would wire back a few shillings when she could. Days at a time would sometimes pass where he didn’t eat at all. Joyce believed he could make enough money teaching English and writing reviews to make ends meet. He was offered a full-time gig at a Berlitz language school at one point, but turned it down for fear it would interfere with his writing. As if starving wouldn’t interfere as well.

Here, Stephen thinks about eating “mou en civet.” A “civet” is a stew or sauce made from wild game, often rabbits. Mou means lung. So, lung stew. Not exactly haute cuisine, costing him a groat when he scrape one up. The “fleshpots of Egypt” is reference to Exodus 16:3 in the King James version of the Bible, where the Israelites are wandering in the wilderness, reminiscing about how much better life was back in Egypt. Sure they were enslaved, but they had bread and flesh pots, which I’m assuming are pots with some form of meat inside. That lung stew starts looking pretty good after wandering in the desert.

Just say in the most natural tone: when I was in Paris; boul' Mich', I used to.

The next step to convincing the folks back home you’ve become a sophisticated Parisian: speaking the part. Dropping bits of French into your daily conversation (plenty of that in “Proteus”). “Boul’ Mich’” is a slangy name for the Boulevard St. Michel, a major thoroughfare in the Latin Quarter of Paris.

Yes, used to carry punched tickets to prove an alibi if they arrested you for murder somewhere. Justice. On the night of the seventeenth of February 1904 the prisoner was seen by two witnesses. Other fellow did it: other me. Hat, tie, overcoat, nose. Lui, c'est moi. You seem to have enjoyed yourself.

Carrying around old fare tickets as an alibi seems to have been a peculiar habit of Stephen’s, possibly revealing a bit of paranoia on his part. On 19 February 1904, the Irish Times reported on the death of Teresa McCarthy, who had been murdered by her abusive husband. It was the sad end to a long history of abuse, to which two witnesses testified. I’m not sure why Stephen would reflect on this crime specifically. It doesn’t fit the timeline of his Paris sojourn. However, one hideous detail from the Irish Times article revealed that Teresa had previously miscarried because of the abuse. She was almost a mother, and she too had died.

“Lui, c’est moi,” meaning “I am him,” is a play on “L'état, c'est moi,” as spoken by King Louis XIV, meaning “I am the state.” Somehow he wasn’t the king who got his head chopped off.

Proudly walking. Whom were you trying to walk like? Forget: a dispossessed.

Stephen’s feelings of imposture peek through.

With mother's money order, eight shillings, the banging door of the post office slammed in your face by the usher. Hunger toothache. Encore deux minutes. Look clock. Must get. Ferme. Hired dog! Shoot him to bloody bits with a bang shotgun, bits man spattered walls all brass buttons. Bits all khrrrrklak in place clack back. Not hurt? O, that's all right. Shake hands. See what I meant, see? O, that's all right. Shake a shake. O, that's all only all right.

One way Stephen/Joyce sustained himself financially in Paris was wiring his mother to ask for money, which she provided whenever she could, even if it meant selling the family’s possessions to support him. In Joyce’s case, this included funding a trip back to Ireland for Christmas a few weeks after arriving in France. Here, Stephen tries desperately to cash a money order, which might be the only thing allowing him to eat his lung stew that night. There are two minutes until close (Encore deux minutes!), but the worker slams the door in Stephen’s face.

During the early months of 1902, Joyce suffered a toothache, but didn’t have the money to visit a dentist. More hardship on top of the persistent hunger. Notice the quick, flashing fantasy of blowing the postal worker to bits. It’s all in Stephen’s head, a quick burst of blind rage, but no action taken. If you remember the HBO show Six Feet Under, this bit reminds me of the way characters on that show would commit violent or absurd actions, only to flash back to the “normal” story, revealing that the other timeline was just a fantasy. I suppose it’s normal human behavior to imagine violence after having a door unjustly slammed in one’s face.

Joseph Heininger points out that this shows Stephen as “ a revolutionary of the trivial” - an artistic dilettante whose political world view is just as underdeveloped. Stephen has clothed himself in the costume of a worldly young man, but in reality his rage is not channeled into his art but instead onto fussy postal clerks. In the end, Stephen is easily placated. I can also see this as the rage of a young man who is increasingly aware of his own powerlessness. This incident is creeping back into his thoughts here on Sandymount as a stand-in for the desperation brought on by his current poverty.

You were going to do wonders, what? Missionary to Europe after fiery Columbanus. Fiacre and Scotus on their creepystools in heaven spilt from their pintpots, loudlatinlaughing: Euge! Euge!

Even though his motives were murky to his friends, brother and biographer, Joyce/Stephen had high hopes for his time in Paris. He was thoroughly convinced of his own genius but just needed to find a testing ground. Stephen imagined himself like St. Columbanus, an Irish saint who earned fame by traveling to France. St. Fiacre (patron saint of gardeners, herbalists and sufferers of hemorrhoids and venereal disease) did likewise, as did John Duns Scotus (though he is claimed by Ireland, Scotland and England). Really, the biggest thing these men have in common is leaving Ireland on a faith-based mission for France. Stephen imagines St. Fiacre and Duns Scotus in heaven laughing at him and mocking him in Latin. “Euge!” can mean “applause” or “hurrah!”

Pretending to speak broken English as you dragged your valise, porter threepence, across the slimy pier at Newhaven. Comment?

Upon his return to Dublin, Joyce was penniless. He pretended to not speak English at the crossing into England to avoid tipping the porter.

Rich booty you brought back; Le Tutu, five tattered numbers of Pantalon Blanc et Culotte Rouge;

Culotte Rouge

All Stephen accomplished in his Parisian sojourn was amassing a small collection of cheap French pornography.

a blue French telegram, curiosity to show:

—Mother dying come home father.

This phrase was the entire content of the telegram Joyce’s father sent to tell him of his mother’s terminal illness. He needed to make the crossing back to Ireland immediately, but of course, had no money. In the middle of the night Joyce showed up at the flat of a wealthy wine merchant, M. Douce, who he was tutoring in English, showed him the telegram and borrowed the fare money. Stanislaus is quick to point out that his brother made sure M. Douce was paid back in full.

The aunt thinks you killed your mother. That's why she won't.

More echoes of Mulligan. He’s set up a little camp in Stephen’s subconscious and won’t let him have a minute alone.

Then here's a health to Mulligan's aunt

And I'll tell you the reason why.

She always kept things decent in

The Hannigan famileye.

A slight reworking of the lyrics to the song “Matthew Hanigan’s Aunt” by Percy French.

Paris rawly waking, crude sunlight on her lemon streets. Moist pith of farls of bread…

Some lovely imagery here of Paris waking up in this paragraph. I recommend listening to this song while you read it.

...the froggreen wormwood…

In Stuart Gilbert’s schema, green is the color correspondent with the “Proteus” episode. Back in “Telemachus,” Buck Mulligan celebrated the color green:

-The bard’s noserag! A new art colour for our Irish poets: snotgreen. You can almost taste it, can’t you?

Here we see green, however disgustingly, associated with creative production, with Irish poets and with the sense of taste. So green you can taste it. Ineluctable modality of the gustatory. The distinctive green of absinthe had become a symbol, a stereotype really, of the bohemian French poet by 1902. The green of absinthe was the new art color indeed, as many artists, the French Symbolists in particular, saw intoxication as central to achieving new perceptions. Intoxication offended the bourgeoisie, therefore it was the only way to transcend their conservativism. Stephen clearly wanted to embody just such a bohemian model in his Parisian sojourn. Of course, for Stephen green also has the context of a grimmer production, in the form of the phlegm coughed up by his dying mother.

...her matin incense, court the air.

Stephen encountered the ineluctable modality of the olfactory in the early morning air of Paris. The fresh bread of the boulangeries, last night’s inspiring, intoxicating liquor of the artists, and the incense of the pious. Matins, now called the Office of Readings, is part of the Liturgy of the Hours in the Catholic Church. Basically, these are services held in Catholic churches at key hours of each day, but are not a full Masses. Matins (“matin” is the French word for “morning”) takes place in the wee hours of the morning, perhaps around 2 AM. The idea is that you get out of bed to attend this service, between Compline (just before bed) and Lauds (first thing in the morning). Catholicism is hard AF.

Since the sun is above the horizon, these scents are lingering in the air, rather than occur as Stephen walks by. I find this image pleasingly Berkeleyan, since the shapes of these objects and experiences are sketched in Stephen’s mind through his sense of smell. He can’t be sure of their true form since he is only coming into contact with them via his nose.

Belluomo rises from the bed of his wife's lover's wife, the kerchiefed housewife is astir, a saucer of acetic acid in her hand.

Church incense isn’t the only thing rising early in the morning. “Belluomo” means a handsome man or prankster in Italian. I guess the prank here is complex non-monogamy.

The saucer of acetic acid, a key component in vinegar, is likely used for household cleaning. Possibly to clean up the stains, physical and moral, of some other belluomo. Maybe before the housewife’s husband gets home.

In Rodot's…

A patisserie on Boul’ Mich’.

Yvonne and Madeleine newmake their tumbled beauties, shattering with gold teeth chaussons of pastry, their mouths yellowed with the pus of flan breton. Faces of Paris men go by, their wellpleased pleasers, curled conquistadores.

Gold teeth, reminding us of golden-mouthed Buck Mulligan on the Tower giving Mass. Yvonne and Madeleine are enjoying pastries called chaussons, which are similar to turnovers. “Chausson” comes from the French for slipper, bootie or ballet slipper.

They’ve already been at the flan breton, another pastry. It’s not the custardy flan that you might be familiar with (that’s called crème caramel in French). Instead, it’s an egg-and-milk-based pastry from Brittany, similar to a clafoutis. It’s often referred to as “far breton” because “far” is the Breton word for “flan.” People from Brittany (Bretons) have a culture separate to mainstream France, including their own language (Breton), a Celtic language, though it is closer to Welsh than Irish.

The Fall of Icarus, Jacob Peter Gowy, 1630's

Stephen’s recollections of this time are heavily centered around food (which is fun for me because I get to write about French pastries, which I love almost as much as Joyce’s novels). Once again we meet the ineluctable modality of the gustatory, thoughts of which become particularly ineluctable when one is starving and can’t afford food. Hunger weighed heavily on Stephen during those months and still color his memories so long after. Hunger and poverty are traumatic experiences, and they linger in Stephen’s memory in the form of lovely French pastries that he didn’t get to taste, though I wonder if the mou en civet still lingers at the back of his throat despite the passage of time.

Stanislaus said his brother saw the Paris sojourn as a period of “fasting and meditation in the desert” necessary to build an Artist’s character and ability. The “fleshpots of Egypt” remark reinforces this interpretation. It allowed him to know the world was indifferent toward him and his artistic vision - for now. It also proved to him that Europe was the only place for him, the only place where he could have the life he wanted. It was better to be down and out, starving in Paris than to be safe in Ireland while living with the pressures of religion and nationalism. In the pages of Ulysses, Stephen’s return from Paris can be read as a Dedalian blunder. He flew too close to the sun and crashed. Back in Dublin, he is left to pick up the pieces of his ego. I suppose the fall is more Icarian, but it was Dedalus who was left behind once Icarus was gone. And he still had plenty of materials left to rebuild his wings.

Further Reading:

Bowen, Z. (1974). Musical allusions in the works of James Joyce: Early poetry through Ulysses. Albany:State University of New York Press.

Earle, D. (2003). "Green Eyes, I See You. Fang, I Feel": The Symbol of Absinthe in "Ulysses". James Joyce Quarterly,40(4), 691-709. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25477989

Ellmann, R. (1959). James Joyce. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gifford, D., & Seidman, R. J. (1988). Ulysses annotated: Notes for James Joyce's Ulysses. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gilbert, S. (1955). James Joyce’s Ulysses: a study. New York: Vintage Books.

Heininger, J. (1986). Stephen Dedalus in Paris: Tracing the Fall of Icarus in "Ulysses". James Joyce Quarterly,23(4), 435-446. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25476758

Joyce, S. (1958). My brother’s keeper: James Joyce’s early years. New York: The Viking Press.

McCourt, J. (2007). Joyce’s Well of Saints. Joyce Studies Annual. 2007, 109-133. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/1818991/Joyces_Well_of_the_Saints