The Women of Ulysses: Mother Grogan and the Milk Woman

To hear a discussion of this topic, check out the podcast episode here.

Part of an occasional series on the women of Ulysses.

Mother Grogan pops up a couple times throughout Ulysses. She is a reference to an anonymous folk song called Ned Grogan. I couldn’t find a recording of it, so I suppose it’s fallen out of popularity, but if you’re curious about the lyrics, you can find them here. Buck Mulligan invokes her during breakfast in the Martello tower in “Telemachus”:

—When I makes tea I makes tea, as old mother Grogan said. And when I makes water I makes water.

In Harry Blamires’ Bloomsday Book, he says that this line establishes a connection between making tea and urinating, which is a symbol of fertility and creativity.

Haines, the Oxford student fascinated with Ireland’s traditions, is eager to pick up any tidbits of Irish culture or Irish sayings. A modern audience might call Haines’ fawning but shallow love of Ireland cultural appropriation. Mulligan and Stephen, for their part, find Haines fairly ridiculous. We can assume Mulligan is being sarcastic as he suggests:

—That's folk, he said very earnestly, for your book, Haines.

Mulligan’s mockery continues:

—Can you recall, brother, is mother Grogan's tea and water pot spoken of in the Mabinogion or is it in the Upanishads?

—I doubt it, said Stephen gravely.

—Do you now? Buck Mulligan said in the same tone. Your reasons, pray?

—I fancy, Stephen said as he ate, it did not exist in or out of the Mabinogion. Mother Grogan was, one imagines, a kinswoman of Mary Ann.

Mulligan succeeds at both picking on Haines and annoying Stephen. The Mabinogion is a collection of classic Welsh folklore, while the Upanishads are some of the earliest writings on Hindu beliefs. Both the Welsh and the people of India are subjects of the British Empire, so mentioning them is aimed at Haines the Englishman. It’s also a jab at Ireland itself, suggesting that Irish culture doesn’t have a place amongst these classic works. This passage contrasts Mulligan and Stephen’s personalities. Mulligan mocks, subtly, but Stephen speaks “gravely,” not joining in with Mulligans’ joke.

By the way, who is Mary Ann?

She’s also a character from a folk song which Mulligan kindly sings:

—For old Mary Ann

She doesn't care a damn.

But, hising up her petticoats…

The final line, left out by Mulligan, goes “she pisses like a man.” Apparently there are cleaner versions as well, but Mary Ann is a bawdy woman for sure. She and Mother Grogan represent two examples of Irish womanhood and Ireland itself. They also show the lowly position that Irish culture occupies in the minds of Stephen, who admires continental Europe, and Mulligan, who hopes to "hellenism" Ireland, to bring it in line with classical Greece.

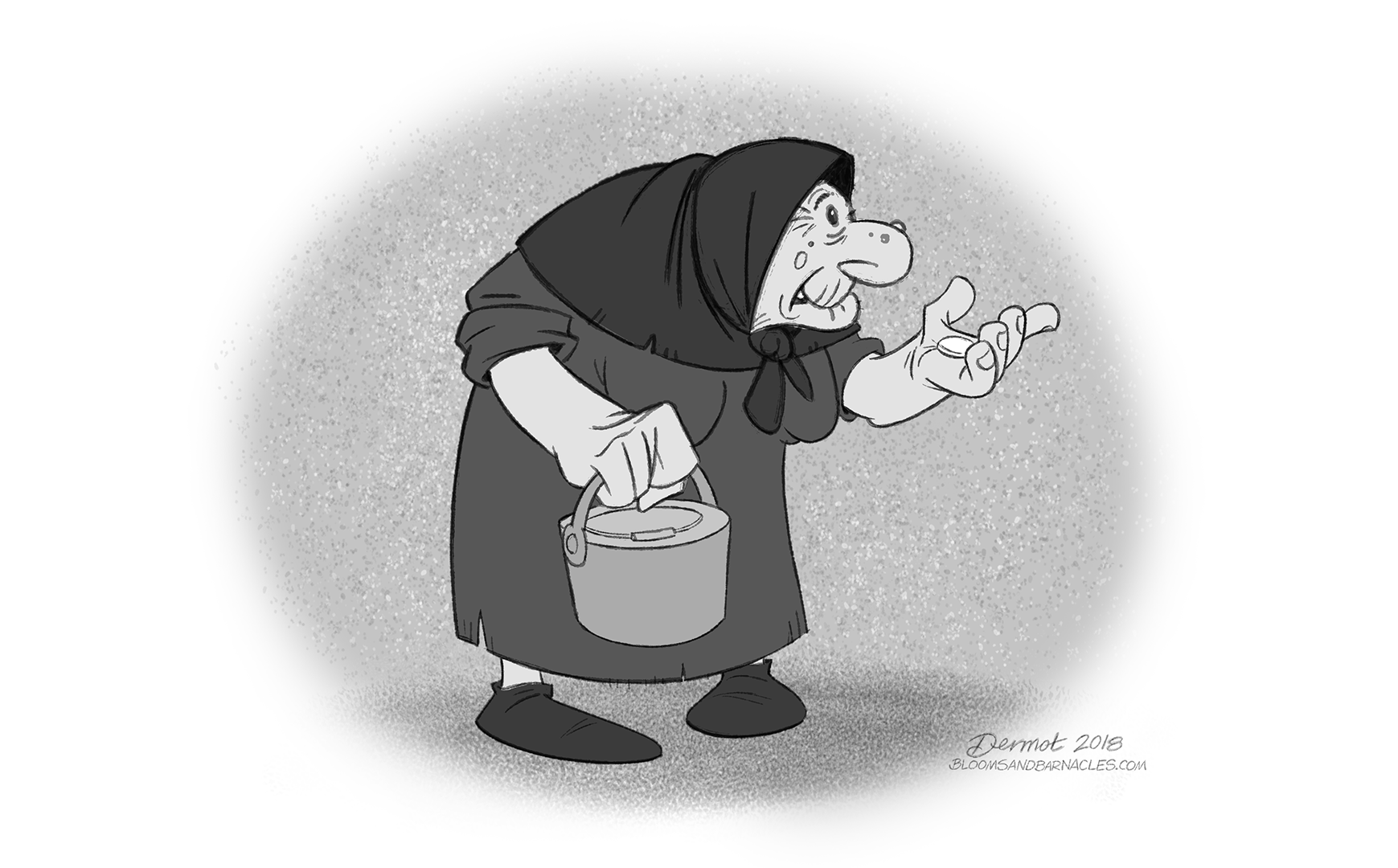

Another example of Irish womanliness steps through the door the tower in the form of an elderly milk woman. Narratively, this is a scene where Stephen buys milk, but his mental appraisal tells us a lot about Stephen’s feelings toward his native Ireland. The old milk woman represents Ireland’s past and backwards-looking traditions.

For example, she is pious:

“—That's a lovely morning, sir, she said. Glory be to God.”

She is unable to nourish, as symbolized by her withered body:

He watched her pour into the measure and thence into the jug rich white milk, not hers. Old shrunken paps.

She is earthy:

Crouching by a patient cow at daybreak in the lush field, a witch on her toadstool, her wrinkled fingers quick at the squirting dugs. They lowed about her whom they knew, dewsilky cattle.

She is subjugated, both by an invading foreigner and the wealthy classes of her native land:

A wandering crone, lowly form of an immortal serving her conqueror [Haines] and her gay betrayer [Mulligan], their common cuckquean, a messenger from the secret morning. To serve or to upbraid, whether he could not tell: but scorned to beg her favour.

She pays no mind to the artist in her midst. Stephen, representing the archetype of “artist,” feels that Ireland is not meeting his creative and intellectual needs:

Stephen listened in scornful silence. She bows her old head to a voice that speaks to her loudly, her bonesetter, her medicineman: me she slights.

She is ignorant of her own culture, though she reveres it. Haines speaks Irish to her, but she doesn’t recognize it. The conqueror, the Englishman instructs her, Ireland personified, that she must learn her native tongue, which was destroyed and banned by the English in the first place:

—He's English, Buck Mulligan said, and he thinks we ought to speak Irish in Ireland.—Sure we ought to, the old woman said, and I'm ashamed I don't speak the language myself. I'm told it's a grand language by them that knows.

Mother Grogan appears again in “Oxen of the Sun,” referenced once more by Buck Mulligan, where she is described as “... the most excellent creature of her sex though 'tis pity she's a trollop): There's a belly that never bore a bastard.” She's virtuous, but not too virtuous. She's got a little Mary Ann in her yet.

And again in “Circe,” where, representing the conservative faction, she twice hurls a boot at Leopold Bloom.

Our milk woman also reappears in “Circe,” as Old Gummy Granny.

Old Gummy Granny in sugarloaf hat appears seated on a toadstool, the deathflower of the potato blight on her breast.

Conservative and nationalistic, she urges Stephen to fight the English soldiers in Nighttown, even though consummate indoor kid Stephen Dedalus attempting to single-handedly take on two burly soldiers can only have a grim ending.

OLD GUMMY GRANNY (Thrusts a dagger towards Stephen's hand.) Remove him, acushla. At 8.35 a.m. you will be in heaven and Ireland will be free.

Stephen recognizes her upon her appearance, and utters the following:

STEPHEN Aha! I know you, grammer! Hamlet, revenge! The old sow that eats her farrow!

“The old sow that eats her farrow” is an important line to remember. It appears in both Ulysses and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which means Joyce found it important enough to bear repeating. In this image, Ireland is the “sow,” the mother pig. “Farrow” means the sow’s young, Stephen and other young Irish people. The conservative elements of Irish culture are holding back progress and crushing the intellectual dreams of a young artist like Stephen. Mother Grogan and Old Gummy Granny may seem quaint and pleasant on the surface to someone with a superficial understanding of Ireland, like Haines. However, for someone like Stephen (and Joyce himself) who has an eye on the wider world, those quaint elements are a prison of sorts. When Haines celebrates these traditions, in Stephen's mind, he is celebrating Ireland's inability to move into the 20th century. A fitting symbol as Joyce left Ireland for continental Europe in the early 1900’s, never to live in the land of his birth again.

Further Reading:

http://web.sas.upenn.edu/ulysses-test/tag/mother-grogan/

Blamires, H. (1985). The Bloomsday Book. New York: University Paperbacks.